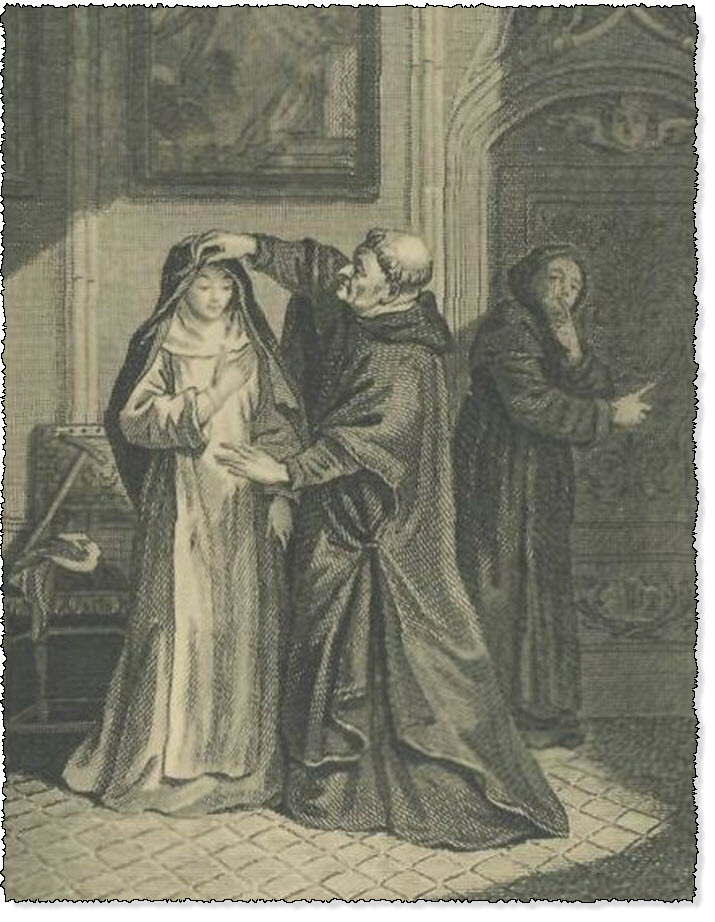

Sister Marie and the Prior

The Heptameron - Day 3, Tale 22 - Sister Marie and the Prior

TALE XXII.

Sister Marie Heroet, being unchastely solicited by a Prior of Saint-Martin-in-the-Fields, was by the grace of God enabled to overcome his great temptations, to the Prior's exceeding confusion and her own glory. (1) 1 This story is historical, and though M. Frank indicates points of similarity between it and No. xxvii. of St. Denis' Comptes du Monde Adventureux, and No. vi. of Masuccio de Solerac's Novellino, these are of little account when one remembers that the works in question were written posterior to the Heptameron. The incidents related in the tale must have occurred between 1530 and 1535. The Abbey of Saint- Martin-in-the-Fields stood on the site of the present Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers, Paris.—Ed.

In the city of Paris there was a Prior of Saint-Martin-in-the-Fields, whose name I will keep secret for the sake of the friendship I bore him. Until he reached the age of fifty years, his life was so austere that the fame of his holiness was spread throughout the entire kingdom, and there was not a prince or princess but showed him high honour when he came to visit them. There was further no monkish reform that was not wrought by his hand, so that people called him the "father of true monasticism." (2)

He was chosen visitor to the illustrious order of the "Ladies of Fontevrault," (3) by whom he was held in such awe that, when he visited any of their convents, the nuns shook with very fear, and to soften his harshness towards them would treat him as though he had been the King himself in person. At first he would not have them do this, but at last, when he was nearly fifty-five years old, he began to find the treatment he had formerly contemned very pleasant; and reckoning himself the mainstay of all monasticism, he gave more care to the preservation of his health than had heretofore been his wont. Although the rules of his order forbade him ever to partake of flesh, he granted himself a dispensation (which was more than he ever did for another), declaring that the whole burden of conventual affairs rested upon him; for which reason he feasted himself so well that, from being a very lean monk he became a very fat one.

2 This prior was Stephen Gentil, who succeeded Philip Bourgoin on December 15, 1508, and died November 6, 1536. The Gallia Christiana states that in 1524 he reformed an abbey of the diocese of Soissons, but makes no mention of his appointment as visitor to the abbey of Fontevrault. Various particulars concerning him will be found in Manor's Monasterii Regalis S. Martini de Campis, &c. Parisiis, 1636, and in Gallia Christiana, vol. vii. col. 539.—L. 3 The abbey of Fontevrault, near Saumur, Maine-et-Loire, was founded in 1100 by Robert d'Arbrissel, and comprised two conventual establishments, one for men and the other for women. Prior to his death, d'Arbrissel abdicated his authority in favour of Petronilla de Chemillé, and from her time forward monks and nuns alike were always under the sway of an abbess—this being the only instance of the kind in the history of the Roman Catholic Church. Fourteen of the abbesses were princesses, and several of these were of the blood royal of France. In the abbey church were buried our Henry II., Eleanor of Guienne, Richard Coeur-de-Lion, and Isabella of Angoulême; their tombs are still shown, though the abbey has become a prison, and its church a refectory.— Ed.

Together with this change of life there was wrought also a great change of heart, so that he now began to cast glances upon countenances which aforetime he had looked at only as a duty; and, contemplating charms which were rendered even more desirable by the veil, he began to hanker after them. Then, to satisfy this longing, he sought out such cunning devices that at last from being a shepherd he became a wolf, so that in many a convent, where there chanced to be a simple maiden, he failed not to beguile her. But after he had continued this evil life for a long time, the Divine Goodness took compassion upon the poor, wandering sheep, and would no longer suffer this villain's triumph to endure, as you shall hear.

One day he went to visit the convent of Gif, (4) not far from Paris, and while he was confessing all the nuns, it happened that there was one among them called Marie Heroet, whose speech was so gentle and pleasing that it gave promise of a countenance and heart to match.

4 Gif, an abbey of the Benedictine order, was situated at five leagues from Paris, in the valley of Chevreuse, on the bank of the little river Yvette. A few ruins of it still remain. It appears to have been founded in the eleventh century.—See Le Beuf s Histoire du Diocèse de Paris, vol. viii. part viii. p. 106, and Gallia Christiana, vol. vii. col. 596.—L. and D.

The mere sound of her voice moved him with a passion exceeding any that he had ever felt for other nuns, and, while speaking to her, he bent low to look at her, and perceiving her rosy, winsome mouth, could not refrain from lifting her veil to see whether her eyes were in keeping therewith. He found that they were, and his heart was filled with so ardent a passion that, although he sought to conceal it, his countenance became changed, and he could no longer eat or drink. When he returned to his priory, he could find no rest, but passed his days and nights in deep disquiet, seeking to devise a means whereby he might accomplish his desire, and make of this nun what he had already made of many others. But this, he feared, would be difficult, seeing that he had found her to be prudent of speech and shrewd of understanding; moreover, he knew himself to be old and ugly, and therefore resolved not to employ words but to seek to win her by fear.

Heptameron Story 22

Accordingly, not long afterwards, he returned to the convent of Gif aforesaid, where he showed more austerity than he had ever done before, and spoke wrathfully to all the nuns, telling one that her veil was not low enough, another that she carried her head too high, and another that she did not do him reverence as a nun should do. So harsh was he in respect of all these trifles, that they feared him as though he had been a god sitting on the throne of judgment.

Being gouty, he grew very weary in visiting all the usual parts of the convent, and it thus came to pass that about the hour for vespers, an hour which he had himself fixed upon, he found himself in the dormitory, when the Abbess said to him—

"Reverend father, it is time to go to vespers."

"Go, mother," he replied, "do you go to vespers. I am so weary that I will remain here, yet not to rest but to speak to Sister Marie, of whom I have had a very bad report, for I am told that she prates like a worldly-minded woman."

The Abbess, who was aunt to the maiden's mother, begged him to reprove her soundly, and left her alone with him and a young monk who accompanied him.

When he found himself alone with Sister Marie, he began to lift up her veil, and to tell her to look at him. She answered that the rule of her order forbade her to look at men.

"It is well said, my daughter," he replied, "but you must not consider us monks as men."

Then Sister Marie, fearing to sin by disobedience, looked him in the face; but he was so ugly that she though it rather a penance than a sin to look at him.

The good father, after telling her at length of his goodwill towards her, sought to lay his hand upon her breasts; but she repulsed him, as was her duty; whereupon, in great wrath, he said to her—

"Should a nun know that she has breasts?"

"I know that I have," she replied, "and certes neither you nor any other shall ever touch them. I am not so young and ignorant that I do not know the difference between what is sin and what is not."

When he saw that such talk would not prevail upon her, he adopted a different plan, and said—

"Alas, my daughter, I must make known to you my extreme need. I have an infirmity which all the physicians hold to be incurable unless I have pleasure with some woman whom I greatly love. For my part, I would rather die than commit a mortal sin; but, when it comes to that, I know that simple fornication is in no wise to be compared with the sin of homicide. So, if you love my life, you will preserve it for me, as well as your own conscience from cruelty."

She asked him what manner of pleasure he desired to have. He replied that she might safely surrender her conscience to his own, and that he would do nothing that could be a burden to either.

Then, to let her see the beginning of the pastime that he sought, he took her in his arms and tried to throw her upon a bed. She, recognising his evil purpose, defended herself so well with arms and voice that he could only touch her garments. Then, when he saw that all his devices and efforts were being brought to naught, he behaved like a madman and one devoid not only of conscience but of natural reason, for, thrusting his hand under her dress, he scratched wherever his nails could reach with such fury that the poor girl shrieked out, and fell swooning at full length upon the floor.

Hearing this cry, the Abbess came into the dormitory; for while at vespers she had remembered that she had left her niece's daughter alone with the good father, and feeling some scruples of conscience, she had left the chapel and repaired to the door of the dormitory in order to learn what was going on. On hearing her niece's voice, she pushed open the door, which was being held by the young monk.

And when the Prior saw the Abbess coming, he pointed to her niece as she lay in a swoon, and said—

"Assuredly, mother, you are greatly to blame that you did not inform me of Sister Marie's condition. Knowing nothing of her weakness, I caused her to stand before me, and, while I was reproving her, she swooned away as you see."

They revived her with vinegar and other remedies, and found that she had wounded her head in her fall. When she was recovered, the Prior, fearing that she would tell her aunt the reason of her indisposition, took her aside and said to her—

"I charge you, my daughter, if you would be obedient and hope for salvation, never to speak of what I said to you just now. You must know that it was my exceeding love for you that constrained me, but since I see that you do not wish to love me, I will never speak of it to you again. However, if you be willing, I promise to have you chosen Abbess of one of the three best convents in the kingdom."

She replied that she would rather die in perpetual imprisonment than have any lover save Him who had died for her on the cross, for she would rather suffer with Him all the evils the world could inflict than possess without Him all its blessings. And she added that he must never again speak to her in such a manner, or she would inform the Abbess; whereas, if he kept silence, so would she.

Thereupon this evil shepherd left her, and in order to make himself appear quite other than he was, and to again have the pleasure of looking upon her he loved, he turned to the Abbess and said—

"I beg, mother, that you will cause all your nuns to sing a Salve Regina in honour of that virgin in whom I rest my hope."

While this was being done, the old fox did nothing but shed tears, not of devotion, but of grief at his lack of success. All the nuns, thinking that it was for love of the Virgin Mary, held him for a holy man, but Sister Marie, who knew his wickedness, prayed in her heart that one having so little reverence for virginity might be brought to confusion.

And so this hypocrite departed to St. Martin's, where the evil fire that was in his heart did not cease burning night and day alike, prompting him to all manner of devices in order to compass his ends. As he above all things feared the Abbess, who was a virtuous woman, he hit upon a plan to withdraw her from the convent, and betook himself to Madame de Vendôme, who was at that time living at La Fère, where she had founded and built a convent of the Benedictine order called Mount Olivet. (5)

5 This is Mary of Luxemburg, Countess of St. Paul-de- Conversan, Marie and Soissons, who married, first, James of Savoy, and secondly, Francis de Bourbon, Count of Vendôme. The latter, who accompanied Charles VIII. to Italy, was killed at Vercelli in October 1495, when but twenty-five years old. His widow did not marry again, but retired to her château of La Fère near Laon (Aisne), where late in 1518 she founded a convent of Benedictine nuns, which, according to the Gallia Christiana, she called the convent of Mount Calvary. This must be the establishment alluded to by Queen Margaret, who by mistake has called it Mount Olivet, i.e., the Mount of Olives. Madame de Vendôme died at a very advanced age on April 1, 1546.—See Anselme's Histoire Généalogique, vol. i. p. 326.—L.

Speaking in the quality of a prince of reformers, he gave her to understand that the Abbess of the aforesaid Mount Olivet lacked the capacity to govern such a community. The worthy lady begged him to give her another that should be worthy of the office, and he, who asked nothing better, counselled her to have the Abbess of Gif, as being the most capable in France. Madame de Vendôme sent for her forthwith, and set her over the convent of Mount Olivet.

As the Prior of St. Martin's had every monastic vote at his disposal, he caused one who was devoted to him to be chosen Abbess of Gif, and this being accomplished, he went to Gif to try once more whether he might win Sister Marie Heroet by prayers or honied words. Finding that he could not succeed, he returned in despair to his priory of St. Martin's, and in order to achieve his purpose, to revenge himself on her who was so cruel to him, and further to prevent the affair from becoming known, he caused the relics of the aforesaid convent of Gif to be secretly stolen at night, and accusing the confessor of the convent, a virtuous and very aged man, of having stolen them, he cast him into prison at St. Martin's.

Whilst he held him captive there, he stirred up two witnesses who in ignorance signed what the Prior commanded them, which was a statement that they had seen the confessor in a garden with Sister Marie, engaged in a foul and wicked act; and this the Prior sought to make the old monk confess. But he, who knew all the Prior's misdoings, entreated him to bring him before the Chapter, saying that there, in presence of all the monks, he would tell the truth of all that he knew. The Prior, fearing that the confessor's justification would be his own condemnation, would in no wise grant this request; and, finding him firm of purpose, he treated him so ill in prison that some say he brought about his death, and others that he forced him to lay aside his robe and betake himself out of the kingdom of France. Be that as it may, the confessor was never seen again.

The Prior, thinking that he had now a sure hold upon Sister Marie, repaired to the convent, where the Abbess, chosen for this purpose, gainsaid him in nothing. There he began to exercise his authority as visitor, and caused all the nuns to come one after the other into a room that he might hear them, as is the fashion at a visitation. When the turn of Sister Marie, who had now lost her good aunt, had come, he began speaking to her in this wise—

"Sister Marie, you know of what crime you are accused, and that your pretence of chastity has availed you nothing, since you are well known to be the very contrary of chaste."

"Bring here my accuser," replied Sister Marie, with steadfast countenance, "and you will see whether in my presence he will abide by his evil declaration."

"No further proof is needed," he said, "since the confessor has been found guilty."

"I hold him for too honourable a man," said Sister Marie, "to have confessed so great a lie; but even should he have done so, bring him here before me, and I will prove the contrary of what he says."

The Prior, finding that he could in no wise move her, thereupon said—

"I am your father, and seek to save your honour. For this reason I will leave the truth of the matter to your own conscience, and will believe whatever it bids you say. I ask you and conjure you on pain of mortal sin to tell me truly whether you were indeed a virgin when you were placed in this house?"

"My father," she replied, "I was then but five years old, and that age must in itself testify to my virginity."

"Well, my daughter," said the Prior, "have you not since that time lost this flower?"

She swore that she had kept it, and that she had had no hindrance in doing so except from himself. Whereto he replied that he could not believe it, and that the matter required proof.

"What proof," she asked, "would you have?"

"The same as from the others," said the Prior; "for as I am visitor of souls, even so am I visitor of bodies also. Your abbesses and prioresses have all passed through my hands, and you need have no fear if I visit your virginity. Wherefore throw yourself upon the bed, and lift the forepart of your garments over your face."

"You have told me so much of your wicked love for me," Sister Marie replied in wrath, "that I think you seek rather to rob me of my virginity than to visit it. So understand that I shall never consent."

Thereupon he said to her that she was excommunicated for refusing him the obedience which Holy Church commanded, and that, if she did not consent, he would dishonour her before the whole Chapter by declaring the evil that he knew of between herself and the confessor.

But with fearless countenance she replied—

"He that knows the hearts of His servants shall give me as much honour in His presence as you can give me shame in the presence of men; and since your wickedness goes so far, I would rather it wreaked its cruelty upon me than its evil passion; for I know that God is a just judge."

Then the Prior departed and assembled the whole Chapter, and, causing Sister Marie to appear on her knees before him, he said to her with wondrous malignity—

"Sister Marie, it grieves me to see that the good counsels I have given you have been of no effect, and to find you fallen into such evil ways that, contrary to my wont, I must needs lay a penance upon you. I have examined your confessor concerning certain crimes with which he is charged, and he has confessed to me that he has abused your person in the place where the witnesses say that they saw him. And so I command that, whereas I had formerly raised you to honourable rank as Mistress of the Novices, you shall now be the lowest placed of all, and further, shall eat only bread and water on the ground, and in presence of all the Sisters, until you have shown sufficient penitence to receive forgiveness."

Sister Marie had been warned by one of her companions, who was acquainted with the whole matter, that if she made any reply displeasing to the Prior, he would put her in pace—that is, in perpetual imprisonment—and she therefore submitted to this sentence, raising her eyes to heaven, and praying Him who had enabled her to withstand sin, to grant her patience for the endurance of tribulation. The Prior of St. Martin's further commanded that for the space of three years she should neither speak with her mother or kinsfolk when they came to see her, nor send any letters save such as were written in community.

The miscreant then went away and returned no more, and for a long time the unhappy maiden continued in the tribulation that I have described. But her mother, who loved her best of all her children, was much astonished at receiving no tidings from her; and told one of her sons, who was a prudent and honourable gentleman, (6) that she thought her daughter was dead, and that the nuns were hiding it from her in order that they might receive the yearly payment. She, therefore, begged him to devise some means of seeing his sister.

6 It is conjectured by M. Lacroix that this "prudent and honourable gentleman," Mary Heroet's brother, was Antoine Heroet or Hérouet, alias La Maisonneuve, who at one time was a valet and secretary to Queen Margaret, and so advanced himself in life that he died Bishop of Digne in 1544. He was the author of La Parfaite Amie, L'Androgyne, and De n'aimer point sans être aimé, poems of a semi-metaphysical, semi- amorous character such as might have come from Margaret's own pen. Whether he was Mary Heroet's brother or not, it is at least probable that he was her relative.-B. J. and L.

He went forthwith to the convent, where he met with the wonted excuses, being told that for three years his sister had not stirred from her bed. But this did not satisfy him, and he swore that, if he did not see her, he would climb over the walls and force his way into the convent. Thereupon, being in great fear, they brought his sister to him at the grating, though the Abbess stood so near that she could not tell her brother aught that was not heard. But she had prudently set down in writing all that I have told you, together with a thousand others of the Prior's devices to deceive her, which 'twould take too long to relate.

Yet I must not omit to mention that at the time when her aunt was Abbess, the Prior, thinking that his ugliness was the cause of her refusal, had caused Sister Marie to be tempted by a handsome young monk, in the hope that if she yielded to this man through love, he himself might afterwards obtain her through fear. The young monk aforesaid spoke to her in a garden with gestures too shameful to be mentioned, whereat the poor maiden ran to the Abbess, who was talking with the Prior, and cried out—

"Mother, they are not monks, but devils, who visit us here!"

Thereupon the Prior, in great fear of discovery, began to laugh, and said—

"Assuredly, mother, Sister Marie is right."

Then, taking Sister Marie by the hand, he said to her in presence of the Abbess—

"I had heard that Sister Marie spoke very well, and so constantly that she was deemed to be worldly-minded. For this reason I constrained myself, contrary to my natural inclination, to speak to her in the way that worldly men speak to women—at least in books, for in point of experience I am as ignorant as I was on the day when I was born. Thinking, however, that only my years and ugliness led her to discourse in so virtuous a fashion, I commanded my young monk to speak to her as I myself had done, and, as you see, she has virtuously resisted him. So highly, therefore, do I think of her prudence and virtue, that henceforward she shall rank next after you and shall be Mistress of the Novices, to the intent that her excellent disposition may ever increase in virtue."

This act, with many others, was done by this worthy monk during the three years that he was in love with the nun. She, however, as I have said, gave her brother in writing, through the grating, the whole story of her pitiful fortunes; and this her brother brought to her mother, who came, overwhelmed with despair, to Paris. Here she found the Queen of Navarre, only sister to the King, and showing her the piteous story, said—

"Madam, trust no more in these hypocrites. I thought that I had placed my daughter within the precincts of Paradise, or on the high road thither, whereas I have placed her in the precincts of Hell, and in the hands of the vilest devils imaginable. The devils, indeed, do not tempt us unless temptation be our pleasure, but these men will take by force when they cannot win by love."

The Queen of Navarre was in great concern, for she trusted wholly in the Prior of St. Martin's, to whose care she had committed her sisters-inlaw, the Abbesses of Montivilliers and Caen. (7) On the other hand, the enormity of the crime so horrified her and made her so desirous of avenging the innocence of this unhappy maiden, that she communicated the matter to the King's Chancellor, who happened also to be Legate in France. (8)

7 The abbess of Montivilliers was Catherine d'Albret, daughter of John d'Albret, King of Navarre and sister of Queen Margaret's husband, Henry. At first a nun at the abbey of St. Magdalen at Orleans, she became twenty-eighth abbess of Montivilliers near Havre. She was still living in 1536. (Gallia Christ., vol. xi. col. 285). The abbess of Caen was Magdalen d'Albret, Catherine's sister. She took the veil at Fontevrault in 1527, subsequently became thirty-third abbess of the Trinity at Caen, and died in November 1532. (Gallia Christ., vol. xi. col. 436).—L. 8 This is the famous Antony Duprat, Francis I.'s favourite minister. Born in 1463, he became Chancellor in 1515, and his wife dying soon afterwards, he took orders, with the result that he was made Archbishop of Sens and Cardinal. It was in 1530 that he was appointed Papal Legate in France, so that the incidents related in this tale cannot have occurred at an earlier date. Duprat died in July 1535, of grief, it is said, because Francis I. would not support him in his ambitious scheme to secure possession of the papal see, as successor to Clement VII.-B. J. and Ed.

The Prior was sent for, but could find nothing to plead except that he was seventy years of age, and addressing himself to the Queen of Navarre he begged that, for all the good she had ever wished to do him, and in token of all the services he had rendered or had desired to render her, she would be pleased to bring these proceedings to a close, and he would acknowledge that Sister Marie was a pearl of honour and chastity.

On hearing this, the Queen of Navarre was so astonished that she could make no reply, but went off and left him there. The unhappy man then withdrew in great confusion to his monastery, where he would suffer none to see him, and where he lived only one year afterwards. And Sister Marie Heroet, now reputed as highly as she deserved to be, by reason of the virtues that God had given her, was withdrawn from the convent of Gif, where she had endured so much evil, and was by the King made Abbess of the the convent of Giy (9) near Montargis.

9 Giy-les-Nonains, a little village on the river Ouanne, at two leagues and a half from Montargis, department of the Loiret.—L.

This convent she reformed, and there she lived like one filled with the Spirit of God, whom all her life long she ever praised for having of His good grace restored to her both honour and repose.

"There, ladies, you have a story which clearly proves the words of the Gospel, that 'God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty, and things which are despised of men hath God chosen to bring to nought the glory of those who think themselves something but are in truth nothing.' (10) And remember, ladies, that without the grace of God there is no good at all in man, just as there is no temptation that with His assistance may not be overcome. This is shown by the abasement of the man who was accounted just, and the exaltation of her whom men were willing to deem a wicked sinner. Thus are verified Our Lord's words, 'Whosoever exalteth himself shall be abased; and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted.'" (11)

10 I Corinthians i. 27, 28, slightly modified. 11 St. Luke xiv. 11 and xviii. 14.

"Alas," said Oisille, "how many virtuous persons did that Prior deceive! For I saw people put more trust in him than even in God."

"I should not have done so," said Nomerfide, "for such is my horror of monks that I could not confess to one. I believe they are worse than all other men, and never frequent a house without leaving disgrace or dissension behind them."

"There are good ones among them," said Oisille, "and they ought not to be judged by the bad alone; but the best are those that least often visit laymen's houses and women."

"You are right," said Ennasuite. "The less they are seen, the less they are known, and therefore the more highly are they esteemed; for companionship with them shows what they really are."

"Let us say no more about them," said Nomerfide, "and see to whom Geburon will give his vote."

"I shall give it," said he, "to Madame Oisille, that she may tell us something to the credit of Holy Church." (12)

12 In lieu of this phrase, the De Thou MS. of the Heptameron gives the following: "To make amends for his fault, if fault there were in laying bare the wretched and abominable life of a wicked Churchman, so as to put others on their guard against the hypocrisy of those resembling him, Geburon, who held Madame Oysille in high esteem, as one should hold a lady of discretion, who was no less reluctant to speak evil than prompt to praise and publish the worth which she knew to exist in others, gave her his vote, begging her to tell something to the honour of our holy religion."—L.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.