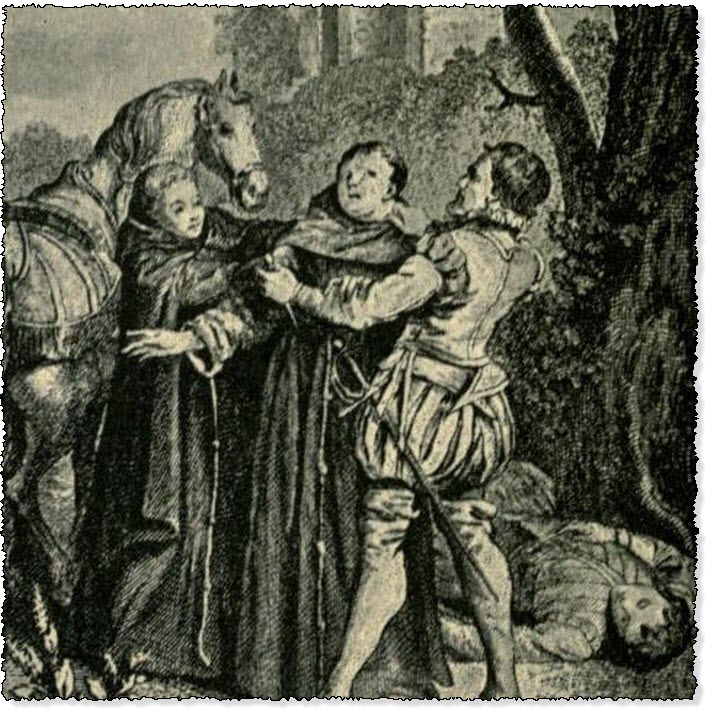

the Wicked Friar Captured

The Heptameron - Day 4, Tale 31- the Wicked Friar Captured

TALE XXXI.

A monastery of Grey Friars was burned down, with the monks that were in it, as a perpetual memorial of the cruelty practised by one among them that was in love with a lady.

In the lands subject to the Emperor Maximilian of Austria (1) there was a monastery of Grey Friars that was held in high repute, and nigh to it stood the house of a gentleman who was so kindly disposed to these monks that he could withhold nothing from them, in order to share in the benefits of their fastings and disciplines. Among the rest there was a tall and handsome friar whom the said gentleman had taken to be his confessor, and who had as much authority in the gentleman's house as the gentleman himself. This friar, seeing that the gentleman's wife was as beautiful and prudent as it was possible to be, fell so deeply in love with her that he lost all appetite for both food and drink, and all natural reason as well. One day, thinking to work his end, he went all alone to the house, and not finding the gentleman within, asked the lady whither he was gone. She replied that he was gone to an estate where he proposed remaining during two or three days, but that if the friar had business with him, she would despatch a man expressly to him. The friar said no to this, and began to walk to and fro in the house like one with a weighty matter in his mind.

1 Maximilian I., grandfather of Charles V. and Ferdinand I., and Emperor of Germany from 1494 to 1519.—Ed.

When he had left the room, the lady said to one of her women (and there were but two) "Go after the good father and find out what he wants, for I judge by his countenance that he is displeased."

The serving-woman went to the courtyard and asked the friar whether he desired aught, whereat he answered that he did, and, drawing her into a corner, he took a dagger which he carried in his sleeve, and thrust it into her throat. Just after he had done this, there came into the courtyard a mounted servant who had been gone to receive the rent of a farm. As soon as he had dismounted he saluted the friar, who embraced him, and while doing so thrust the dagger into the back part of his neck. And thereupon he closed the castle gate.

The lady, finding that her serving-woman did not return, was astonished that she should remain so long with the friar, and said to the other—

"Go and see why your fellow-servant does not come back."

The woman went, and as soon as the good father saw her, he drew her aside into a corner and did to her as he had done to her companion. Then, finding himself alone in the house, he came to the lady, and told her that he had long been in love with her, and that the hour was now come when she must yield him obedience.

The lady, who had never suspected aught of this, replied—

"I am sure, father, that were I so evilly inclined, you would be the first to cast a stone at me."

"Come out into the courtyard," returned the monk, "and you will see what I have done."

When she beheld the two women and the man lying dead, she was so terrified that she stood like a statue, without uttering a word. The villain, who did not seek merely an hour's delight, would not take her by force, but forthwith said to her—

"Mistress, be not afraid; you are in the hands of him who, of all living men, loves you the most."

So saying, he took off his long robe, beneath which he wore a shorter one, which he gave to the lady, telling her that if she did not take it, she should be numbered with those whom she saw lying lifeless before her eyes.

More dead than alive already, the lady resolved to feign obedience, both to save her life, and to gain time, as she hoped, for her husband's return. At the command of the friar, she set herself to put off her head-dress as slowly as she was able; and when this was done, the friar, heedless of the beauty of her hair, quickly cut it off. Then he caused her to take off all her clothes except her chemise, and dressed her in the smaller robe he had worn, he himself resuming the other, which he was wont to wear; then he departed thence with all imaginable speed, taking with him the little friar he had coveted so long.

Heptameron Story 31

But God, who pities the innocent in affliction, beheld the tears of this unhappy lady, and it so happened that her husband, having arranged matters more speedily than he had expected, was now returning home by the same road by which she herself was departing. However, when the friar perceived him in the distance, he said to the lady—

"I see your husband coming this way. I know that if you look at him he will try to take you out of my hands. Go, then, before me, and turn not your head in his direction; for, if you make the faintest sign, my dagger will be in your throat before he can deliver you."

As he was speaking, the gentleman came up, and asked him whence he was coming.

"From your house," replied the other, "where I left my lady in good health, and waiting for you."

The gentleman passed on without observing his wife, but a servant who was with him, and who had always been wont to foregather with one of the friar's comrades named Brother John, began to call to his mistress, thinking, indeed, that she was this Brother John. The poor woman, who durst not turn her eyes in the direction of her husband, answered not a word. The servant, however, wishing to see her face, crossed the road, and the lady, still without making any reply, signed to him with her eyes, which were full of tears.

The servant then went after his master and said—"Sir, as I crossed the road I took note of the friar's companion. He is not Brother John, but is very like my lady, your wife, and gave me a pitiful look with eyes full of tears."

The gentleman replied that he was dreaming, and paid no heed to him; but the servant persisted, entreating his master to allow him to go back, whilst he himself waited on the road, to see if matters were as he thought. The gentleman gave him leave, and waited to see what news he would bring him. When the friar heard the servant calling out to Brother John, he suspected that the lady had been recognised, and with a great, iron-bound stick that he carried, he dealt the servant so hard a blow in the side that he knocked him off his horse. Then, leaping upon his body, he cut his throat.

The gentleman, seeing his servant fall in the distance, thought that he had met with an accident, and hastened back to assist him. As soon as the friar saw him, he struck him also with the iron-bound stick, just as he had struck the servant, and, flinging him to the ground, threw himself upon him. But the gentleman being strong and powerful, hugged the friar so closely that he was unable to do any mischief, and was forced to let his dagger fall. The lady picked it up, and, giving it to her husband, held the friar with all her strength by the hood. Then her husband dealt the friar several blows with the dagger, so that at last he cried for mercy and confessed his wickedness. The gentleman was not minded to kill him, but begged his wife to go home and fetch their people and a cart, in which to carry the friar away. This she did, throwing off her robe, and running as far as her house in nothing but her shift, with her cropped hair.

The gentleman's men forthwith hastened to assist their master to bring away the wolf that he had captured. And they found this wolf in the road, on the ground, where he was seized and bound, and taken to the house of the gentleman, who afterwards had him brought before the Emperor's Court in Flanders, when he confessed his evil deeds.

And by his confession and by proofs procured by commissioners on the spot, it was found that a great number of gentlewomen and handsome wenches had been brought into the monastery in the same fashion as the friar of my story had sought to carry off this lady; and he would have succeeded but for the mercy of Our Lord, who ever assists those that put their trust in Him. And the said monastery was stripped of its spoils and of the handsome maidens that were found within it, and the monks were shut up in the building and burned with it, as an everlasting memorial of this crime, by which we see that there is nothing more dangerous than love when it is founded upon vice, just as there is nothing more gentle or praiseworthy when it dwells in a virtuous heart. (2)

2 Queen Margaret states (ante, p. 5) that this tale was told by M. de St.-Vincent, ambassador of Charles V., and seems to imply that the incident recorded in it was one of recent occurrence. The same story may be found, however, in most of the collections of early fabliaux. See OEuvres de Rutebeuf, vol. i. p. 260 (Frère Denise), Legrand d'Aussy's Fabliaux, vol. iv. p. 383, and the Recueil complet des Fabliaux, Paris, 1878, vol. iii. p. 253. There is also some similarity between this tale and No. LX. of the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles. Estienne quotes it in his Apologie pour Hérodote, L'Estoile in his Journal du règne de Henri III. (anno 1577), Malespini uses it in his Ducento Novelle (No. 75), and it suggested to Lafontaine his Cordeliers de Catalogne.—L. and M.

"I am very sorry, ladies, that truth does not provide us with stories as much to the credit of the Grey Friars as it does to the contrary. It would be a great pleasure to me, by reason of the love that I bear their Order, if I knew of one in which I could really praise them; but we have vowed so solemnly to speak the truth that, after hearing it from such as are well worthy of belief, I cannot but make it known to you. Nevertheless, I promise you that, whenever the monks shall accomplish a memorable and glorious deed, I will be at greater pains to exalt it than I have been in relating the present truthful history."

"In good faith, Geburon," said Oisille, "that was a love which might well have been called cruelty."

"I am astonished," said Simontault, "that he was patient enough not to take her by force when he saw her in her shift, and in a place where he might have mastered her."

"He was not an epicure, but a glutton," said Saffredent. "He wanted to have his fill of her every day, and so was not minded to amuse himself with a mere taste."

"That was not the reason," said Parlamente. "Understand that a lustful man is always timorous, and the fear that he had of being surprised and robbed of his prey led him, wolf-like, to carry off his lamb that he might devour it at his ease."

"For all that," said Dagoucin, "I cannot believe that he loved her, or that the virtuous god of love could dwell in so base a heart."

"Be that as it may," said Oisille, "he was well punished, and I pray God that like attempts may meet with the same chastisement. But to whom will you give your vote?"

"To you, madam," replied Geburon; "you will, I know, not fail to tell us a good story."

"Since it is my turn," said Oisille, "I will relate to you one that is indeed excellent, seeing that the adventure befel in my own day, and before the eyes of him who told it to me. You are, I am sure, aware that death ends all our woes, and this being so, it may be termed our happiness and tranquil rest. It is, therefore, a misfortune if a man desires death and cannot obtain it, and so the most grievous punishment that can be given to a wrongdoer is not death, but a continual torment, great enough to render death desirable, but withal too slight to bring it nearer. And this was how a husband used his wife, as you shall hear."

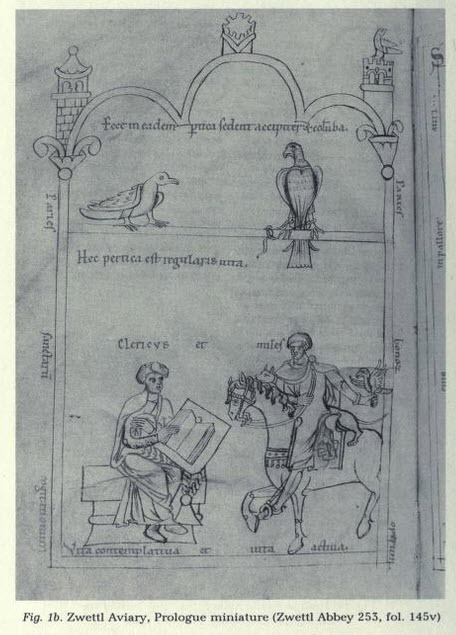

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.