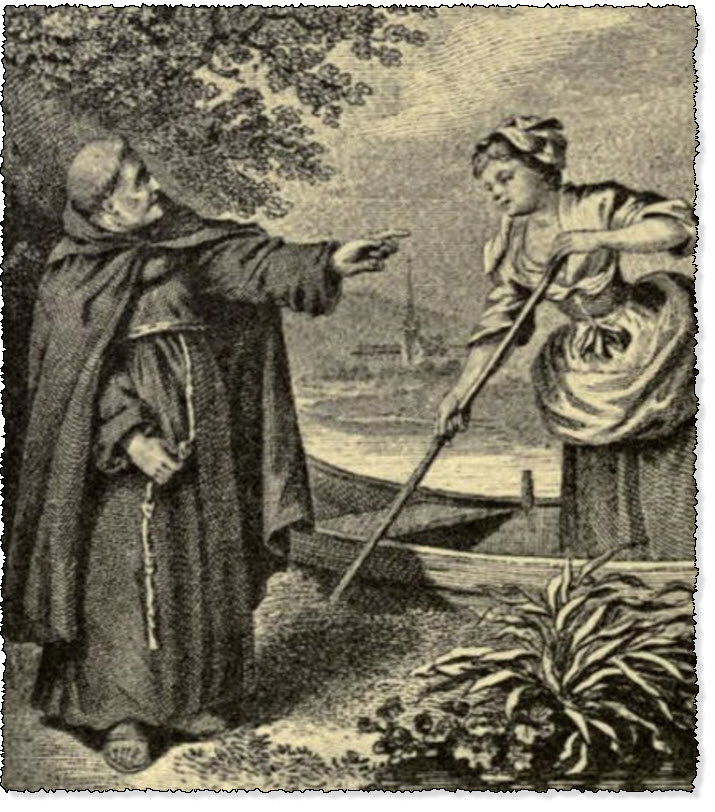

The Boatwoman of Coulon outwitting the Friars

The Heptameron - Day 1 - Tale 5

Summary of the Fifth Tale Told on the First Day of the Heptameron

Tale 5 of the Heptameron

At the haven of Coulon,(1) near Nyort, there lived a boatwoman who, day or night, did nothing but convey passengers across the ferry.

Now it chanced that two Grey Friars from Nyort were crossing the river alone with her, and as the passage is one of the longest in France, they began to make love to her, that she might not feel dull by the way. She returned them the answer that was due; but they, being neither fatigued by their journeying, nor cooled by the water, nor put to shame by her refusal, determined to take her by force, and, if she clamoured, to throw her into the river. She, however, was as virtuous and clever as they were gross and wicked, and said to them—

"I am not so ill-disposed as I seem to be, but I pray you grant me two requests. You shall then see that I am more ready to give than you are to ask."

The friars swore to her by their good St. Francis that she could ask nothing that they would not grant in order to have what they desired of her.

"First of all," she said, "I require you both to promise on oath that you will inform no man living of this matter." This they promised right willingly.

"Then," she continued, "I would have you take your pleasure with me one after the other, for it would be too great a shame for me to have to do with one in presence of the other. Consider which of you will have me first."

They deemed her request a very reasonable one, and the younger friar yielded the first place to the elder. Then, as they were drawing near a little island, she said to the younger one—

"Good father, say your prayers here until I have taken your companion to another island. Then, if he praises me when he comes back, we will leave him here, and go away in turn together."

The younger friar leapt out on to the island to await the return of his comrade, whom the boat-woman took away with her to another island. When they had reached the bank she said to him, pretending the while to fasten her boat to a tree—

"Look, my friend, and see where we can place ourselves."

The good father stepped on to the island to seek for a convenient spot, but no sooner did she see him on land than she struck her foot against the tree and went off with her boat into the open stream, leaving both the good fathers to their deserts, and crying out to them as loudly as she could—

"Wait now, sirs, till the angel of God comes to console you; for you shall have nought that could please you from me to-day."

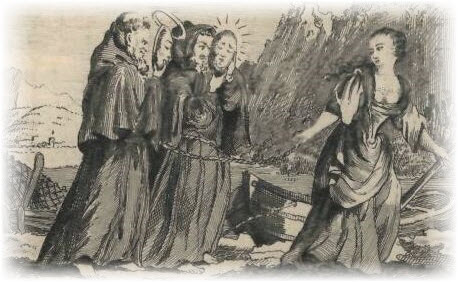

The two poor monks, perceiving that they had been deceived, knelt down at the water's edge and besought her not to put them to such shame; and they promised that they would ask nothing of her if she would of her goodness take them to the haven. But, still rowing away, she said to them—

"I should be doubly foolish if, after escaping out of your hands, I were to put myself into them again."

When she had come to the village, she went to call her husband and the ministers of justice that they might go and take these fierce wolves, from whose fangs she had by the grace of God escaped. They set out accompanied by many people, for there was no one, big or little, but wished to share in the pleasure of this chase.

When the poor brethren saw such a large company approaching, they hid themselves each in his island, even as Adam did when he perceived his nakedness in the presence of God.(2) Shame set their sin clearly before them, and the fear of punishment made them tremble so that they were half dead. Nevertheless, they were taken prisoners amid the mockings and hootings of men and women.

Some said, "These good fathers preach chastity to us and then rob our wives of theirs." (3)

Others said, "They are like unto whited sepulchres, which indeed appear beautiful outward, but are within full of dead men's bones and uncleanness." (4) Then another voice cried, "By their fruits shall ye know what manner of trees they are." (5)

You may be sure that all the passages in the Gospel condemning hypocrites were brought forward against the unhappy prisoners, who were, however, rescued and delivered by their Warden,(6) who came in all haste to claim them, assuring the ministers of justice that he would visit them with a greater punishment than laymen would venture to inflict, and that they should make reparation by saying as many masses and prayers as might be required. The judge granted the Warden's request and gave the prisoners up to him; and the Warden, who was an upright man, so dealt with them that they never afterwards crossed a river without making the sign of the cross and recommending themselves to God.(7)

"I pray you, ladies, consider, since this poor boatwoman had the wit to deceive two such evil men, what should be done by those who have read of and witnessed so many fair examples, and who have had the goodness of virtuous ladies ever before their eyes? Indeed, the virtue of well-bred women is not so much to be called virtue as habit. It is in the women who know nothing, who hear scarcely two good sermons during the whole year, who have no leisure to think of aught save the gaining of their miserable livelihood, and who nevertheless jealously guard their chastity, hard-pressed as they may be (8)—it is in such women as these that one discovers the virtue that is natural to the heart. Where man's wit and might are smallest, there the Spirit of God performs the greatest work. And unhappy indeed is the lady who keeps not close ward over the treasure which brings her so much honour if it be well guarded, and so much shame if it be neglected."

"It seems to me, Geburon," said Longarine, "that there is no great virtue in refusing a Grey Friar, and that it would rather be impossible to love one."

"Longarine," replied Geburon, "they who are not accustomed to such lovers as yours do by no means despise the Grey Friars, for the latter are as handsome and as strong as we are, and they are readier and fresher also, for we are worn-out with our service. Moreover, they talk like angels and are as importunate as the devil, so that such women as have never seen other robes than their coarse drugget ones,(9) are truly virtuous when they escape out of their hands."

"In faith," said Nomerfide, in a loud voice, "you may say what you like, but I would rather be thrown into the river than lie with a Grey Friar.''

"So you can swim well?" said Oisille, laughing.

Nomerfide took this question in bad part, for she thought that she was esteemed by Oisille less highly than she desired. Accordingly she answered in anger—

"There are some who have refused more agreeable men than Grey Friars without blowing a trumpet about it."

Oisille laughed to see her so wrathful, and said to her—

"Still less do they beat a drum about what they have done and granted."

"I see," said Geburon, "that Nomerfide wishes to speak. I therefore give her my vote that she may relieve her heart in telling us some excellent story."

"What has just been said," replied Nomerfide, "touches me so little that it affords me neither pleasure nor pain. However, since I have your vote, I pray you listen to me whilst I show that, although one woman used cunning for a good purpose, others have been crafty for evil's sake. Since we have sworn to tell the truth I will not hide it, for just as the boatwoman's virtue brings no honour to other women unless they follow her example, so the vice of another cannot disgrace her. Wherefore, listen."

Footnotes:

- The village of Coulon, in Poitou (department of the Deux- Sèvres), lies within seven miles of Niort, on the Niortaise Sevre, which at this point is extremely wide.—L.

- See Genesis iii. 8-10.

- The editions of 1558 and 1560 here contain this additional phrase: "They do not dare to touch money with bare hands, and yet they willingly finger the thighs of our wives, which are more dangerous."—L.

- St. Matthew xxiii. 27.

- "For every tree is known by his own fruit."—St. Luke vi. 45.

- The Father Superior of the Grey Friars was called the Warden.—B.J.

- Henry Etienne quotes this story in his Apologie pour Hérodote, and praises the Queen for thus denouncing the evil practices of the friars.—F.

- Boaistuau's edition of 1558 here contains the following interpolation: "As should be done by those who, having their lives provided for, have no occupation save that of studying Holy Writ, listening to sermons and preaching, and exerting themselves to act virtuously in all things."—L.

- Meaning who have never seen gallants in gay apparel.—Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.