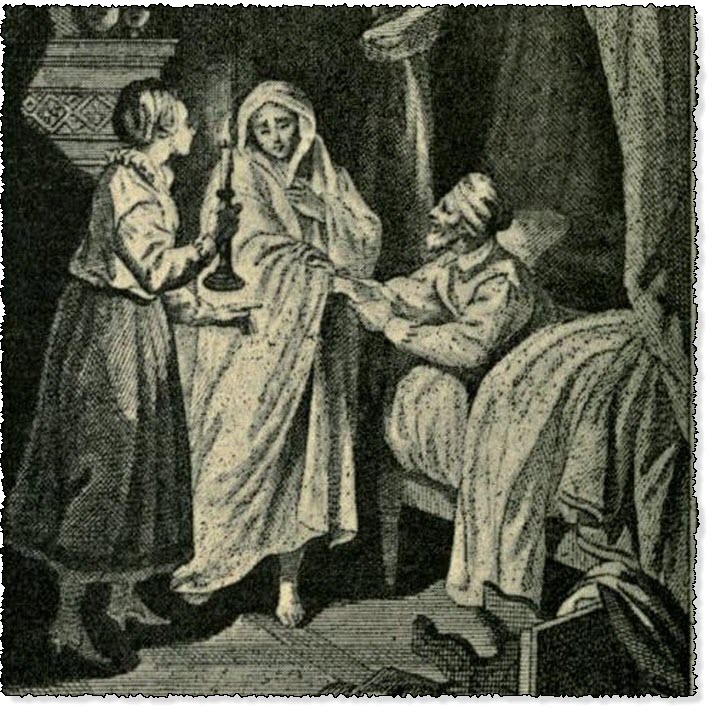

The Heptameron - the Lord of Grignaulx Catching The Pretended Ghost

TALE XXXIX.

The Lord of Grignaulx freed his house from a ghost which had so tormented his wife that for the space of two years she had dwelt elsewhere.

A certain Lord of Grignaulx (1) who was gentleman of honour to the Queen of France, Anne, Duchess of Brittany, on returning to his house whence he had been absent during more than two years, found his wife at another estate, near by, and when he inquired the reason of this, she told him that a ghost was wont to haunt the house, and tormented them so much that none could dwell there. (2) Monsieur de Grig-naulx, who had no belief in such absurdities, replied that were it the devil himself he was not afraid of him, and so brought his wife home again.

At night he caused many candles to be lighted that he might see the ghost more clearly, and, after watching for a long time without hearing anything, he fell asleep; but immediately afterwards he was awaked by a buffet upon the cheek, and heard a voice crying, "Brenigne, Brenigne," which had been the name of his grandmother. (3) Then he called to the serving-woman, who lay near them, (4) to light the candle, for all were now extinguished, but she durst not rise. And at the same time the Lord of Grig-naulx felt the covering pulled from off him, and heard a great noise of tables, trestles and stools falling about the room; and this lasted until morning. However, the Lord of Grignaulx was more displeased at losing his rest than afraid of the ghost, for indeed he never believed it to be any such thing.

1 This is John de Talleyrand, knight, lord of Grignols and Fouquerolles, Prince of Chalais, Viscount of Fronsac, mayor and captain of Bordeaux, chamberlain of Charles VIII., first majordomo and gentleman of honour in turn to two French Queens, Anne of Brittany and Mary of England. His wife was Margaret de la Tour, daughter of Anne de la Tour, Viscount of Turenne, and Mary de Beaufort. She bore him several children. It was John de Talleyrand who warned Louise of Savoy that her son Francis, then Count of Angoulême, was paying court to the young Queen, Mary of England, wife to Louis XII. Apprehensive lest this intrigue should destroy her son's prospects, Louise prevailed on him to relinquish it (Brantôme's Dames Illustres).—L. 4 89 2 The house haunted by the ghost would probably be Talleyrand's château at Grignols, in the department of the Gironde. His lordship of Fouquerolles was only a few miles distant, in the Dordogne, and this would be the estate to which his wife had retired.—Ed. 3 Talleyrand's grandmother on the paternal side was Mary of Brabant; the reference may be to his maternal grandmother, whose Christian name was possibly "Bénigne." On the other hand, Boaistuau gives the name as Revigne, and among the old French noblesse were the Revigné and Revigny families.— Ed. 4 See ante, note 2 to Tale XXXVII.

On the following night he resolved to capture this ghost, and so, when he had been in bed a little while, he pretended to snore very loudly, and placed his open hand close to his face. Whilst he was in this wise waiting for the ghost, he felt that something was coming near him, and accordingly snored yet louder than before, whereat the ghost was so encouraged as to deal him a mighty blow. Forthwith, the Lord of Grignaulx caught the ghost's hand as it rested on his face, and cried out to his wife—

"I have the ghost!"

His wife immediately rose up and lit the candle, and found that it was the serving-woman who slept in their room; and she, throwing herself upon her knees, entreated forgiveness and promised to confess the truth. This was, that she had long loved a serving-man of the house, and had taken this fine mystery in hand in order to drive both master and mistress away, so that she and her lover, having sole charge of the house, might be able to make good cheer as they were wont to do when alone. My Lord of Grignaulx, who was a somewhat harsh man, commanded that they should be soundly beaten so as to prevent them from ever forgetting the ghost, and this having been done, they were driven away. In this fashion was the house freed from the plaguy ghosts who for two years long had played their pranks in it. (5)

5 Talleyrand, who passes for having been the last of the "Rois des Ribauds" (see the Bibliophile Jacob's historical novel of that title), was, like his descendant the great diplomatist, a man of subtle and caustic humour. Brantôme, in his article on Anne of Brittany in Les Dames Illustres, repeatedly refers to him, and relates that on an occasion when the Queen wished to say a few words in Spanish to the Emperor's ambassador—there was a project of marrying her daughter Claude to Charles V.—she applied to Grignols to teach her a sentence or two of the Castilian language. He, however, taught her some dirty expression, but was careful to warn Louis XII., who laughed at it, telling his wife on no account to use the Spanish words she had learnt. On discovering the truth, Anne was so greatly vexed, that Grignols was obliged to withdraw from Court for some time, and only with difficulty obtained the Queen's forgiveness.— L. and Ed.

"It is wonderful, ladies, to think of the effects wrought by the mighty god of Love. He causes women to put aside all fear, and teaches them to give every sort of trouble to man in order to work their own ends. But if the purpose of the serving-woman calls for blame, the sound sense of the master is no less worthy of praise. He knew that when the spirit departs, it returns no more." (6)

6 "A wind that passeth away, and cometh not again."—Psalm lxxviii. 39.—M.

"In sooth," said Geburon, "love showed little favour to the man and the maid, but I agree that the sound sense of the master was of great advantage to him."

Heptameron Story 39

"Nevertheless," said Ennasuite, "the maid through her cunning lived for a long time at her ease."

"'Tis but a sorry ease," said Oisille, "that is founded upon sin and that ends in shame and chastisement."

"That is true, madam," said Ennasuite, "but many persons reap pain and sorrow by living righteously, and lacking wit enough to procure themselves in all their lives as much pleasure as these two."

"It is nevertheless my opinion," said Oisille, "that there can be no perfect pleasure unless the conscience be at rest."

"Nay," said Simontault, "the Italian maintains that the greater the sin the greater the pleasure." (7)

7 This may be a reference to Boccaccio or Castiglione, but the expression is of a proverbial character in many languages.—Ed.

"In very truth," said Oisille, "he who invented such a saying must be the devil himself. Let us therefore say no more of him, but see to whom Saffredent will give his vote."

"To whom?" said he. "Only Parlamente now remains; but if there were a hundred others, she should still receive my vote, as being the one from whom we shall certainly learn something."

"Well, since I am to end the day," said Parlamente, "and since I promised yesterday to tell you why Rolandine's father built the castle in which he kept her so long a prisoner, I will now relate it to you."

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.