Elisor Showing the Queen Her Own Image

The Heptameron - Day 3 - Tale 24- Elisor Showing the Queen Her Own Image

TALE XXIV.

Elisor, having unwisely ventured to discover his love to the Queen of Castile, was by her put to the test in so cruel a fashion that he suffered sorely, yet did he reap advantage therefrom.

In the household of the King and Queen of Castile, (1) whose names shall not be mentioned, there was a gentleman of such perfection in all qualities of mind and body, that his like could not be found in all the Spains. All wondered at his merits, but still more at the strangeness of his temper, for he had never been known to love or have connection with any lady. There were very many at Court that might have set his icy nature afire, but there was not one among them whose charms had power to attract Elisor; for so this gentleman was called.

1 M. Lacroix conjectures that the sovereigns referred to are Ferdinand and Isabella, but this appears to us a baseless supposition. The conduct of the Queen in the story is in no wise in keeping with what we know of Isabella's character. Queen Margaret doubtless heard this tale during her sojourn in Spain in 1525. We have consulted many Spanish works, and notably collections of the old ballads, in the hope of being able to throw some light on the incidents related, but have been no more successful than previous commentators.—Ed.

The Queen, who was a virtuous woman but by no means free from that flame which proves all the fiercer the less it is perceived, was much astonished to find that this gentleman loved none of her ladies; and one day she asked him whether it were possible that he could indeed love as little as he seemed to do.

He replied that if she could look upon his heart as she did his face, she would not ask him such a question. Desiring to know his meaning, she pressed him so closely that he confessed he loved a lady whom he deemed the most virtuous in all Christendom. The Queen did all that she could by entreaties and commands to find out who the lady might be, but in vain; whereupon, feigning great wrath, she vowed that she would never speak to him any more if he did not tell her the name of the lady he so dearly loved. At this he was greatly disturbed, and was constrained to say that he would rather die, if need were, than name her.

Finding, however, that he would lose the Queen's presence and favour in default of telling her a thing in itself so honourable that it ought not to be taken in ill part by any one, he said to her in great fear—

"I cannot and dare not tell you, madam, but the first time you go hunting I will show her to you, and I feel sure that you will deem her the fairest and most perfect lady in the world."

This reply caused the Queen to go hunting sooner than she would otherwise have done.

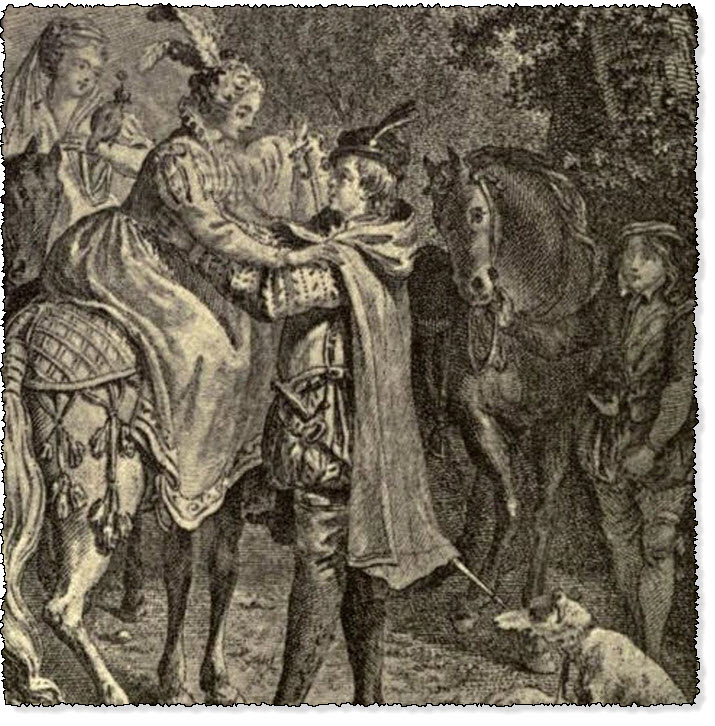

Elisor, having notice of this, made ready to attend her as was his wont, and caused a large steel mirror after the fashion of a corselet to be made for him, which he placed upon his breast and covered with a cloak of black frieze, bordered with purflew and gold braid. He was mounted on a coal-black steed, well caparisoned with everything needful to the equipment of a horse, and such part of this as was metal was wholly of gold, wrought with black enamel in the Moorish style. (2)

2 Damascened.—Ed.

His hat was of black silk, and to it was fastened a rich medal on which by way of device was engraved the god of Love subdued by Force, the whole enriched with precious stones. His sword and dagger were no less handsomely and choicely ordered. In a word, he was most bravely equipped, while so skilled was his horsemanship that all who saw him left the pleasures of the chase to watch the leaps and paces of his steed.

Heptameron Story 24

After bringing the Queen in this fashion to the place where the nets were spread, he dismounted from his noble horse and went to assist the Queen to alight from her palfrey. And whilst she was stretching out her hands to him, he threw his cloak back from before his breast, and taking her in his arms, showed her his corselet-mirror, saying—

"I pray you, madam, look here."

Then, without waiting for her reply, he set her down gently upon the ground.

When the hunt was over, the Queen returned to the castle without speaking to Elisor, but after supper she called him to her and told him that he was the greatest liar she had ever seen; for he had promised to show her at the hunt the lady whom he loved the best, but had not done so, for which reason she was resolved to hold him in esteem no more.

Elisor, fearing that the Queen had not understood the words he had spoken to her, answered that he had indeed obeyed her, for he had shown her not merely the woman but the thing also, that he loved best in all the world.

Pretending that she did not understand him, she replied that he had not, to her knowledge, shown her a single one among her ladies.

"That is true, madam," said Elisor, "but what did I show you when I helped you off your horse?"

"Nothing," said the Queen, "except a mirror on your breast."

"And what did you see in the mirror?" said Elisor.

"I saw nothing but myself," replied the Queen.

"Then, madam," said Elisor, "I have kept faith with you and obeyed your command. There is not, nor ever will there be, another image in my heart save that which you saw upon my breast. Her alone will I love, reverence and worship, not as a woman merely, but as my very God on earth, in whose hands I place my life or my death, entreating her withal that the deep and perfect affection, which was my life whilst it remained concealed, may not prove my death now that it is discovered. And though I be not worthy that you should look on me or accept me for your lover, at least suffer me to live, as hitherto, in the happy consciousness that my heart has chosen so perfect and so worthy an object for its love, wherefrom I can have no other satisfaction than the knowledge that my love is deep and perfect, seeing that I must be content to love without hope of return. And if, now knowing this great love of mine, you should not be pleased to favour me more than heretofore, at least do not deprive me of life, which for me consists wholly in the delight of seeing you as usual. I now have from you nought but what my utmost need requires, and should I have less, you will have a servant the less, for you will lose the best and most devoted that you have ever had or could ever look to have."

The Queen—whether to show herself other than she really was, or to thoroughly try the love he bore her, or because she loved another whom she would not cast off, or because she wished to hold him in reserve to put him in the place of her actual lover should the latter give her any offence—said to him, with a countenance that showed neither anger nor content—"Elisor, I will not feign ignorance of the potency of love, and say aught to you concerning your foolishness in aiming at so high and hard a thing as the love of me; for I know that man's heart is so little under his own control, that he cannot love or hate at will. But, since you have concealed your feelings so well, I would fain know how long it is since you first entertained them."

Elisor, gazing at her beauteous face and hearing her thus inquire concerning his sickness, hoped that she might be willing to afford him a remedy. But at the same time, observing the grave and staid expression of her countenance, he became afraid, feeling himself to be in the presence of a judge whose sentence, he suspected, would be against him. Nevertheless he swore to her that this love had taken root in his heart in the days of his earliest youth, though it was only during the past seven years that it had caused him pain,—and yet, in truth, not pain, but so pleasing a sickness that its cure would be his death.

"Since you have displayed such lengthened steadfastness," said the Queen, "I must not show more haste in believing you, than you have shown in telling me of your affection. If, therefore, it be as you say, I will so test your sincerity that I shall never afterwards be able to doubt it; and having proved your pain, I will hold you to be towards me such as you yourself swear you are; and on my knowing you to be what you say, you, for your part, shall find me to be what you desire."

Elisor begged her to test him in any way she pleased, there being nothing, he said, so difficult that it would not appear very easy to him, if he might have the honour of proving his love to her; and accordingly he begged her once more to command him as to what she would to have him do.

"Elisor," she replied, "if you love me as much as you say, I am sure that you will deem nothing hard of accomplishment if only it may bring you my favour. I therefore command you, by your desire of winning it and your fear of losing it, to depart hence to-morrow morning without seeing me again, and to repair to some place where, until this day seven years, you shall hear nothing of me nor I anything of you. You, who have had seven years' experience of this love, know that you do indeed love me; and when I have had a like experience, I too shall know and believe what your words cannot now make me either believe or understand."

When Elisor heard this cruel command, he on the one hand suspected that she desired to remove him from her presence, yet, on the other, he hoped that this proof would plead more eloquently for him than any words he could utter. He therefore submitted to her command, and said—

"For seven years I have lived hopeless, bearing in my breast a hidden flame; now, however, that this is known to you, I shall spend these other seven years in patience and trust. But, madam, while I obey your command, which robs me of all the happiness that I have heretofore had in the world, what hope will you give me that at the end of the seven years you will accept me as your faithful and devoted lover?"

"Here is a ring," said the Queen, drawing one from her finger, "which we will cut in two. I will keep one half, and you shall keep the other, (3) so that I may know you by this token, if the lapse of time should cause me to forget your face."

3 This was a common practice at the time between lovers, and even between husbands and wives. There is the familiar but doubtful story of Frances de Foix, Countess of Châteaubriant, who became Francis I.'s mistress, and who is said to have divided a ring in this manner with her husband, it being understood between them that she was not to repair to Court, or even leave her residence in Brittany, unless her husband sent her as a token the half of the ring which he had kept. Francis I., we are told, heard of this, and causing a ring of the same pattern to be made, he sent half of it to the Countess, who thereupon came to Court, imagining that it was her husband who summoned her. Whether the story be true or not, it should be mentioned that the sole authority for it is Varillas, whose errors and inventions are innumerable.—Ed.

Elisor took the ring and broke it in two, giving one half of it to the Queen, and keeping the other himself. Then, more corpse-like than those who have given up the ghost, he took his leave, and went to his lodging to give orders for his departure. In doing this he sent all his attendants to his house, and departed alone with one servingman to so solitary a spot that none of his friends or kinsfolk could obtain tidings of him during the seven years.

Of the life that he led during this time, and the grief that he endured through this banishment, nothing is recorded, but lovers cannot be ignorant of their nature. At the end of the seven years, just as the Queen was one day going to mass, a hermit with a long beard came to her, kissed her hand, and presented her with a petition. This she did not look at immediately, although it was her custom to receive in her own hands all the petitions that were presented to her, no matter how poor the petitioners might be.

When mass was half over, however, she opened the petition, and found in it the half-ring which she had given to Elisor. At this she was not less glad than astonished, and before reading the contents she instantly commanded her almoner to bring her the tall hermit who had presented her the petition.

The almoner looked for him everywhere, but could obtain no tidings of him, except that some one said that he had seen him mount a horse, but knew not what road he had taken.

Whilst she was waiting for the almoner's return, the Queen read the petition, which she found to be an epistle in verse, written in the best style imaginable; and were it not that I would have you acquainted with it, I should never have dared to translate it; for you must know, ladies, that, for grace and expression, the Castilian is beyond compare the tongue which is best fitted to set forth the passion of love. The matter of the letter was as follows:—

"Time, by his puissance stern, his sov'reign might, Hath made me learn love's character aright; And, bringing with him, in his gloomy train, The speechless eloquence of bitter pain, Hath caused the unbelieving one to know What words of love were impotent to show. Time made my heart, aforetime, meekly bow Unto the mastery of love; but now Time hath, at last, revealed love to be Far other than it once appeared to me; And Time the frail foundation hath made clear Whereon I purposed, once, my love to rear— To wit, your beauty, which but served as sheath To hide the cruelty that lurked beneath. Yea, Time hath shown me beauty's nothingness And taught me e'en your cruelty to bless, That cruelty which banished me the place Where I, at least, had gazed upon your face. And when no more I saw your beauty beam The harsher yet your cruelty did seem; Yet in obedience failed I not, and this Hath been the means of compassing my bliss. For Time, love's parent, pitiful at last, Upon my woe commiserate eyes hath cast, And done to me so excellent a turn, That, if I now come back, think not I yearn To sigh and dally, and renew the spell— I only come to bid a last farewell. Time, the revealer, hath not failed to prove How base and sorry is all human love, So that through Time, I now that time regret When all my fancy upon love was set, For then Time wasted was, lost in love's chains, Sorrow whereof is all that now remains. And Time in teaching me that love's deceit Hath brought another, far more pure and sweet, To dwell within me, in the lonely spot Where tears and silence long have been my lot. Time, to my heart, that higher love hath brought With which the lower can no more be sought; Time hath the latter into exile driven, And, to the first, myself hath wholly given, And consecrated to its service true The heart and hand I erst had given to you. When I was yours you nothing showed of grace, And I that nothing loved, for your fair face; Then, death for loyalty, you sought to give, And I, in fleeing it, have learnt to live. For, by the tender love that Time hath brought The other vanquished is, and turned to nought; Once did it lure and lull me, but I swear It now hath wholly vanished in thin air. And so your love and you I gladly leave, And, needing neither, will forbear to grieve; The other perfect, lasting love is mine, To it I turn, nor for the lost one pine. My leave I take of cruelty and pain, Of hatred, bitter torment, cold disdain, And those hot flames which fill you, and which fire Him, that beholds your beauty, with desire. Nor can I better part from ev'ry throe, From ev'ry evil hap, and stress of woe, And the fierce passion of love's awful hell, Than by this single utterance: Farewell. Learn therefore, that whate'er may be in store, Each other's faces we shall see no more."

This letter was not read without many tears and much astonishment on the Queen's part, together with regret surpassing belief; for the loss of a lover filled with so perfect a love must needs have been keenly felt; and not all her treasures, nor even her kingdom itself, could hinder the Queen from being the poorest and most wretched lady in the world, seeing that she had lost that which all the world's wealth could not replace. And having heard mass to the end and returned to her apartment, she there made such mourning as her cruelty had provoked. And there was not a mountain, a rock or a forest to which she did not send in quest of the hermit; but He who had withdrawn him out of her hands preserved him from falling into them again, and took him away to Paradise before she could gain tidings of him in this world.

"This instance shows that a lover should never acknowledge that which may do him harm and in no wise help him. And still less, ladies, should you in your incredulity demand so hard a test, lest in getting your proof you lose your lover."

"Truly, Dagoucin," said Geburon, "I had all my life long deemed the lady of your story to be the most virtuous in the world, but now I hold her for the most cruel woman that ever lived."

"Nevertheless," said Parlamente, "it seems to me that she did him no wrong in wishing to try him for seven years, in order to see whether he did love her as much as he said. Men are so wont to speak falsely in these matters that before trusting them, if indeed one trust them at all, one cannot put them to the proof too long."

"The ladies of our day," said Hircan, "are far wiser than those of past times, for they are as sure of a lover after a seven days' trial as the others were after seven years."

"Yet there are those in this company," said Longarine, "who have been loved with all earnestness for seven years and more, and albeit have not been won."

"'Fore God," said Simontault, "you speak the truth; but such as they ought to be ranked with the ladies of former times, for they cannot be recognised as belonging to the present."

"After all," said Oisille, "the gentleman was much beholden to the lady, for it was owing to her that he devoted his heart wholly to God."

"It was very fortunate for him," said Saffredent, "that he found God upon the way, for, considering the grief he was in, I am surprised that he did not give himself to the devil."

"And did you give yourself to such a master," asked Ennasuite, "when your lady ill used you?"

"Yes, thousands of times," said Saffredent, "but the devil, seeing that all the torments of hell could bring me no more suffering than those which she caused me to endure, never condescended to take me. He knew full well that no devil is so bad as a lady who is deeply loved and will make no return."

"If I were you," said Parlamente to Saffredent, "and held such an opinion as that, I would never make love to woman."

"My affection," said Saffredent, "and my folly are always so great, that where I cannot command I am well content to serve. All the ill-will of the ladies cannot subdue the love that I bear them. But, I pray you, tell me on your conscience, do you praise this lady for such great harshness?"

"Ay," said Oisille, "I do, for I think that she wished neither to receive love nor to bestow it."

"If such was her mind," said Simontault, "why did she hold out to him the hope of being loved after the seven years were past?"

"I am of your opinion," said Longarine, "for ladies who are unwilling to love give no occasion for the continuance of the love that is offered them."

"Perhaps," said Nomerfide, "she loved some one else less worthy than that honourable gentleman, and so forsook the better for the worse."

"'T faith," said Saffredent, "I think that she meant to keep him in readiness and take him whenever she might leave the other whom for the time she loved the best."

"I can see," said Oisille, (4) "that the more we talk in this way, the more those who would not be harshly treated will do their utmost to speak ill of us. Wherefore, Dagoucin, I pray you give some lady your vote."

4 Prior to this sentence the following passage occurs in the De Thou MS.: "When Madame Oysille saw that the men, under pretence of censuring the Queen of Castille for conduct which certainly cannot be praised either in her or in any other, continued saying so much evil of women, that the most discreet and virtuous were spared no more than the most foolish and wanton, she could endure it no longer, but spoke and said," &c.—L.

"I give it," he said, "to Longarine, for I feel sure that she will tell us no melancholy story, and that she will speak the truth without sparing man or woman."

"Since you deem me so truthful," said Longarine, "I will be so bold as to relate an adventure that befel a very great Prince, who surpasses in worth all others of his time. Lying and dissimulation are, indeed, things not to be employed save in cases of extreme necessity; they are foul and infamous vices, more especially in Princes and great lords, on whose lips and features truth sits more becomingly than on those of other men. But no Prince in the world however great he be, even though he have all the honours and wealth he may desire, can escape being subject to the empire and tyranny of Love; indeed it would seem that the nobler and more high-minded the Prince, the more does Love strive to bring him under his mighty hand. For this glorious God sets no store by common things; his majesty rejoices solely in the daily working of miracles, such as weakening the strong, strengthening the weak, giving knowledge to the simple, taking intelligence from the most learned, favouring the passions, and overthrowing the reason. In such transformations as these does the Deity of Love delight. Now since Princes are not exempt from love's thraldom, so also are they not free from its necessities, and must therefore perforce be permitted to employ falsehood, hypocrisy and deceit, which, according to the teaching of Master Jehan de Mehun, (5) are the means to be employed for vanquishing our enemies. And, since such conduct is praiseworthy on the part of a Prince in such a case as this (though in any other it were deserving of blame), I will relate to you the devices to which a young Prince resorted, and by which he contrived to deceive those who are wont to deceive the whole world."

5 John dc Melun, who continued the Roman de la Rose begun by Lorris.—D.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.