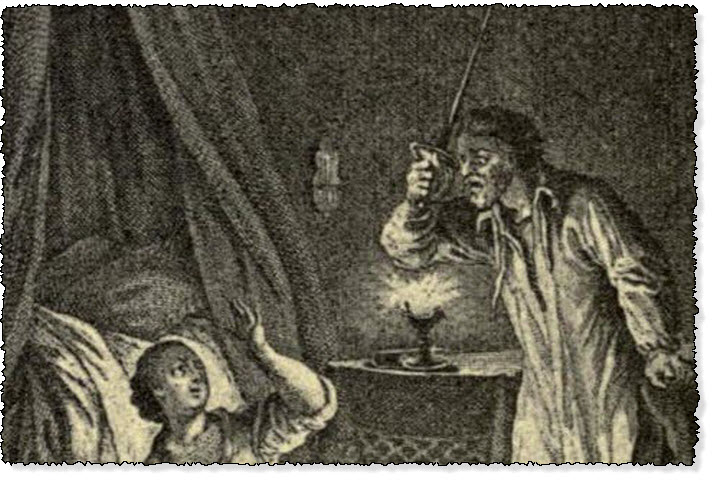

The Muleteer's Servant attacking his Mistress

The Heptameron - Day 1 - Tale 2

Summary of the Second Tale Told on the First Day of the Heptameron

Tale 2 of the Heptameron

In the town of Amboise there was a muleteer in the service of the Queen of Navarre, sister to King Francis, first of that name. She being at Blois, where she had been brought to bed of a son, the aforesaid muleteer went thither to receive his quarterly payment, whilst his wife remained at Amboise in a lodging beyond the bridges.(2)

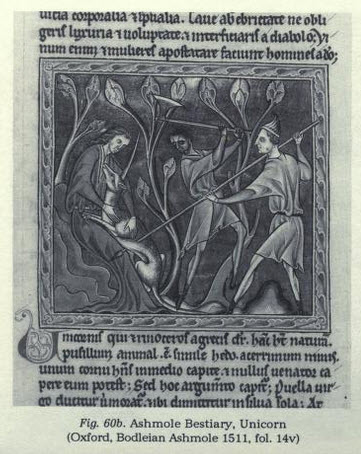

Now it happened that one of her husband's servants had long loved her exceedingly, and one day he could not refrain from speaking of it to her. She, however, being a truly virtuous woman, rebuked him so severely, threatening to have him beaten and dismissed by her husband, that from that time forth he did not venture to speak to her in any such way again or to let his love be seen, but kept the fire hidden within his breast until the day when his master had gone from home and his mistress was at vespers at St. Florentin,(3) the castle church, a long way from the muleteer's house.

Whilst he was alone the fancy took him that he might obtain by force what neither prayer nor service had availed to procure him, and accordingly he broke through a wooden partition which was between the chamber where his mistress slept and his own. The curtains of his master's bed on the one side and of the servant's bed on the other so covered the walls as to hide the opening he had made; and thus his wickedness was not perceived until his mistress was in bed, together with a little girl eleven or twelve years old.

When the poor woman was in her first sleep, the servant, in his shirt and with his naked sword in his hand, came through the opening he had made in the wall into her bed; but as soon as she felt him beside her, she leaped out, addressing to him all such reproaches as a virtuous woman might utter. His love, however, was but bestial, and he would have better understood the language of his mules than her honourable reasonings; indeed, he showed himself even more bestial than the beasts with whom he had long consorted. Finding she ran so quickly round a table that he could not catch her, and that she was strong enough to break away from him twice, he despaired of ravishing her alive, and dealt her a terrible sword-thrust in the loins, thinking that, if fear and force had not brought her to yield, pain would assuredly do so.

The contrary, however, happened, for just as a good soldier, on seeing his own blood, is the more fired to take vengeance on his enemies and win renown, so her chaste heart gathered new strength as she ran fleeing from the hands of the miscreant, saying to him the while all she could think of to bring him to see his guilt. But so filled was he with rage that he paid no heed to her words. He dealt her several more thrusts, to avoid which she continued running as long as her legs could carry her.

When, after great loss of blood, she felt that death was near, she lifted her eyes to heaven, clasped her hands and gave thanks to God, calling Him her strength, her patience, and her virtue, and praying Him to accept her blood which had been shed for the keeping of His commandment and in reverence of His Son, through whom she firmly believed all her sins to be washed away and blotted out from the remembrance of His wrath.

As she was uttering the words, "Lord, receive the soul that has been redeemed by Thy goodness," she fell upon her face to the ground.

Then the miscreant dealt her several thrusts, and when she had lost both power of speech and strength of body, and was no longer able to make any defence, he ravished her.(4)

Having thus satisfied his wicked lust, he fled in haste, and in spite of all pursuit was never seen again.

The little girl, who was in bed with the muleteer's wife, had hidden herself under the bed in her fear; but on seeing that the man was gone, she came to her mistress. Finding her to be without speech or movement, she called to the neighbours from the window for aid; and as they loved and esteemed her mistress as much as any woman that belonged to the town, they came forthwith, bringing surgeons with them. The latter found that she had received twenty-five mortal wounds in her body, and although they did what they could to help her, it was all in vain.

Nevertheless she lingered for an hour longer without speaking, yet making signs with eye and hand to show that she had not lost her understanding. Being asked by a priest in what faith she died, she answered, by signs as plain as any speech, that she placed her hope of salvation in Jesus Christ alone; and so with glad countenance and eyes upraised to heaven her chaste body yielded up its soul to its Creator.

Just as the corpse, having been laid out and shrouded,(5) was placed at the door to await the burial company, the poor husband arrived and beheld his wife's body in front of his house before he had even received tidings of her death. He inquired the cause of this, and found that he had double occasion to grieve; and his grief was indeed so great that it nearly killed him.

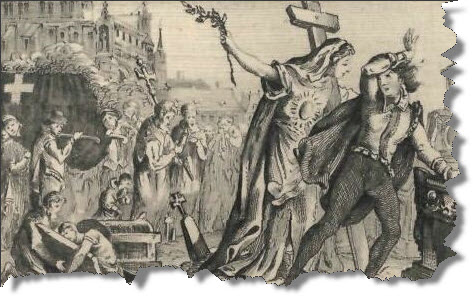

This martyr of chastity was buried in the Church of St. Florentin, and, as was their duty, all the upright women of Amboise failed not to show her every possible honour, deeming themselves fortunate in belonging to a town where so virtuous a woman had been found. And seeing the honour that was shown to the deceased, such women as were wanton and unchaste resolved to amend their lives.

"This, ladies, is a true story, which should incline us more strongly to preserve the fair virtue of chastity. We who are of gentle blood should die of shame on feeling in our hearts that worldly lust to avoid which the poor wife of a muleteer shrank not from so cruel a death. Some esteem themselves virtuous women who have never like this one resisted unto the shedding of blood. It is fitting that we should humble ourselves, for God does not vouchsafe His grace to men because of their birth or riches, but according as it pleases His own good-will. He pays no regard to persons, but chooses according to His purpose; and he whom He chooses He honours with all virtues. And often He chooses the lowly to confound those whom the world exalts and honours; for, as He Himself hath told us, 'Let us not rejoice in our merits, but rather because our names are written in the Book of Life, from which nor death, nor hell, nor sin can blot them out.'" (6)

There was not a lady in the company but had tears of compassion in her eyes for the pitiful and glorious death of the muleteer's wife. Each thought within herself that, should fortune serve her in the same way, she would strive to imitate this poor woman in her martyrdom. Oisille, however, perceiving that time was being lost in praising the dead woman, said to Saffredent—

"Unless you can tell us something that will make the company laugh, I think none of them will forgive me for the fault I have committed in making them weep; wherefore I give you my vote for your telling of the third story."

Saffredent, who would gladly have recounted something agreeable to the company, and above all to one amongst the ladies, said that it was not for him to speak, seeing that there were others older and better instructed than himself, who should of right come first. Nevertheless, since the lot had fallen upon himself, he would rather have done with it at once, for the more numerous the good speakers before him, the worse would his own tale appear.

Footnotes:

- The incidents of this story probably took place at Amboise, subsequent, however, to the month of August 1530, when Margaret was confined of her son John.—L.

- Amboise is on the left bank of the Loire, and there have never been any buildings on the opposite bank. However, the bridge over the river intersects the island of St. Jean, which is covered with houses, and here the muleteer's wife evidently resided.—M.

- The Church of St. Florentin here mentioned must not be confounded with that of the same name near one of the gates of Amboise. Erected in the tenth century by Foulques Nera of Anjou, it was a collegiate church, and was attended by the townsfolk, although it stood within the precincts of the château. For this reason Queen Margaret calls it the castle church.—Ed.

- Brantôme, in his account of Mary Queen of Scots, quotes this story. After mentioning that the headsman remained alone with the Queen's decapitated corpse, he adds: "He then took off her shoes and handled her as he pleased. It is suspected that he treated her in the same way as that miserable muleteer, in the Hundred Stories of the Queen of Navarre, treated the poor woman he killed. Stranger temptations than this come to men. After he (the executioner) had done as he chose, the (Queen's) body was carried into a room adjoining that of her servants." Lalanne's OEuvres de Brantôme, vol. vii. p. 438.—M.

- Common people were then buried in shrouds, not in coffins. —Ed.

- These are not the exact words of Scripture, but a combination of several passages from the Book of Revelation.—Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.