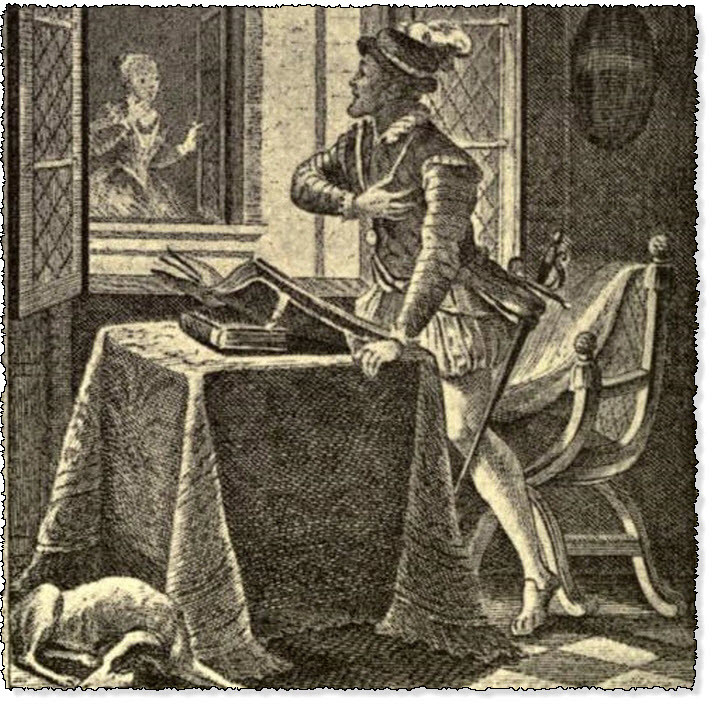

Rolandine Conversing With Her Husband

The Heptameron - Day 3, Tale 21 - Rolandine Conversing With Her Husband

TALE XXI.

Having remained unmarried until she was thirty years of age, Rolandine, recognising her father's neglect and her mistress's disfavour, fell so deeply in love with a bastard gentleman that she promised him marriage; and this being told to her father he treated her with all the harshness imaginable, in order to make her consent to the dissolving of the marriage; but she continued steadfast in her love until she had received certain tidings of the Bastard's death, when she was wedded to a gentleman who bore the same name and arms as did her own family.

There was in France a Queen (1) who brought up in her household several maidens belonging to good and noble houses. Among others there was one called Rolandine, (2) who was near akin to the Queen; but the latter, being for some reason unfriendly with the maiden's father, showed her no great kindness.

Now, although this maiden was not one of the fairest—nor yet indeed was she of the ugliest—she was nevertheless so discreet and virtuous that many persons of great consequence sought her in marriage. They had, however, but a cold reply; for the father (3) was so fond of his money that he gave no thought to his daughter's welfare, while her mistress, as I have said, bore her but little favour, so that she was sought by none who desired to be advanced in the Queen's good graces.

1 This is evidently Anne of Brittany, elder daughter of Duke Francis II. and wife in turn of Charles VIII. and Louis XII. Brantôme says: "She was the first to form that great Court of ladies which we have seen since her time until now; she always had a very great suite of ladies and maids, and never refused fresh ones; far from it, indeed, for she would inquire of the noblemen at Court if they had daughters, and would ask that they might be sent to her."—Lalanne's OEuvres de Brantôme, vol. vii. p. 314—L. 2 This by the consent of all the commentators is Anne de Rohan, elder daughter of John II. Viscount de Rohan, Count of Porhoët, Léon and La Garnache, by Mary of Brittany, daughter of Duke Francis I. The date of Anne de Rohan's birth is not exactly known, but she is said to have been about thirty years of age at the time of the tale, though the incidents related extend over a somewhat lengthy period. However, we know that Anne was ultimately married to Peter de Rohan in 1517, when, according to her marriage contract, she was over thirty-six years old (Les Preuves de Histoire ecclésiastique et civile de Bretagne, 1756, vol. v. col. 940). From this we may assume that she was thirty in or about 1510. The historical incidents alluded to in the tale would, however, appear to have occurred (as will be shown by subsequent notes) between 1507 and 1509, and we are of opinion that the Queen of Navarre has made her heroine rather older than she really was, and that the story indeed begins in or about 1505, when Rolandine can have been little more than five or six and twenty.—Ed. 3 See notes to Tale XL. (vol. iv).

Thus, owing to her father's neglect and her mistress's disdain, the poor maiden continued unmarried for a long while; and this at last made her sad at heart, not so much because she longed to be married as because she was ashamed at not being so, wherefore she forsook the vanities and pomps of the Court and gave herself up wholly to the worship of God. Her sole delight consisted in prayer or needlework, and thus in retirement she passed her youthful years, living in the most virtuous and holy manner imaginable.

Heptameron Story 21

Now, when she was approaching her thirtieth year, there was at Court a gentleman who was a Bastard of a high and noble house; (4) he was one of the pleasantest comrades and most worshipful men of his day, but he was wholly without fortune, and possessed of such scant comeliness that no lady would have chosen him for her lover.

4 One cannot absolutely identify this personage; but judging by what is said of him in the story—that he came of a great house, that he was very brave but poor, neither rich enough to marry Rolandine nor handsome enough to be made a lover of, and that a lady, who was a near relative of his, came to the Court after his intrigue had been going on for a couple of years—he would certainly appear to be John, Bastard of Angoulôme, a natural son of Count John the Good, and consequently half-brother to Charles of Angoulôme ( who married Louise of Savoy) and uncle to Francis I. and Queen Margaret. In Père Anselme's Histoire Généalogique de la Maison de France, vol. i. p. 210 B. there is a record of the letters of legitimisation granted to the Bastard of Angoulême at his father's request in June 1458, and M. Paul Lacroix points out that if Rolandine's secret marriage to him took place in or about 1508, he would then have been about fifty years old, hardly the age for a lover. The Bastard is, however, alluded to in the tale as a man of mature years, and as at the outset of the intrigue (1505) he would have been but forty-seven, we incline with M. de Lincy to the belief that he is the hero of it.—Eu.

Thus this poor gentleman had continued unmated, and as one unfortunate often seeks out another, he addressed himself to Rolandine, whose fortune, temper and condition were like his own. And while they were engaged in mutually lamenting their woes, they became very fond of each other, and finding that they were companions in misfortune, sought out one another everywhere, so that they might exchange consolation, in this wise setting on foot a deep and lasting attachment.

Those who had known Rolandine so very retiring that she would speak to none, were now greatly shocked on seeing her unceasingly with the well-born Bastard, and told her governess that she ought not to suffer their long talks together. The governess, therefore, remonstrated with Rolandine, and told her that every one was shocked at her conversing so freely with a man who was neither rich enough to marry her nor handsome enough to be her lover.

To this Rolandine, who had always been rebuked rather for austereness than for worldliness, replied—

"Alas, mother, you know that I cannot have a husband of my own condition, and that I have always shunned such as are handsome and young, fearing to fall into the same difficulties as others. And since this gentleman is discreet and virtuous, as you yourself know, and tells me nothing that is not honourable and right, what harm can I have done to you and to those that have spoken of the matter, by seeking from him some consolation in my grief?"

The poor old woman, who loved her mistress more than she loved herself, replied—

"I can see, my lady, that you speak the truth, and know that you are not treated by your father and mistress as you deserve to be. Nevertheless, since people are speaking about your honour in this way, you ought to converse with him no longer, even were he your own brother."

"Mother," said Rolandine, "if such be your counsel I will observe it; but 'tis a strange thing to be wholly without consolation in the world."

The Bastard came to talk with her according to his wont, but she told him everything that her governess had said to her, and, shedding tears, besought him to have no converse with her for a while, until the rumour should be past and gone; and to this he consented at her request.

Being thus cut off from all consolation, they both began, however, to feel such torment during their separation as neither had ever known before. For her part she did not cease praying to God, journeying and fasting; for love, heretofore unknown to her, caused her such exceeding disquiet as not to leave her an hour's repose. The well-born Bastard was no better off; but, as he had already resolved in his heart to love her and try to wed her, and had thought not only of his love but of the honour that it would bring him if he succeeded in his design, he reflected that he must devise a means of making his love known to her and, above all, of winning the governess to his side. This last he did by protesting to her the wretchedness of her poor mistress, who was being robbed of all consolation. At this the old woman, with many tears, thanked him for the honourable affection that he bore her mistress, and they took counsel together how he might speak with her. They planned that Rolandine should often feign to suffer from headache, to which noise is exceedingly distressful; so that, when her companions went into the Queen's apartment, she and the Bastard might remain alone, and in this way hold converse together.

The Bastard was overjoyed at this, and, guiding himself wholly by the governess's advice, had speech with his sweetheart whensoever he would. However, this contentment lasted no great while, for the Queen, who had but little love for Rolandine, inquired what she did so constantly in her room. Some one replied that it was on account of sickness, but another, who possessed too good a memory for the absent, declared that the pleasure she took in speaking with the Bastard must needs cause her headache to pass away.

The Queen, who deemed the venial sins of others to be mortal ones in Rolandine, sent for her and forbade her ever to speak to the Bastard except it were in the royal chamber or hall. The maiden gave no sign, but replied—

"Had I known, madam, that he or any one beside were displeasing to you, I should never have spoken to him."

Nevertheless she secretly cast about to find some other plan of which the Queen should know nothing, and in this she was successful. On Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays she was wont to fast, and would then stay with her governess in her own room, where, while the others were at supper, she was free to speak with the man whom she was beginning to love so dearly.

The more they were compelled to shorten their discourse, the more lovingly did they talk; for they stole the time even as a robber steals something that is of great worth. But, in spite of all their secrecy, a serving-man saw the Bastard go into the room one fast day, and reported the matter in a quarter where it was not concealed from the Queen. The latter was so wroth that the Bastard durst enter the ladies' room no more. Yet, that he might not lose the delight of converse with his love, he often made a pretence of going on a journey, and returned in the evening to the church or chapel of the castle (5) dressed as a Grey Friar or a Jacobin, or disguised so well in some other way that none could know him; and thither, attended by her governess, Rolandine would go to have speech with him.

5 This would be either the château of Amboise or that of Blois, we are inclined to think the latter, as Louis XII. more frequently resided there.—Ed.

Then, seeing how great was the love she bore him, he feared not to say—

"You see, fair lady, what risk I run in your service, and how the Queen has forbidden you to speak with me. You see, further, what manner of man is your father, who has no thought whatsoever of bestowing you in marriage. He has rejected so many excellent suitors, that I know of none, whether near or far, that can win you. I know that I am poor, and that you could not wed a gentleman that were not richer than I; yet, if love and good-will were counted wealth, I should hold myself for the richest man on earth. God has given you great wealth, and you are like to have even more. Were I so fortunate as to be chosen for your husband, I would be your husband, lover and servant all my life long; whereas, if you take one of equal consideration with yourself—and such a one it were hard to find—he will seek to be the master, and will have more regard for your wealth than for your person, and for the beauty of others than for your virtue; and, whilst enjoying the use of your wealth, he will fail to treat you, yourself, as you deserve. And now my longing to have this delight, and my fear that you will have none such with another, impel me to pray that you will make me a happy man, and yourself the most contented and best treated wife that ever lived."

When Rolandine heard the very words that she herself had purposed speaking to him, she replied with a glad countenance—

"I am well pleased that you have been the first to speak such words as I had a long while past resolved to say to you. For the two years that I have known you I have never ceased to turn over in my mind all the arguments for you and against you that I was able to devise; but now that I am at last resolved to enter into the married state, it is time that 1 should make a beginning and choose some one with whom I may look to dwell with tranquil mind. And I have been able to find none, whether handsome, rich, or nobly born, with whom my heart and soul could agree excepting yourself alone. I know that in marrying you I shall not offend God, but rather do what He enjoins, while as to his lordship my father, he has regarded my welfare so little, and has rejected so many offers, that the law suffers me to marry without fear of being disinherited; though, even if I had only that which is now mine, I should, in marrying such a husband as you, account myself the richest woman in the world. As to the Queen, my mistress, I need have no qualms in displeasing her in order to obey God, for never had she any in hindering me from any blessing that I might have had in my youth. But, to show you that the love I bear you is founded upon virtue and honour, you must promise that if I agree to this marriage, you will not seek its consummation until my father be dead, or until I have found a means to win his consent."

To this the Bastard readily agreed, whereupon they exchanged rings in token of marriage, and kissed each other in the church in the presence of God, calling upon Him to witness their promise; and never afterwards was there any other familiarity between them save kissing only.

This slender delight gave great content to the hearts of these two perfect lovers; and, secure in their mutual affection, they lived for some time without seeing each other. There was scarcely any place where honour might be won to which the Bastard did not go, rejoicing that he could not now continue a poor man, seeing that God had bestowed on him a rich wife; and she during his absence steadfastly cherished their perfect love, and made no account of any other living man. And although there were some who asked her in marriage, the only answer they had of her was that, since she had remained unwedded for so long a time, she desired to continue so for ever. (6)

6 The speeches of Rolandine and the Bastard should be compared with some of Clement Marot's elegies, notably with one in which he complains of having been surprised while conversing with his mistress in a church.—B. J.

This reply came to the ears of so many people, that the Queen heard of it and asked her why she spoke in that way. Rolandine replied that it was done in obedience to herself, who had never been pleased to marry her to any man who would have well and comfortably provided for her; accordingly, being taught by years and patience to be content with her present condition, she would always return a like answer whensoever any one spoke to her of marriage.

When the wars were over, (7) and the Bastard had returned to Court, she never spoke to him in presence of others, but always repaired to some church and there had speech with him under pretence of going to confession; for the Queen had forbidden them both, under penalty of death, to speak together except in public. But virtuous love, which recks naught of such a ban, was more ready to find them means of speech than were their enemies to spy them out; the Bastard disguised himself in the habit of every monkish order he could think of, and thus their virtuous intercourse continued, until the King repaired to a pleasure house he had near Tours. (8)

7 The wars here referred to would be one or another of Louis XII.'s Italian expeditions, probably that of 1507, when the battle of Aignadel was fought.—Ed. 8 This would no doubt be the famous château of Plessis-lez- Tours, within a mile of Tours, and long the favourite residence of Louis XI. Louis XII. is known to have sojourned at Plessis in 1507, at the time when the States-general conferred upon him the title of "Father of the People." English tourists often visit Plessis now adays in memory of Scott's "Quentin Durward," but only a few shapeless ruins of the old structure are left.—M. and Ed.

This, however, was not near enough for the ladies to go on foot to any other church but that of the castle, which was built in such a fashion that it contained no place of concealment in which the confessor would not have been plainly recognised.

But if one opportunity failed them, love found them another and an easier one, for there came to the Court a lady to whom the Bastard was near akin. This lady was lodged, together with her son, (9) in the King's abode; and the young Prince's room projected from the rest of the King's apartments in such a way that from his window it was possible to see and to speak to Rolandine, for his window and hers were just at the angle made by the two wings of the house.

9 This lady would be Louise of Savoy. She first came to the Court at Amboise in 1499, a circumstance which has led some commentators to place the incidents of this story at that date. But she was at Blois on various occasions between 1507 and 1509, to negotiate and attend the marriage of her daughter Margaret with the Duke of Alençon. Louis XII. having gone from Blois to Plessis in 1507, Louise of Savoy may well have followed him thither. Her son was, of course, the young Duke de Valois, afterwards Francis I.—Ed.

In this room of hers, which was over the King's presence-chamber, all the noble damsels that were Rolandine's companions were lodged with her. She, having many times observed the young Prince at his window, made this known to the Bastard through her governess; and he, having made careful observation of the place, feigned to take great pleasure in reading a book about the Knights of the Round Table (10) which was in the Prince's room.

10 Romances of chivalry were much sought after at this time. Not merely were there MS. copies of these adorned with miniatures, but we find that L'Histoire du Saint Gréai, La Vie et les Prophéties de Merlin, and Les Merveilleux Faits et Gestes du Noble Chevalier Lancelot du Lac were printed in France in the early years of the sixteenth century.—B.J.

And when every one was going to dinner, he would beg a valet to let him finish his reading, shut up in the room, over which he promised to keep good guard. The servants knew him to be a kinsman of his master and one to be trusted, let him read as much as he would. Rolandine, on her part, would then come to her window; and, so that she might be able to make a long stay at it, she pretended to have an infirmity in the leg, and accordingly dined and supped so early that she no longer frequented the ladies' table. She likewise set herself to work a coverlet of crimson silk, (11) and fastened it at the window, where she desired to be alone; and, when she saw that none was by, she would converse with her husband, who contrived to speak in such a voice as could not be overheard; and whenever any one was coming, she would cough and make a sign, so that the Bastard might withdraw in good time.

11 In the French, "Ung lût de reseul:" reticella—i.e., a kind of open work embroidery very fashionable in those days, and the most famous designers of which were Frederic Vinciolo, Dominic de Sara, and John Cousin the painter. Various sixteenth and seventeenth century books on needlework, still extant, give some curious information concerning this form of embroidery.—M.

Those who kept watch upon them felt sure that their love was past, for she never stirred from the room in which, as they thought, he could assuredly never see her, since it was forbidden him to enter it.

One day, however, the young Prince's mother, (12) being in her son's room, placed herself at the window where this big book lay, and had not long been there when one of Rolandine's companions, who was at the window in the opposite room, greeted her and spoke to her. The lady asked her how Rolandine did; whereon the other replied that she might see her if she would, and brought her to the window in her nightcap. Then, when they had spoken together about her sickness, they withdrew from the window on either side.

12 Louise of Savoy.

The lady, observing the big book about the Round Table, said to the servant who had it in his keeping—

"I am surprised that young folk can waste their time in reading such foolishness."

The servant replied that he marvelled even more that people accounted sensible and of mature age should have a still greater liking for it than the young; and he told her, as matter for wonderment, how her cousin the Bastard would spend four or five hours each day in reading this fine book. Straightway there came into the lady's mind the reason why he acted thus, and she charged the servant to hide himself somewhere, and take account of what the Bastard might do. This the man did, and found that the Bastard's book was the window to which Rolandine came to speak with him, and he, moreover, heard many a love-speech which they had thought to keep wholly secret.

On the morrow he related this to his mistress, who sent for the Bastard, and after chiding him forbade him to return to that place again; and in the evening she spoke of the matter to Rolandine, and threatened, if she persisted in this foolish love, to make all these practices known to the Queen.

Rolandine, whom nothing could dismay, vowed that in spite of all that folks might say she had never spoken to him since her mistress had forbidden her to do so, as might be learned both from her companions and from her servants and attendants. And as for the window, she declared that she had never spoken at it to the Bastard. He, however, fearing that the matter had been discovered, withdrew out of harm's way, and was a long time without returning to Court, though not without writing to Rolandine, and this in so cunning a manner that, in spite of the Queen's vigilance, never a week went by but she twice heard from him.

When he no longer found it possible to employ monks as messengers, as he had done at first, he would send a little page, dressed now in one colour and now in another; and the page used to stand at the doorways through which the ladies were wont to pass, and deliver his letters secretly in the throng. But one day, when the Queen was going out into the country, it chanced that one who was charged to look after this matter recognised the page, and hastened after him; but he, being keen-witted and suspecting that he was being pursued, entered the house of a poor woman who was boiling her pot on the fire, and there forthwith burned his letters. The gentleman who followed him stripped him naked and searched through all his clothes; but he could find nothing, and so let him go. And the boy being gone, the old woman asked the gentleman why he had so searched him.

"To find some letters," he replied, "which I thought he had upon him."

"You could by no means have found them," said the old woman, "they were too well hidden for that."

"I pray you," said the gentleman, in the hope of getting them before long, "tell me where they were."

However, when he heard that they had been thrown into the fire, he perceived that the page had proved more crafty than himself, and forthwith made report of the matter to the Queen.

From that time, however, the Bastard no longer employed the page or any other child, but sent an old servant of his, who, laying aside all fear of the death which, as he well knew, was threatened by the Queen against all such as should interfere in this matter, undertook to carry his master's letters to Rolandine. And having come to the castle where she was, he posted himself on the watch at the foot of a broad staircase, beside a doorway through which all the ladies were wont to pass. But a serving-man, who had aforetime seen him, knew him again immediately and reported the matter to the Queen's Master of the Household, who quickly came to arrest him. However, the discreet and wary servant, seeing that he was being watched from a distance, turned towards the wall as though he desired to make water, and tearing the letter he had into the smallest possible pieces, threw them behind a door. Immediately afterwards he was taken and thoroughly searched, and nothing being found on him, they asked him on his oath whether he had not brought letters, using all manner of threats and persuasions to make him confess the truth; but neither by promises nor threats could they draw anything from him.

Report of this having been made to the Queen, some one in the company bethought him that it would be well to look behind the door near which the man had been taken. This was done, and they found what they sought, namely the pieces of the letter. Then the King's confessor was sent for, and he, having put the pieces together on a table, read the whole of the letter, in which the truth of the marriage, that had been so carefully concealed, was made manifest; for the Bastard called Rolandine nothing but "wife." The Queen, who was in no mind, as she should have been, to hide her neighbour's transgressions, made a great ado about the matter, and commanded that all means should be employed to make the poor man confess the truth of the letter. And indeed, when they showed it to him, he could not deny it; but for all they could say or show, he would say no more than at first. Those who had him in charge thereupon brought him to the brink of the river, and put him into a sack, declaring that he had lied to God and to the Queen, contrary to proven truth. But he was minded to die rather than accuse his master, and asked for a confessor; and when he had eased his conscience as well as might be, he said to them—

"Good sirs, I pray you tell the Bastard, my master, that I commend the lives of my wife and children to him, for right willingly do I yield up my own in his service. You may do with me what you will, for never shall you draw from me a word against my master."

Thereupon, all the more to affright him, they threw him in the sack into the water, calling to him—

"If you will tell the truth, you shall be saved."

Finding, however, that he answered nothing, they drew him out again, and made report of his constancy to the Queen, who on hearing of it declared that neither the King nor herself were so fortunate in their followers as was this gentleman the Bastard, though he lacked even the means to requite them. She then did all that she could to draw the servant into her own service, but he would by no means consent to forsake his master. However, by the latter's leave, he at last entered the Queen's service, in which he lived in happiness and contentment.

The Queen, having learnt the truth of the marriage from the Bastard's letter, sent for Rolandine, whom with a wrathful countenance she several times called "wretch" instead of "cousin," reproaching her with the shame that she had brought both upon her father's house and her mistress by thus marrying without her leave or commandment.

Rolandine, who had long known what little love her mistress bore her, gave her but little in return. Moreover, since there was no love between them, neither was there fear; and as Rolandine perceived that this reprimand, given her in presence of several persons, was prompted less by affection than by a desire to put her to shame, and that the Queen felt more pleasure in chiding her than grief at finding her in fault, she replied with a countenance as glad and tranquil as the Queen's was disturbed and wrathful—

"If, madam, you did not know your own heart, such as it is, I would set forth to you the ill-will that you have long borne my father (13) and myself; but you do, indeed, know this, and will not deem it strange that all the world should have an inkling of it too. For my own part, madam, I have perceived it to my dear cost, for had you been pleased to favour me equally as you favour those who are not so near to you as myself, I were now married to your honour as well as to my own; but you passed me over as one wholly a stranger to your favour, and so all the good matches I might have made passed away before my eyes, through my father's neglect and the slenderness of your regard. By reason of this treatment I fell into such deep despair, that, had my health been strong enough in any sort to endure a nun's condition, I would have willingly entered upon it to escape from the continual griefs your harshness brought me.

13 Of all those with pretensions to the Duchy of Brittany, the Viscount de Rohan had doubtless the best claim, though he met with the least satisfaction. It was, however, this reason that led the Queen [Anne of Brittany] to treat him with such little regard. It was with mingled grief and resentment that this proud princess realised how real were the Viscount's rights; moreover, she never forgave him for having taken up arms against her in favour of France; and seeking an opportunity to avenge herself, she found one in giving the Viscount but little satisfaction in the matter of his pretensions."—Dora Morice's Histoire ecclésiastique et civile de Bretagne, Paris, 1756, vol. ii. p. 231.—L.

"Whilst in this despair I was sought by one whose lineage would be as good as my own if mutual love were rated as high as a marriage ring; for you know that his father would walk before mine. He has long wooed and loved me; but you, madam, who have never forgiven me the smallest fault nor praised me for any good deed, you—although you knew from experience that I was not wont to speak of love or worldly things, and that I led a more retired and religious life than any other of your maids—forthwith deemed it strange that I should speak with a gentleman who is as unfortunate in this life as I am myself, and one, moreover, in whose friendship I thought and looked to have nothing save comfort to my soul. When I found myself wholly baffled in this design, I fell into great despair, and resolved to seek my peace as earnestly as you longed to rob me of it; whereupon we exchanged words of marriage, and confirmed them with promise and ring. Wherefore, madam, methinks you do me a grievous wrong in calling me wicked, seeing that in this great and perfect love, wherein opportunity, had I so desired, would not have been lacking, no greater familiarity has passed between us than a kiss. I have waited in the hope that, before the consummation of the marriage, I might by the grace of God win my father's heart to consent to it. I have given no offence to God or to my conscience, for I have waited till the age of thirty to see what you and my father would do for me, and have kept my youth in such chastity and virtue that no living man can bring up aught against me. But when I found that I was old and without hope of being wedded suitably to my birth and condition, I used the reason that God has given me, and resolved to marry a gentleman after my own heart. And this I did not to gratify the lust of the eye, for you know that he is not handsome; nor the lust of the flesh, for there has been no carnal consummation of our marriage; nor the ambition and pride of life, for he is poor and of small rank; but I took account purely and simply of the worth that is in him, for which every one is constrained to praise him, and also of the great love that he bears me, and that gives me hope of having a life of quietness and kindness with him. Having carefully weighed all the good and the evil that may come of it, I have done what seems to me best, and, after considering the matter in my heart for two years, I am resolved to pass the remainder of my days with him. And so firm is my resolve that no torment that may be inflicted upon me, nor even death itself, shall ever cause me to depart from it. Wherefore, madam, I pray you excuse that which is indeed very excusable, as you yourself must realise, and suffer me to dwell in that peace which I hope to find with him."

The Queen, finding her so steadfast of countenance and so true of speech, could make no reply in reason, but continued wrathfully rebuking and reviling her, bursting into tears and saying—

"Wretch that you are! instead of humbling yourself before me, and repenting of so grievous a fault, you speak hardily with never a tear in your eye, and thus clearly show the obstinacy and hardness of your heart. But if the King and your father give heed to me, they will put you into a place where you will be compelled to speak after a different fashion."

"Madam," replied Rolandine, "since you charge me with speaking too hardily, I will e'en be silent if you give me not permission to reply to you."

Then, being commanded to speak, she went on—

"'Tis not for me, madam, to speak to you, my mistress and the greatest Princess in Christendom, hardily and without the reverence that I owe to you, nor have I purposed doing so; but I have no defender to speak for me except the truth, and as this is known to me alone, I am forced to utter it fearlessly in the hope that, when you know it, you will not hold me for such as you have been pleased to name me. I fear not that any living being should learn how I have comported myself in the matter that is laid to my charge, for I know that I have offended neither against God nor against my honour. And this it is that enables me to speak without fear; for I feel sure that He who sees my heart is on my side, and with such a Judge in my favour, I were wrong to fear such as are subject to His decision. Why should I weep? My conscience and my heart do not at all rebuke me, and so far am I from repenting of this matter, that, were it to be done over again, I should do just the same. But you, madam, have good cause to weep both for the deep wrong that you have done me throughout my youth, and for that which you are now doing me, in rebuking me publicly for a fault that should be laid at your door rather than at mine. Had I offended God, the King, yourself, my kinsfolk or my conscience, I were indeed obstinate and perverse if I did not greatly repent with tears; but I may not weep for that which is excellent, just and holy, and which would have received only commendation had you not made it known before the proper time. In doing this, you have shown that you had a greater desire to compass my dishonour than to preserve the honour of your house and kin. But, since such is your pleasure, madam, I have nothing to say against it; command me what suffering you will, and I, innocent though I am, will be as glad to endure as you to inflict it. Wherefore, madam, you may charge my father to inflict whatsoever torment you would have me undergo, for I well know that he will not fail to obey you. It is pleasant to know that, to work me ill, he will wholly fall in with your desire, and that as he has neglected my welfare in submission to your will, so will he be quick to obey you to my hurt. But I have a Father in Heaven, and He will, I am sure, give me patience equal to all the evils that I foresee you preparing for me, and in Him alone do I put my perfect trust."

The Queen, beside herself with wrath, commanded that Rolandine should be taken from her sight and put into a room alone, where she might have speech with no one. However, her governess was not taken from her, and through her Rolandine acquainted the Bastard with all that had befallen her, and asked him what he would have her do. He, thinking that his services to the King might avail him something, came with all speed to the Court. Finding the King at the chase, he told him the whole truth, entreating him to favour a poor gentleman so far as to appease the Queen and bring about the consummation of the marriage.

The King made no reply except to ask—

"Do you assure me that you have wedded her?"

"Yes, sire," said the Bastard, "but by word of mouth alone; however, if it please you, we'll make an ending of it."

The King bent his head, and, without saying anything more, returned straight towards the castle, and when he was nigh to it summoned the Captain of his Guard, and charged him to take the Bastard prisoner.

However, a friend who knew and could interpret the King's visage, warned the Bastard to withdraw and betake himself to a house of his that was hard by, saying that if the King, as he expected, sought for him, he should know of it forthwith, so that he might fly the kingdom; whilst if, on the other hand, things became smoother, he should have word to return. The Bastard followed this counsel, and made such speed that the Captain of the Guards was not able to find him.

The King and Queen took counsel together as to what they should do with the hapless lady who had the honour of being related to them, and by the Queen's advice it was decided that she should be sent back to her father, and that he should be made acquainted with the whole truth.

But before sending her away they caused many priests and councillors to speak with her and show her that, since her marriage consisted in words only, it might by mutual agreement readily be made void; and this, they urged, the King desired her to do in order to maintain the honour of the house to which she belonged.

She made answer that she was ready to obey the King in all such things as were not contrary to her conscience, but that those whom God had brought together man could not put asunder. She therefore begged them not to tempt her to anything so unreasonable; for if love and goodwill founded on the fear of God were the true and certain marriage ties, she was linked by bonds that neither steel nor flame nor water could sever. Death alone might do this, and to death alone would she resign her ring and her oath. She therefore prayed them to gainsay her no more; for so strong of purpose was she that she would rather keep faith and die than break it and live.

This steadfast reply was repeated to the King by those whom he had appointed to speak with her, and when it was found that she could by no means be brought to renounce her husband, she was sent to her father, and this in so pitiful a plight that all who beheld her pass wept to see her. And although she had done wrong, her punishment was so grievous and her constancy so great, that her wrongdoing was made to appear a virtue.

When her father heard the pitiful tale, he would not see her, but sent her away to a castle in a forest, which he had aforetime built for a reason well worthy to be related. (14) There he kept her in prison for a long time, causing her to be told that if she would give up her husband he would treat her as his daughter and set her free.

14 The famous château of Josselin in Morbihan. See notes to Tale XL., vol. lv.—Ed.

Nevertheless she continued firm, for she preferred the bonds of prison together with those of marriage, to all the freedom in the world without her husband. And, judging from her countenance, all her woes seemed but pleasant pastimes to her, since she was enduring them for one she loved.

And now, what shall I say of men? The Bastard, who was so deeply beholden to her, as you have seen, fled to Germany where he had many friends, and there showed by his fickleness that he had sought Rolandine less from true and perfect love than from avarice and ambition; for he fell deeply in love with a German lady, and forgot to write to the woman who for his sake was enduring so much tribulation. However cruel Fortune might be towards them, they were always able to write to each other, until he conceived this foolish and wicked love. And Rolandine's heart gaining an inkling of it, she could no longer rest.

And afterwards, when she found that his letters were colder and different from what they had been before, she suspected that some new love was separating her from her husband, and doing that which all the torments and afflictions laid upon herself had been unable to effect. Nevertheless, her perfect love would not pass judgment on mere suspicion, so she found a means of secretly sending a trusty servant, not to carry letters or messages to him, but to watch him and discover the truth. When this servant had returned from his journey, he told her that the Bastard was indeed deeply in love with a German lady, and that according to common report he was seeking to marry her, for she was very rich.

These tidings brought extreme and unendurable grief to Rolandine's heart, so that she fell grievously sick. Those who knew the cause of her sickness, told her on behalf of her father that, with this great wickedness on the part of the Bastard before her eyes, she might now justly renounce him. They did all they could to persuade her to that intent, but, notwithstanding her exceeding anguish, she could not be brought to change her purpose, and in this last temptation again gave proof of her great love and surpassing virtue. For as love grew less and less on his part, so did it grow greater on hers, and in this way make good that which was lost. And when she knew that the entire and perfect love that once had been shared by both remained but in her heart alone, she resolved to preserve it there until one or the other of them should die. And the Divine Goodness, which is perfect charity and true love, took pity upon her grief and long suffering, in such wise that a few days afterwards the Bastard died while occupied in seeking after another woman. Being advised of this by certain persons who had seen him laid in the ground, she sent to her father and begged that he would be pleased to speak with her.

Her father, who had never spoken to her since her imprisonment, came without delay. He listened to all the pleas that she had to urge, and then, instead of rebuking her or killing her as he had often threatened, he took her in his arms and wept exceedingly.

"My daughter," he said, "you are more in the right than I, for if there has been any wrongdoing in this matter, I have been its principal cause. But now, since God has so ordered it, I would gladly atone for the past."

He took her home and treated her as his eldest daughter. A gentleman who bore the same name and arms as did her own family sought her in marriage; he was very sensible and virtuous, (15) and he thought so much of Rolandine, whom he often visited, that he gave praise to what others blamed in her, perceiving that virtue had been her only aim. The marriage, being acceptable both to Rolandine and to her father, was concluded without delay.

It is true, however, that a brother she had, the sole heir of their house, would not grant her a portion, for he charged her with having disobeyed her father. And after his father's death he treated her so harshly that she and her husband (who was a younger son) had much ado to live. (16)

15 Peter de Rohan-Gié, Lord of Frontenay, third son of Peter de Rohan, Lord of Gié, Marshal of Prance and preceptor to Francis I. As previously stated, the marriage took place in 1517, and eight years later the husband was killed at Pavia.—Ed. 16 Anne de Rohan (Rolandine) had two brothers, James and Claud. Both died without issue. Some particulars concerning them will be found in the notes to Tale XL. The father's death, according to Anselme, took place in 1516, that is, prior to Anne's marriage.—Ed.

However, God provided for them, for the brother that sought to keep everything died suddenly one day, leaving behind him both her wealth, which he was keeping back, and his own.

Thus did she inherit a large and rich estate, whereon she lived piously and virtuously and in her husband's love. And after she had brought up the two sons that God gave to them, (17) she yielded with gladness her soul to Him in whom she had at all times put her perfect trust.

17 Anne's sons were René and Claud. Miss Mary Robinson (The Fortunate Lovers, London, 1887) believes René to be "Saffredent," and his wife Isabel d'Albret, sister of Queen Margaret's husband Henry of Navarre, to be "Nomerfide."—Ed.

"Now, ladies, let the men who would make us out so fickle come forward and point to an instance of as good a husband as this lady was a good wife, and of one having like faith and steadfastness. I am sure they would find it so difficult to do this, that I will release them from the task rather than put them to such exceeding toil. But as for you, ladies, I would pray you, for the sake of maintaining your own fair fame, either to love not at all, or else to love as perfectly as she did. And let none among you say that this lady offended against her honour, seeing that her constancy has served to heighten our own."

"In good sooth, Parlamente," said Oisille, "you have indeed told us the story of a woman possessed of a noble and honourable heart; but her constancy derives half its lustre from the faithlessness of a husband that could leave her for another."

"I think," said Longarine, "that the grief so caused must have been the hardest to bear. There is none so heavy that the love of two united lovers cannot support it; but when one fails in his duty, and leaves the whole of the burden to the other, the load becomes too heavy to be endured."

"Then you ought to pity us," said Geburon, "for we have to bear the whole burden of love, and you will not put out the tip of a finger to relieve us."

"Ah, Geburon," said Parlamente, "the burdens of men and of women are often different enough. The love of a woman, being founded on godliness and honour, is just and reasonable, and any man that is false to it must be reckoned a coward, and a sinner against God and man. On the other hand, most men love only with reference to pleasure, and women, being ignorant of their ill intent, are sometimes ensnared; but when God shows them how vile is the heart of the man whom they deemed good, they may well draw back to save their honour and reputation, for soonest ended is best mended."

"Nay, that is a whimsical idea of yours," said Hircan, "to hold that an honourable woman may in all honour betray the love of a man; but that a man may not do as much towards a woman. You would make out that the heart of the one differs from that of the other; but for my part, in spite of their differences in countenance and dress, I hold them to be alike in inclination, except indeed that the guilt which is best concealed is the worst."

Thereto Parlamente replied with some heat—

"I am well aware that in your opinion the best women are those whose guilt is known."

"Let us leave this discourse," said Simontault; "for whether we take the heart of man or the heart of woman, the better of the twain is worth nothing. And now let us see to whom Parlamente is going to give her vote, so that we may hear some fine tale."

"I give it," she said, "to Geburon."

"Since I began," (18) he replied, "by talking about the Grey friars, I must not forget those of Saint Benedict, nor an adventure in which they were concerned in my own time. Nevertheless, in telling you the story of a wicked monk, I do not wish to hinder you from having a good opinion of such as are virtuous; but since the Psalmist says 'all men are liars,' and in another place, 'there is none that doeth good, no not one,' (19) I think we are bound to look upon men as they really are. If there be any virtue in them, we must attribute it to Him who is its source, and not to the creature. Most people deceive themselves by giving overmuch praise or glory to the latter, or by thinking that there is something good in themselves. That you may not deem it impossible for exceeding lust to exist under exceeding austerity, listen to what befel in the days of King Francis the First."

18 See the first tale he tells, No. 5, vol. i.—Ed. 19 Psalms cxvi. 11 and xiv. 3.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.