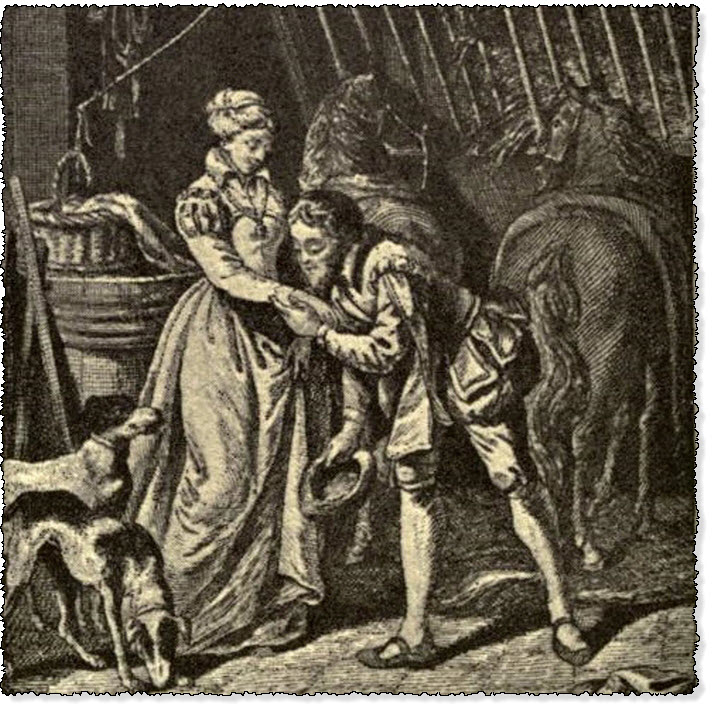

the Lord of Avannes Paying his Court in Disguise

The Heptameron - Day 3, Tale 26 - the Lord of Avannes Paying his Court in Disguise

TALE XXVI.

By the counsel and sisterly affection of a virtuous lady, the Lord of Avannes was drawn from the wanton love that he entertained for a gentlewoman dwelling at Pampeluna.

In the days of King Louis the Twelfth there lived a young lord called Monsieur d'Avannes, (1) son of the Lord of Albret [and] brother to King John of Navarre, with whom this aforesaid Lord of Avannes commonly abode.

1 This is Gabriel d'Albret, Lord of Avesnes and Lesparre, fourth son of Alan the Great, Sire d'Albret, and brother of John d'Albret, King of Navarre, respecting whom see post, note 4 to Tale XXX. Queen Margaret is in error in dating this story from the reign of Louis XII. The incidents she relates must have occurred between 1485 and 1490, under the reign of Charles VIII., by whom Gabriel d'Albret, on reaching manhood, was successively appointed counsellor and chamberlain, Seneschal of Guyenne and Viceroy of Naples. Under Louis XII. he took a prominent part in the Italian campaigns of 1500-1503, in which latter year he is known to have made his will, bequeathing all he possessed to his brother, Cardinal d'Albret. He died a bachelor in 1504.—See Anselme's Histoire Généalogique, vol. vi. p. 214.—L. and Ed.

Now this young lord, who was fifteen years of age, was so handsome and so fully endowed with every excellent grace that he seemed to have been made solely to be loved and admired, as he was indeed by all who saw him, and above all by a lady who dwelt in the town of Pampeluna (2) in Navarre. She was married to a very rich man, with whom she lived in all virtue, inasmuch that, although her husband was nearly fifty years old and she was only three and twenty, she dressed so plainly that she had more the appearance of a widow than of a married woman. Moreover, she was never known to go to weddings or feasts unless accompanied by her husband, whose worth and virtue she prized so highly that she set them before all the comeliness of other men. And her husband, finding her so discreet, trusted her and gave all the affairs of his household into her hands.

2 Pampeluna or Pamplona, the capital of Navarre, wrested from King John in 1512 by the troops of Ferdinand the Catholic.—Ed.

One day this rich man was invited with his wife to a wedding among their kinsfolk; and among those who were present to do honour to the bridal was the young Lord of Avannes, who was exceedingly fond of dancing, as was natural in one who surpassed therein all others of his time. When dinner was over and the dances were begun, the rich man begged the Lord of Avannes to do his part, whereupon the said lord asked him with whom he would have him dance.

"My lord," replied the gentleman, "I can present to you no lady fairer and more completely at my disposal than my wife, and I therefore beg you to honour me so far as to lead her out."

This the young Prince did; and he was still so young that he took far greater pleasure in frisking and dancing than in observing the beauty of the ladies. But his partner, on the contrary, gave more heed to his grace and beauty than to the dance, though in her prudence she took good care not to let this appear.

The supper hour being come, the Lord of Avannes bade the company farewell, and departed to the castle, (3) whither the rich man accompanied him on his mule. And as they were going, the rich man said to him—

"My lord, you have this day done so much honour to my kinsfolk and to me, that I should indeed be ungrateful if I did not place myself with all that belongs to me at your service. I know, sir, that lords like yourself, who have stern and miserly fathers, are often in greater need of money than we, who, with small establishments and careful husbandry, seek only to save up wealth. Now, albeit God has given me a wife after my own heart, it has not pleased Him to give me all my Paradise in this world, for He has withheld from me the joy that fathers derive from having children. I know, my lord, that it is not for me to adopt you as a son, but if you will accept me for your servant and make known to me your little affairs, I will not fail to assist you in your need so far as a hundred thousand crowns may go."

3 Evidently the castle of Pampeluna, where Gabriel d'Albret resided with his brother the King.—Ed.

The Lord of Avannes was in great joy at this offer, for he had just such a father as the other had described; accordingly he thanked him, and called him his adopted father.

From that hour the rich man evinced so much love towards the Lord of Avannes, that morning and evening he failed not to inquire whether he had need of anything, nor did he conceal this devotion from his wife, who loved him for it twice as much as before. Thenceforward the Lord of Avannes had no lack of anything that he desired. He often visited the rich man, and ate and drank with him; and when he found the husband abroad, the wife gave him all that he required, and further spoke to him so sagely, exhorting him to live discreetly and virtuously, that he reverenced and loved her above all other women.

Having God and honour before her eyes, she remained content with thus seeing him and speaking to him, for these are sufficient for virtuous and honourable love; and she never gave any token whereby he might have imagined that she felt aught but a sisterly and Christian affection towards him.

While this secret love continued, the Lord of Avannes, who, by the assistance that I have spoken of, was always well and splendidly apparelled, came to the age of seventeen years, and began to frequent the company of ladies more than had been his wont. And although he would fain have loved this virtuous lady rather than any other, yet his fear of losing her friendship should she hear any such discourse from him, led him to remain silent and to divert himself elsewhere.

He therefore addressed himself to a gentlewoman of the neighbourhood of Pampeluna, who had a house in the town, and was married to a young man whose chief delight was in horses, hawks and hounds. For her sake, he began to set on foot a thousand diversions, such as tourneys, races, wrestlings, masquerades, banquets, and other pastimes, at all of which this young lady was present. But as her husband was very humorsome, and her parents, knowing her to be both fair and frolicsome, were jealous of her honour, they kept such strict watch over her that my Lord of Avannes could obtain nothing from her save a word or two at the dance, although, from the little that had passed between them, he well knew that time and place alone were wanting to crown their loves.

He therefore went to his good father, the rich man, and told him that he deeply desired to make a pilgrimage to our Lady of Montferrat, (4) for which reason he begged him to house his followers, seeing that he wished to go alone.

4 The famous monastery of Montserrate, at eight leagues from Barcelona, where is preserved the ebony statue of the Virgin carrying the Infant Jesus, which is traditionally said to have been carved by St. Luke, and to have been brought to Spain by St. Peter.—See Libro de la historia y milagros hechos à invocation de Nuestra Seilora de Montserrate, Barcelona, 1556, 8vo.—Ed.

To this the rich man agreed; but his wife, in whose heart was that great soothsayer, Love, forthwith suspected the true nature of the journey, and could not refrain from saying—

"My lord, my lord, the Lady you adore is not without the walls of this town, so I pray that you will have in all matters a care for your health."

At this he, who both feared and loved her, blushed so deeply that, without speaking a word, he confessed the truth; and so he went away.

Having bought a couple of handsome Spanish horses, he dressed himself as a groom, and disguised his face in such a manner that none could know him. The gentleman who was husband to the wanton lady, and who loved horses more than aught beside, saw the two that the Lord of Avannes was leading, and forthwith offered to buy them. When he had done so, he looked at the groom, who was managing the horses excellently well, and asked whether he would enter his service. The Lord of Avannes replied that he would; saying that he was but a poor groom, who knew no trade except the caring of horses, but in this he could do so well that he would assuredly give satisfaction. At this the gentleman was pleased, and having given him the charge of all his horses, entered his house, and told his wife that he was leaving for the castle, and confided his horses and groom to her keeping.

The lady, as much to please her husband as for her own diversion, went to see the horses, and looked at the new groom, who seemed to her to be well favoured, though she did not at all recognise him. Seeing that he was not recognised, he came up to do her reverence in the Spanish fashion and kissed her hand, and, in doing so, pressed it so closely that she at once knew him, for he had often done the same at the dance. From that moment, the lady thought of nothing but how she might speak to him in private; and contrived to do so that very evening, for, being invited to a banquet, to which her husband wished to take her, she pretended that she was ill and unable to go.

The husband, being unwilling to disappoint his friends, thereupon said to her—

"Since you will not come, my love, I pray you take good care of my horses and hounds, so that they may want for nothing."

The lady deemed this charge a very agreeable one, but, without showing it, she replied that since he had nothing better for her to do, she would show him even in these trifling matters how much she desired to please him.

And scarcely was her husband outside the door than she went down to the stable, where she found that something was amiss, and to set it right gave so many orders to the serving-men on this side and the other, that at last she was left alone with the chief groom, when, fearing that some one might come upon them, she said to him—

"Go into the garden, and wait for me in a summer house that stands at the end of the alley."

This he did, and with such speed that he stayed not even to thank her.

When she had set the whole stable in order, she went to see the dogs, and was so careful to have them properly treated, that from mistress she seemed to have become a serving-woman. Afterwards she withdrew to her own apartment, where she lay down weariedly upon the bed, saying that she wished to rest. All her women left her excepting one whom she trusted, and to whom she said—

"Go into the garden, and bring here the man whom you will find at the end of the alley."

The maid went and found the groom, whom she forthwith brought to the lady, and the latter then sent her outside to watch for her husband's return. When the Lord of Avannes found himself alone with the lady, he doffed his groom's dress, took off his false nose and beard, and, not like a timorous groom, but like the handsome lord he was, boldly got into bed with her without so much as asking her leave; and he was received as the handsomest youth of his time deserved to be by the handsomest and gayest lady in the land, and remained with her until her husband returned. Then he again took his mask and left the place which his craft and artifice had usurped.

On entering the courtyard the gentleman heard of the diligence that his wife had shown in obeying him, and he thanked her heartily for it.

"Sweetheart," said the lady, "I did but my duty. Tis true that if we did not keep watch upon these rogues of servants you would not have a dog without the mange or a horse in good condition; but, now that I know their slothfulness and your wishes, you shall be better served than ever you were before."

The gentleman, who thought that he had chosen the best groom in the world, asked her what she thought of him.

"I will own, sir," she replied, "that he does his work as well as any you could have chosen, but he needs to be urged on, for he is the sleepiest knave I ever saw."

So the lord and his lady lived together more lovingly than before, and he lost all the suspicion and jealousy with which he had regarded her, seeing that she was now as careful of her house hold as she had formerly been devoted to banquets, dances and assemblies. Whereas, also, she had formerly been wont to spend four hours in attiring herself, she was now often content to wear nothing but a dressing-gown over her chemise; and for this she was praised by her husband and by every one else, for they did not understand that a stronger devil had entered her and thrust out a weaker one.

Thus did this young lady, under the guise of a virtuous woman, like the hypocrite she was, live in such wantonness that reason, conscience, order and moderation found no place within her. The youth and tender constitution of the Lord of Avannes could not long endure this, and he began to grow so pale and lean that even without his mask he might well have passed unrecognised; yet the mad love that he had for this woman so blunted his understanding that he imagined he had strength to accomplish feats that even Hercules had tried in vain. However, being at last constrained by sickness and advised thereto by his lady, who was not so fond of him sick as sound, he asked his master's leave to return home, and this his master gave him with much regret, making him promise to come back to service when he was well again.

In this wise did the Lord of Avannes go away, and all on foot, for he had only the length of a street to travel. On arriving at the house of his good father, the rich man, he there found only his wife, whose honourable love for him had been in no whit lessened by his journey. But when she saw him so colourless and thin, she could not refrain from saying to him—

"I do not know, my lord, how your conscience may be, but your body has certainly not been bettered by your pilgrimage. I fear me that your journeyings by night have done you more harm than your journeyings by day, for had you gone to Jerusalem on foot you would have come back more sunburnt, indeed, but not so thin and weak. Pay good heed to this one, and worship no longer such images as those, which, instead of reviving the dead, cause the living to die. I would say more, but if your body has sinned it has been well punished, and I feel too much pity for you to add any further distress."

When my Lord of Avannes heard these words, he was as sorry as he was ashamed.

"Madam," he replied, "I have heard that repentance follows upon sin, and now I have proved it to my cost. But I pray you pardon my youth, which could not have been punished save by the evil in which it would not believe."

Thereupon changing her discourse, the lady made him lie down in a handsome bed, where he remained for a fortnight, taking nothing but restoratives; and the lady and her husband constantly kept him company, so that he always had one or the other beside him. And although he had acted foolishly, as you have heard, contrary to the desire and counsel of the virtuous lady, she, nevertheless, lost nought of the virtuous love that she felt towards him, for she still hoped that, after spending his early youth in follies, he would throw them off and bring himself to love virtuously, and so be all her own.

During the fortnight that he was in her house, she held to him such excellent discourse, all tending to the love of virtue, that he began to loathe the folly that he had committed. Observing, moreover, the lady's beauty, which surpassed that of the wanton one, and becoming more and more aware of the graces and virtues that were in her, he one day, when it was rather dark, could not longer hold from speaking, but, putting away all fear, said to her—

"I see no better means, madam, for becoming a virtuous man such as you urge me and desire me to be, than by being heart and soul in love with virtue. I therefore pray you, madam, to tell me whether you will give me in this matter all the assistance and favour that you can."

The lady rejoiced to find him speaking in this way, and replied—

"I promise you, my lord, that if you are in love with virtue as it beseems a lord like yourself to be, I will assist your efforts with all the strength that God has given me."

"Now, madam," said my Lord of Avannes, "remember your promise, and consider also that God, whom man knows by faith alone, deigned to take a fleshly nature like that of the sinner upon Himself, in order that, by drawing our flesh to the love of His humanity, He might at the same time draw our spirits to the love of His divinity, thus making use of visible means to make us in all faith love the things which are invisible. In like manner this virtue, which I would fain love all my life long, is a thing invisible except in so far as it produces outward effects, for which reason it must take some bodily shape in order to become known among men. And this it has done by clothing itself in your form, the most perfect it could find. I therefore recognise and own that you are not only virtuous but virtue itself; and now, finding it shine beneath the veil of the most perfect person that was ever known, I would fain serve it and honour it all my life, renouncing for its sake every other vain and vicious love."

The lady, who was no less pleased than surprised to hear these words, concealed her happiness and said—

"My lord, I will not undertake to answer your theology, but since I am more ready to apprehend evil than to believe in good, I will entreat you to address to me no more such words as lead you to esteem but lightly those who are wont to believe them. I very well know that I am a woman like any other and imperfect, and that virtue would do a greater thing by transforming me into itself than by assuming my form—unless, indeed, it would fain pass unrecognised through the world, for in such a garb as mine its real nature could never be known. Nevertheless, my lord, with all my imperfections, I have ever borne to you all such affection as is right and possible in a woman who reverences God and her honour. But this affection shall not be declared until your heart is capable of that patience which a virtuous love enjoins. At that time, my lord, I shall know what to say, but meanwhile be assured that you do not love your own welfare, person and honour as I myself love them."

Heptameron Story 26

The Lord of Avannes timorously and with tears in his eyes entreated her earnestly to seal her words with a kiss, but she refused, saying that she would not break for him the custom of her country.

While this discussion was going on the husband came in, and my Lord of Avannes said to him—

"I am greatly indebted, father, both to you and to your wife, and I pray you ever to look upon me as your son."

This the worthy man readily promised.

"And to seal your love," said the Lord of Avannes, "I pray you let me kiss you." This he did, after which the Lord of Avannes said—:

"If I were not afraid of offending against the law, I would do the same to your wife and my mother."

Upon this, the husband commanded his wife to kiss him, which she did without appearing either to like or to dislike what her husband commanded her. But the fire that words had already kindled in the poor lord's heart, grew fiercer at this kiss which had been so earnestly sought for and so cruelly denied.

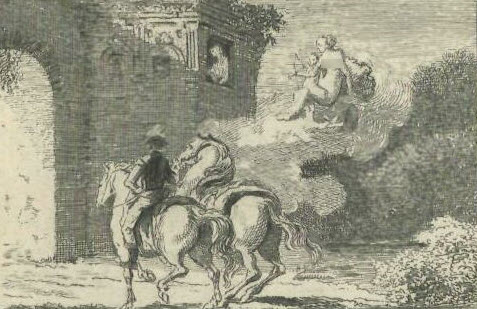

After this the Lord of Avannes betook himself to the castle to see his brother, the King, to whom he told fine stories about his journey to Montferrat. He found that the King was going to Oly and Taffares, (5) and, reflecting that the journey would be a long one, he fell into deep sadness, and resolved before going away to try whether the virtuous lady were not better disposed towards him than she appeared to be.

5 Evidently Olite and Tafalla, the former at thirty and the latter at twenty-seven miles from Pamplona. The two towns were commonly called la flor de Navarra. King John doubtless intended sojourning at the summer palaces which his predecessor Carlos the Noble had built at either locality, and which were connected, it is said, by a gallery a league in length. Some ruins of these palaces still exist. —Ed.

He therefore went to lodge in the street in which she lived, where he hired an old house, badly built of timber. About midnight he set fire to it, and the alarm, which spread through the whole town, reached the rich man's house. He asked from the window where the fire was, and hearing that it was in the house of the Lord of Avannes, immediately hastened thither with all his servants. He found the young lord in the street, clad in nothing but his shirt, whereat in his deep compassion he took him in his arms, and, covering him with his own robe, brought him home as quickly as possible, where he said to his wife, who was in bed—

"Here, sweetheart, I give this prisoner into your charge. Treat him as you would treat myself."

As soon as he was gone, the Lord of Avannes, who would gladly have been treated like a husband, sprang lightly into the bed, hoping that place and opportunity would bring this discreet lady to a different mind; but he found the contrary to be the case, for as he leaped into the bed on one side, she got out at the other. Then, putting on her dressing-gown, she came up to the head of the bed and spoke as follows—

"Did you think, my lord, that opportunity could influence a chaste heart? Nay, just as gold is tried in the furnace, so a chaste heart becomes stronger and more virtuous in the midst of temptation, and grows colder the more it is assailed by its opposite. You may be sure, therefore, that had I been otherwise minded than I professed myself to be, I should not have wanted means, to which I have paid no heed solely because I desire not to use them. So I beg of you, if you would have me preserve my affection for you, put away not merely the desire but even the thought that you can by any means whatever make me other than I am."

While she was speaking, her women came in, and she commanded a collation of all kinds of sweetmeats to be brought; but the young lord could neither eat nor drink, in such despair was he at having failed in his enterprise, and in such fear lest this manifestation of his passion should cost him the familiar intercourse that he had been wont to have with her.

Having dealt with the fire, the husband came back again, and begged the Lord of Avannes to remain at his house for the night. This he did, but in such wise that his eyes were more exercised in weeping than in sleeping. Early in the morning he went to bid them farewell, while they were still in bed; and in kissing the lady he perceived that she felt more pity for the offence than anger against the offender, and thus was another brand added to the fire of his love. After dinner, he set out for Taffares with the King; but before leaving he went again to take yet another farewell of his good father and the lady who, after her husband's first command, made no difficulty in kissing him as her son.

But you may be sure that the more virtue prevented her eyes and features from testifying to the hidden flame, the fiercer and more intolerable did that flame become. And so, being unable to endure the war between love and honour, which was waging in her heart, but which she had nevertheless resolved should never be made apparent, and no longer having the comfort of seeing and speaking to him for whose sake alone she cared to live, she fell at last into a continuous fever, caused by a melancholic humour which so wrought upon her that the extremities of her body became quite cold, while her inward parts burned without ceasing. The doctors, who have not the health of men in their power, began to grow very doubtful concerning her recovery, by reason of an obstruction that affected the extremities, and advised her husband to admonish her to think of her conscience and remember that she was in God's hands—as though indeed the healthy were not in them also.

The husband, who loved his wife devotedly, was so saddened by their words that for his comfort he wrote to the Lord of Avannes entreating him to take the trouble to come and see them, in the hope that the sight of him might be of advantage to the patient. On receiving the letter, the Lord of Avannes did not tarry, but started off post-haste to the house of his worthy father, where he found the servants, both men and women, assembled at the door, making such lament for their mistress as she deserved.

So greatly amazed was he at the sight, that he remained on the threshold like one paralysed, until he beheld his good father, who embraced him, weeping the while so bitterly that he could not utter a word. Then he led the Lord of Avannes to the chamber of the sick lady, who, turning her languid eyes upon him, put out her hand and drew him to her with all the strength she had. She kissed and embraced him, and made wondrous lamentation, saying—

"O my lord, the hour has come when all dissimulation must cease, and I must confess the truth which I have been at such pains to hide from you. If your affection for me was great, know that mine for you has been no less; but my grief has been greater than yours, because I have had the anguish of concealing it contrary to the wish of my heart. God and my honour have never, my lord, suffered me to make it known to you, lest I should increase in you that which I sought to diminish; but you must learn that the 'no' I so often said to you pained me so greatly in the utterance that it has indeed proved the cause of my death.

"Nevertheless, I am glad it should be so, and that God in His grace should have caused me to die before the vehemence of my love has stained my conscience and my fair fame; for smaller fires have ere now destroyed greater and stronger structures. And I am glad that before dying I have been able to make known to you that my affection is equal to your own, save only that men's honour and women's are not the same thing. And I pray you, my lord, fear not henceforward to address yourself to the greatest and most virtuous of ladies; for in such hearts do the deepest and discreetest passions dwell, and moreover, your own grace and beauty and worth will not suffer your love to toil without reward.

"I will not beg you, my lord, to pray God for me, because I know full well that the gate of Paradise is never closed against true lovers, and that the fire of love punishes lovers so severely in this life here that they are forgiven the sharp torment of Purgatory. And now, my lord, farewell; I commend to you your good father, my husband. Tell him the truth as you have heard it from me, that he may know how I have loved God and him. And come no more before my eyes, for I now desire to think only of obtaining those promises made to me by God before the creation of the world."

With these words she kissed him and embraced him with all the strength of her feeble arms. The young lord, whose heart was as nearly dead through pity as hers was through pain, was unable to say a single word. He withdrew from her sight to a bed that was in the room, and there several times swooned away.

Then the lady called her husband, and, after giving him much virtuous counsel, commended the Lord of Avannes to him, declaring that next to himself she had loved him more than any one upon earth, and so, kissing her husband, she bade him farewell. Then, after the extreme unction, the Holy Sacrament was brought to her from the altar, and this she received with the joy of one who is assured of her salvation. And finding that her sight was growing dim and her strength failing her, she began to utter the "In manus" aloud.

Hearing this cry, the Lord of Avannes raised himself up on the bed where he was lying, and gazing piteously upon her, beheld her with a gentle sigh surrender her glorious soul to Him from whom it had come. When he perceived that she was dead, he ran to the body, which when alive he had ever approached with fear, and kissed and embraced it in such wise that he could hardly be separated from it, whereat the husband was greatly astonished, for he had never believed he bore her so much affection; and with the words, "Tis too much, my lord," he led him away.

After he had lamented for a great while, the Lord of Avannes related all the converse they had had together during their love, and how, until her death, she had never given him sign of aught save severity. This, while it gave the husband exceeding joy, also increased his grief and sorrow at the loss he had sustained, and for the remainder of his days he rendered service to the Lord of Avannes.

But from that time forward my Lord of Avannes, who was then only eighteen years old, went to reside at Court, where he lived for many years without wishing to see or to speak with any living woman by reason of his grief for the lady he had lost; and he wore mourning for her sake during more than ten years. (6)

6 Some extracts from Brantôme bearing on this story will be found in the Appendix, C.

"You here see, ladies, what a difference there is between a wanton lady and a discreet one. The effects of love are also different in each case; for the one came by a glorious and praiseworthy death, while the other lived only too long with the reputation of a vile and shameless woman. Just as the death of a saint is precious in the sight of God, so is the death of a sinner abhorrent."

"In truth, Saffredent," said Oisille, "you have told us the finest tale imaginable, and any one who knew the hero would deem it better still. I have never seen a handsomer or more graceful gentleman than was this Lord of Avannes."

"She was indeed a very virtuous woman," said Saffredent. "So as to appear outwardly more virtuous than she was in her heart, and to conceal her love for this worthy lord which reason and nature had inspired, she must needs die rather than take the pleasure which she secretly desired."

"If she had felt such a desire," said Parlamente, "she would have lacked neither place nor opportunity to make it known; but the greatness of her virtue prevented her desire from exceeding the bounds of reason."

"You may paint her as you will," said Hircan, "but I know very well that a stronger devil always thrusts out the weaker, and that the pride of ladies seeks pleasure rather than the fear and love of God. Their robes are long and well woven with dissimulation, so that we cannot tell what is beneath, for if their honour were not more easily stained than ours, (7) you would find that Nature's work is as complete in them as in ourselves. But not daring to take the pleasure they desire, they have exchanged that vice for a greater, which they deem more honourable, I mean a self-sufficient cruelty, whereby they look to obtain everlasting renown.

7 This reading is borrowed from MS. No. 1520. In the MS. mainly followed for this translation, the passage runs as follows-"if their honour were not more easily stained than their hearts."—L.

By thus glorying in their resistance to the vice of Nature's law—if, indeed, anything natural be vicious—they become not only like inhuman and cruel beasts, but even like the devils whose pride and subtility they borrow." (8)

8 This reading is borrowed from MS. No. 1520. In our MS. the passage runs—"like the devils whose semblance and subtility they borrow."—L.

"Tis a pity," said Nomerfide, "that you should have an honourable wife, for you not only think lightly of virtue, but are even fain to prove that it is vice."

"I am very glad," said Hircan, "to have a wife of good repute, just as I, myself, would be of good repute. But as for chastity of heart, I believe that we are both children of Adam and Eve; wherefore, when we examine ourselves, we have no need to cover our nakedness with leaves, but should rather confess our frailty."

"I know," said Parlamente, "that we all have need of God's grace, being all steeped in sin; but, for all that, our temptations are not similar to yours, and if we sin through pride, no one is injured by it, nor do our bodies and hands receive a stain. But your pleasure consists in dishonouring women, and your honour in slaying men in war—two things expressly contrary to the law of God." (9)

"I admit what you say," said Geburon, "but God has said, 'Whosoever looketh with lust, hath already committed adultery in his heart,' and further, 'Whosoever hateth his neighbour is a murderer.' (10) Do you think that women offend less against these texts than we?"

9 This sentence, defective in our MS., is taken from No. 1520.—L. 10 1 St. John iii. 15.—M.

"God, who judges the heart," said Longarine, "must decide that. But it is an important thing that men should not be able to accuse us, for the goodness of God is so great, that He will not judge us unless there be an accuser. And so well, moreover, does He know the frailty of our hearts, that He will even love us for not having put our thoughts into execution."

"I pray you," said Saffredent, "let us leave this dispute, for it savours more of a sermon than of a tale. I give my vote to Ennasuite, and beg that she will bear in mind to make us laugh."

"Indeed," said she, "I will not fail to do so; for I would have you know that whilst coming hither, resolved upon relating a fine story to you to-day, I was told so merry a tale about two servants of a Princess, that, in laughing at it, I quite forgot the melancholy story which I had prepared, and which I will put off until to-morrow; for, with the merry face I now have, you would scarce find it to your liking."

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.