The King Joking upon the Stag's Head being A fitting Decoration

The Heptameron - Day 1 - Tale 3

Summary of the Third Tale Told on the First Day of the Heptameron

Tale 3 of the Heptameron

I have often desired, ladies, to be a sharer in the good fortune of the man whose story I am about to relate to you. You must know that in the time of King Alfonso,(2) whose lust was the sceptre of his kingdom,(3) there lived in the town of Naples a gentleman, so honourable, comely, and pleasant that his perfections induced an old gentleman to give him his daughter in marriage.

She vied with her husband in grace and comeliness, and there was great love between them, until a certain day in Carnival time, when the King went masked from house to house. All strove to give him the best welcome they could, but when he came to this gentleman's house he was entertained better than anywhere else, what with sweetmeats, and singers, and music, and, further, the fairest woman that, to his thinking, he had ever seen. At the end of the feast she sang a song with her husband in so graceful a fashion that she seemed more beautiful than ever.

The King, perceiving so many perfections united in one person, was not over pleased at the gentle harmony between the husband and wife, and deliberated how he might destroy it. The chief difficulty he met with was in the great affection which he observed existed between them, and on this account he hid his passion in his heart as deeply as he could. To relieve it in some measure, he gave many entertainments to the lords and ladies of Naples, and at these the gentleman and his wife were not forgotten. Now, inasmuch as men willingly believe what they desire, it seemed to the King that the glances of this lady gave him fair promise of future happiness, if only she were not restrained by her husband's presence. Accordingly, that he might learn whether his surmise was true, the King intrusted a commission to the husband, and sent him on a journey to Rome for a fortnight or three weeks.

As soon as the gentleman was gone, his wife, who had never before been separated from him, was in great distress; but the King comforted her as often as he was able, with gentle persuasions and presents, so that at last she was not only consoled, but well pleased with her husband's absence. Before the three weeks were over at the end of which he was to be home again, she had come to be so deeply in love with the King that her husband's return was no less displeasing to her than his departure had been. Not wishing to be deprived of the King's society, she agreed with him that whenever her husband went to his country-house she would give him notice of it. He might then visit her in safety, and with such secrecy that her honour, which she regarded more than her conscience, would not suffer.(4)

Having this hope, the lady continued of very cheerful mind, and when her husband arrived she welcomed him so heartily that, even had he been told that the King had sought her in his absence, he would have had no suspicion. In course of time, however, the flame, that is so difficult of concealment, began to show itself, and the husband, having a strong inkling of the truth, kept good watch, by which means he was well-nigh convinced. Nevertheless, as he feared that the man who wronged him would treat him still worse if he appeared to notice it, he resolved to dissemble, holding it better to live in trouble than to risk his life for a woman who had ceased to love him.

In his vexation of spirit, however, he resolved, if he could, to retort upon the King, and knowing that women, especially such as are of lofty and honourable minds, are more moved by resentment than by love, he made bold one day while speaking with the Queen (5) to tell her that it moved his pity to see her so little loved by the King.

The Queen, who had heard of the affection that existed between the King and the gentleman's wife, replied—

"I cannot have both honour and pleasure together. I well know that I have the honour whilst another has the pleasure; and in the same way she who has the pleasure has not the honour that is mine."

Thereupon the gentleman, who understood full well at whom these words were aimed, replied—

"Madam, honour is inborn with you, for your lineage is such that no title, whether of queen or empress, could be an increase of nobility; yet your beauty, grace, and virtue are well deserving of pleasure, and she who robs you of what is yours does a greater wrong to herself than to you, seeing that for a glory which is turned to her shame, she loses as much pleasure as you or any lady in the realm could enjoy. I can truly tell you, madam, that were the King to lay aside his crown, he would not possess any advantage over me in satisfying a lady; nay, I am sure that to content one so worthy as yourself he would indeed be pleased to change his temperament for mine."

The Queen laughed and replied—

"The King may be of a less vigorous temperament than you, yet the love he bears me contents me well, and I prefer it to any other."

"Madam," said the gentleman, "if that were so, I should have no pity for you. I feel sure that you would be well pleased if the like of your own virtuous love were found in the King's heart; but God has withheld this from you in order that, not finding what you desire in your husband, you may not make him your god on earth."

"I confess to you," said the Queen, "that the love I bear him is so great that the like could not be found in any other heart but mine."

"Pardon me, madam," said the gentleman; "you have not fathomed the love of every heart. I will be so bold as to tell you that you are loved by one whose love is so great and measureless that your own is as nothing beside it. The more he perceives that the King's love fails you, the more does his own wax and increase, in such wise that, were it your pleasure, you might be recompensed for all you have lost."

The Queen began to perceive, both from these words and from the gentleman's countenance, that what he said came from the depth of his heart. She remembered also that for a long time he had so zealously sought to do her service that he had fallen into sadness. She had hitherto deemed this to be on account of his wife, but now she was firmly of belief that it was for love of herself. Moreover, the very quality of love, which compels itself to be recognised when it is unfeigned, made her feel certain of what had been hidden from every one. As she looked at the gentleman, who was far more worthy of being loved than her husband, she reflected that he was forsaken by his wife, as she herself was by the King; and then, beset by vexation and jealousy against her husband, as well as moved by the love of the gentleman, she began with sighs and tearful eyes to say—

"Ah me! shall revenge prevail with me where love has been of no avail?"

The gentleman, who understood what these words meant, replied—

"Vengeance, madam, is sweet when in place of slaying an enemy it gives life to a true lover.(6) Methinks it is time that truth should cause you to abandon the foolish love you bear to one who loves you not, and that a just and reasonable love should banish fear, which cannot dwell in a noble and virtuous heart. Come, madam, let us set aside the greatness of your station and consider that, of all men and women in the world, we are the most deceived, betrayed, and bemocked by those whom we have most truly loved. Let us avenge ourselves, madam, not so much to requite them in the way they deserve as to satisfy that love which, for my own part, I cannot continue to endure and live. And I think that, unless your heart be harder than flint or diamond, you cannot but feel some spark from the fires which only increase the more I seek to conceal them. If pity for me, who am dying of love for you, does not move you to love me, at least pity for yourself should do so. You are so perfect that you deserve to win the heart of every honourable man in the world, yet you are contemned and forsaken by him for whose sake you have scorned all others."

On hearing these words the Queen was so greatly moved that, for fear of showing in her countenance the trouble of her mind, she took the gentleman's arm and went forth into a garden that was close to her apartment. There she walked to and fro for a long time without being able to say a word to him. The gentleman saw that she was half won, and when they were at the end of the path, where none could see them, he made a very full declaration of the love which he had so long hidden from her. They found that they were of one mind in the matter, and enacted (7) the vengeance which they were no longer able to forego. Moreover, they there agreed that whenever the husband went into the country, and the King left the castle to visit the wife in the town, the gentleman should always return and come to the castle to see the Queen. Thus, the deceivers being themselves deceived, all four would share in the pleasures that two of them had thought to keep to themselves.

When the agreement had been made, the Queen returned to her apartment and the gentleman to his house, both being so well pleased that they had forgotten all their former troubles. The jealousy they had previously felt at the King's visits to the lady was now changed to desire, so that the gentleman went oftener than usual to his house in the country, which was only half a league distant. As soon as the King was advised of his departure, he never failed to go and see the lady; and the gentleman, when night was come, betook himself to the castle to the Queen, where he did duty as the King's lieutenant, and so secretly that none ever discovered it.

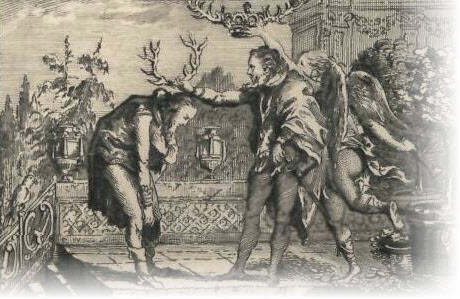

This manner of life lasted for a long time; but as the King was a person of public condition, he could not conceal his love sufficiently well to prevent it from coming at length to the knowledge of every one; and all honourable people felt great pity for the gentleman, though divers malicious youths were wont to deride him by making horns at him behind his back. But he knew of their derision, and it gave him great pleasure, so that he came to think as highly of his horns as of the King's crown.

One day, however, the King and the gentleman's wife, noticing a stag's head that was set up in the gentleman's house, could not refrain in his presence from laughing and saying that the head was suited to the house. Soon afterwards the gentleman, who was no less spirited than the King, caused the following words to be written over the stag's head:—

"Io porto le corna, ciascun lo vede, Ma tal le porta che no lo crede." (8)

When the King came again to the house, he observed these lines newly written, and inquired their meaning of the gentleman, who said—

"If the King's secret be hidden from the subject, it is not fitting that the subject's secret should be revealed to the King. Be content with knowing that those who wear horns do not always have their caps raised from their heads. Some horns are so soft that they never uncap one, and especially are they light to him who thinks he has them not."

The King perceived by these words that the gentleman knew something of his own behaviour, but he never had any suspicion of the love between him and the Queen; for the more pleased the latter was with the life led by her husband, the more did she feign to be distressed by it. And so on either side they lived in this love, until at last old age took them in hand.

"Here, ladies, is a story by which you may be guided, for, as I willingly confess, it shows you that when your husbands give you bucks' horns you can give them stags' horns in return."

"I am quite sure, Saffredent," began Ennasuite laughing, "that if you still love as ardently as you were formerly wont to do, you would submit to horns as big as oak-trees if only you might repay them as you pleased. However, now that your hair is growing grey, it is time to leave your desires in peace."

"Fair lady," said Saffredent, "though I be robbed of hope by the woman I love, and of ardour by old age, yet it lies not in my power to weaken my inclination. Since you have rebuked me for so honourable a desire, I give you my vote for the telling of the fourth tale, that we may see whether you can bring forward some example to refute me."

During this converse one of the ladies fell to laughing heartily, knowing that she who took Saffredent's words to herself was not so loved by him that he would have suffered horns, shame, or wrong for her sake. When Saffredent perceived that the lady who laughed understood him, he was well satisfied and became silent, so that Ennasuite might begin; which she did as follows—

"In order, ladies, that Saffredent and the rest of the company may know that all ladies are not like the Queen he has spoken of, and that all foolhardy and venturesome men do not compass their ends, I will tell you a story in which I will acquaint you with the opinion of a lady who deemed the vexation of failure in love to be harder of endurance than death itself. However, I shall give no names, because the events are so fresh in people's minds that I should fear to offend some who are near of kin."

Footnotes:

- This story is historical. The events occurred at Naples cir. 1450.—L.

- The King spoken of in this story must be Alfonso V., King of Aragon, who was born in 1385, and succeeded his father, Ferdinand the Just, in 1416. He had already made various expeditions to Sardinia and Corsica, when, in 1421, Jane II. of Naples begged of him to assist her in her contest against Louis of Anjou. Alfonso set sail for Italy as requested, but speedily quarrelled with Jane, on account of the manner in which he treated her lover, the Grand Seneschal Caraccioli. Jane, at her death in 1438, bequeathed her crown to René, brother of Louis of Anjou, whose claims Alfonso immediately opposed. Whilst blockading Gaëta he was defeated and captured, but ultimately set at liberty, whereupon he resumed the war. In 1442 he at last secured possession of Naples, and compelled René to withdraw from Italy. From that time Alfonso never returned to Spain, but settling himself in his Italian dominions, assumed the title of King of the Two Sicilies. He obtained the surname of the Magnanimous, from his generous conduct towards some conspirators, a list of whose names he tore to pieces unread, saying, "I will show these noblemen that I have more concern for their lives than they have themselves." The surname of the Learned was afterwards given to him from the circumstance that, like his rival René of Anjou, he personally cultivated letters, and also protected many of the leading learned men of Italy. Alfonso was fond of strolling about the streets of Naples unattended, and one day, when he was cautioned respecting this habit, he replied, "A father who walks abroad in the midst of his children has no cause for fear." Whilst possessed of many remarkable qualities, Alfonso, as Muratori and other writers have shown, was of an extremely licentious disposition. That he had no belief in conjugal fidelity is evidenced by his saying that "to ensure domestic happiness the husband should be deaf and the wife blind." He himself had several mistresses, and lived at variance with his wife, respecting whom some particulars are given in a note on page 69. He died in 1458, at the age of seventy-four, bequeathing his Italian possessions to Ferdinand, Duke of Calabria, his natural son by a Spanish beauty named Margaret de Hijar. It may be added that Brantôme makes a passing allusion to this tale of the Heptameron in his Vies des Dames Galantes (Disc, i.), styling it "a very fine one."—L. and Ed.

- Meaning that he employed his sovereign authority for the accomplishment of his amorous desires.—M.

- The edition of 1558 is here followed, the MSS. being rather obscure.—M.

- This was Mary (daughter of Henry III. of Castile), who was married to King Alfonso at Valencia on June 29, 1415. Juan de Mariana, the Spanish historian, records that the ceremony was celebrated with signal pomp by the schismatical Pope Benedict XIII. The bride brought her husband a dowry of 200,000 ducats, and also various territorial possessions. The marriage, however, was not a happy one, on account of Alfonso's licentious disposition, and the Queen is said to have strangled one of his mistresses, Margaret de Hijar, in a fit of jealousy. Alfonso, to escape from his wife's interference, turned his attention to foreign expeditions. According to the authors of L'Art de Vérifier les Dates, Queen Mary never once set foot in Italy, and this statement is borne out by Mariana, who shows that whilst Alfonso was reigning in Naples his wife governed the kingdom of Aragon, making war and signing truces and treaties of peace with Castile. In the Heptameron, therefore, Margaret departs from historical accuracy when she represents the Queen as residing at Naples with her husband. Moreover, judging by the date of Mary's marriage, she could no longer have been young when Alfonso secured the Neapolitan throne. It is to be presumed that the Queen of Navarre designedly changed the date of her story, and that the incidents referred to really occurred in Spain prior to Alfonso's departure for Italy. There is no mention of Mary in her husband's will, a remarkable document which is still extant. A letter written to her by Pope Calixtus II. shows that late in life the King was desirous of repudiating her to marry an Italian mistress named Lucretia Alania. The latter repaired to Rome to negotiate the affair, but the Pope refused to treat with her, and wrote to Mary saying that she must be prudent, but that he would not dissolve the marriage, lest God should punish him for participating in so great a crime. Mary died a few months after her husband in 1458, and was buried in a convent at Valencia.—L. and Ed.

- The above sentence being omitted in the MS. followed in this edition, it has been supplied from MS. No. 1520 in the Bibliothèque Nationale.—L.

- This expression has allusion to the mysteries or religious plays so frequently performed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Mystery of Vengeance, which depicted the misfortunes which fell upon those who had taken part in the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, such as Pontius Pilate, &c, and ended by the capture and destruction of Jerusalem, properly came after the Mysteries of the Passion and the Resurrection.—L.

-

"All men may see the horns I've got, But one wears horns

and knows it not."

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.