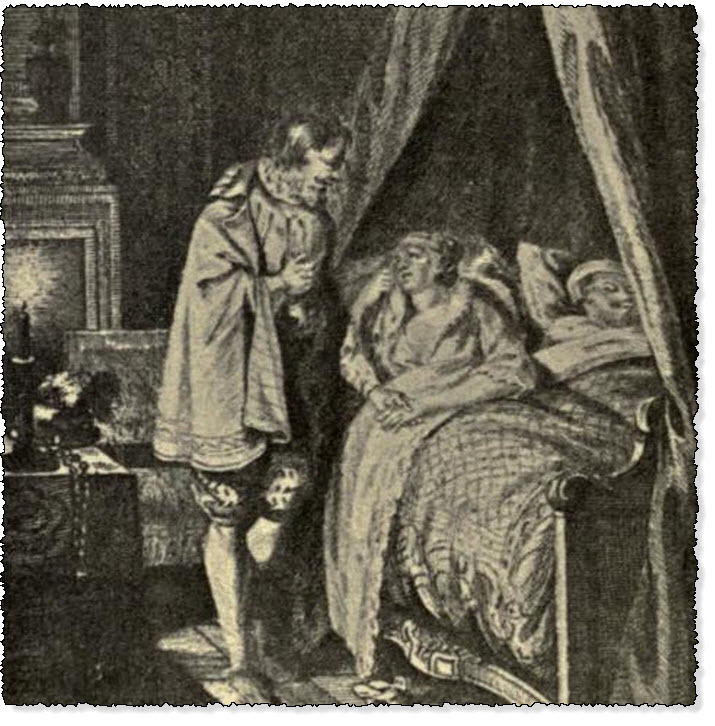

The Sea-captain Talking to The Lady

Day 2 of the Heptameron - Tale 13

Summary of the Third Tale Told on the Second Day of the Heptameron

Tale 13 of the Heptameron

In the household of the Lady-Regent, mother of King Francis, there was a very pious lady married to a gentleman of like mind with herself, and, albeit her husband was old and she was young and pretty, she served and loved him as though he had been the handsomest and youngest man in the world. So that she might give him no cause for sorrow, she set herself to live as though she were of the same age as himself, eschewing all such company, dress, dances, and amusements as young women are wont to love, and finding all her pleasure and recreation in the service of God; on which account her husband so loved and trusted her, that she ruled him and his household as she would.

One day it happened that the gentleman told his wife that from his youth up he had desired to make a journey to Jerusalem, and asked her what she thought of it. She, whose only wish was to please him, replied—

"Since God has withheld children from us, sweetheart, and has granted us sufficient wealth, I would willingly use some portion of it in making this sacred journey with you, for indeed, whether you go thither or elsewhere, I am resolved never to leave you."

At this the good man was so pleased, that it seemed to him as though he were already on Mount Calvary.

While they were deliberating on this matter, there came to the Court a gentleman, the Captain of a galley, who had often served in the wars against the Turks, (2) and was now soliciting the King of France to undertake an expedition against one of their cities, which might yield great advantage to Christendom. The old gentleman inquired of him concerning this expedition, and after hearing what he intended to do, asked him whether, on the completion of this business, he would make another journey to Jerusalem, whither he himself and his wife had a great desire to go. The Captain was well pleased on hearing of this laudable desire, and he promised to conduct them thither, and to keep the matter secret.

The old gentleman was all impatience to find his wife and tell her of what he had done. She was as anxious to make the journey as her husband, and on that account often spoke about it to the Captain, who, paying more attention to her person than her words, fell so deeply in love with her, that when speaking to her of the voyages he had made, he often confused the port of Marseilles with the Archipelago, and said "horse" when he meant to say "ship," like one distracted and bereft of sense. Her character, however, was such that he durst not give any token of the truth, and concealment kindled such fires in his heart that he often fell sick, when the lady showed as much solicitude for him as for the cross and guide of her road, (3) sending to inquire after him so often that the anxiety she showed cured him without the aid of any other medicine.

Several persons who knew that this Captain had been more renowned for valour and jollity than for piety, were amazed that he should have become so intimate with this lady, and seeing that he had changed in every respect, and frequented churches, sermons, and confessions, they suspected that this was only in order to win the lady's favour, and could not refrain from hinting as much to him.

The Captain feared that if the lady should hear any such talk he would be banished from her presence, and accordingly he told her husband and herself that he was on the point of being despatched on his journey by the King, and had much to tell them, but that for the sake of greater secrecy he did not desire to speak to them in the presence of others, for which reason he begged them to send for him when they had both retired for the night. The gentleman deemed this to be good advice, and did not fail to go to bed early every evening, and to make his wife also undress. When all their servants had left them, they used to send for the Captain, and talk with him about the journey to Jerusalem, in the midst of which the old gentleman would oft-times fall asleep with his mind full of pious thoughts. When the Captain saw the old gentleman asleep in bed, and found himself on a chair near her whom he deemed the fairest and noblest woman in the world, his heart was so rent between his desires and his dread of speaking that he often lost the power of speech. In order that she might not perceive this, he would force himself to talk of the holy places of Jerusalem where there were such signs of the great love that Jesus Christ bore us; and he would speak of this love, using it as a cloak for his own, and looking at the lady with sighs and tears which she never understood. By reason of his devout countenance she indeed believed him to be a very holy man, and begged of him to tell her what his life had been, and how he had come to love God in that way.

He told her that he was a poor gentleman, who, to arrive at riches and honour, had disregarded his conscience in marrying a woman who was too close akin to him, and this on account of the wealth she possessed, albeit she was ugly and old, and he loved her not; and when he had drawn all her money from her, he had gone to seek his fortune at sea, and had so prospered by his toil, that he had now come to an honourable estate. But since he had made his hearer's acquaintance, she, by reason of her pious converse and good example, had changed all his manner of life, and should he return from his present enterprise he was wholly resolved to take her husband and herself to Jerusalem, that he might thereby partly atone for his grievous sins which he had now put from him; save that he had not yet made reparation to his wife, with whom, however, he hoped that he might soon be reconciled.

The lady was well pleased with this discourse, and especially rejoiced at having drawn such a man to the love and fear of God. And thus, until the Captain departed from the Court, their long conversations together were continued every evening without his ever venturing to declare himself. However, he made the lady a present of a crucifix of Our Lady of Pity, (4) beseeching her to think of him whenever she looked upon it.

The hour of his departure arrived, and when he had taken leave of the husband, who was falling asleep, and came to bid his lady farewell, he beheld tears standing in her eyes by reason of the honourable affection which she entertained for him. The sight of these rendered his passion for her so unendurable that, not daring to say anything concerning it, he almost fainted, and broke out into an exceeding sweat, so that he seemed to weep not only with his eyes, but with his entire body. And thus he departed without speaking, leaving the lady in great astonishment, for she had never before seen such tokens of regret. Nevertheless she did not change in her good opinion of him, and followed him with her prayers.

After a month had gone by, however, as the lady was returning to her house, she met a gentleman who handed her a letter from the Captain, and begged her to read it in private.

He told her how he had seen the Captain embark, fully resolved to accomplish whatever might be pleasing to the King and of advantage to Christianity. For his own part, the gentleman added, he was straightway going back to Marseilles to set the Captain's affairs in order.

The lady withdrew to a window by herself, and opening the letter, found it to consist of two sheets of paper, covered on either side with writing which formed the following epistle:—

"Concealment long and silence have, alas! Brought me all comfortless to such a pass, That now, perforce, I must, to ease my grief, Either speak out, or seek in death relief. Wherefore the tale I long have left untold I now, in lonely friendlessness grown bold, Send unto thee, for I must strive to say My love, or else prepare myself to slay. And though my eyes no longer may behold The sweet, who in her hand my life doth hold, Whose glance sufficed to make my heart rejoice, The while my ear did listen to her voice,— These words at least shall meet her beauteous eyes, And tell her all the plaintive, clamorous cries Pent in my heart, to which I must give breath, Since longer silence could but bring me death. And yet, at first, I was in truth full fain To blot the words I'd written out again, Fearing, forsooth, I might offend thine ear With foolish phrases which, when thou wast near, I dared not utter; and 'Indeed,' said I, 'Far better pine in silence, aye, and die, Than save myself by bringing her annoy For whose sweet sake grim death itself were joy.' And yet, thought I, my death some pain might give To her for whom I would be strong, and live: For have I not, fair lady, promised plain, My journey ended, to return again And guide thee and thy spouse to where he now Doth yearn to call on God from Sion's brow? And none would lead thee thither should I die. If I were dead, methinks I see thee sigh In sore distress, for then thou couldst not start Upon that journey, dear unto thy heart. So I will live, and, in a little space, Return to lead thee to the sacred place. Aye, I will live, though death a boon would be Only to be refused for sake of thee. But if I live, I needs must straight remove The burden from my heart, and speak my love, That love more loyal, tender, deep, and true, Than, ever yet, the fondest lover knew. And now, bold words about to wing your flight, What will ye say when ye have reached her sight? Declare her all the love that fills my heart? Too weak ye are to tell its thousandth part! Can ye at least not say that her clear eyes Have torn my hapless heart forth in such wise, That like a hollow tree I pine and wither Unless hers give me back some life and vigour? Ye feeble words! ye cannot even tell How easily her eyes a heart compel; Nor can ye praise her speech in language fit, So weak and dull ye are, so void of wit. Yet there are some things I would have you name— How mute and foolish I oft time became When all her grace and virtue I beheld; How from my 'raptured eyes tears slowly welled The tears of hopeless love; how my tongue strayed From fond and wooing speech, so sore afraid, That all my discourse was of time and tide, And of the stars which up in Heav'n abide. O words, alas! ye lack the skill to tell The dire confusion that upon me fell, Whilst love thus wracked me; nor can ye disclose My love's immensity, its pains and woes. Yet, though, for all, your powers be too weak, Perchance, some little, ye are fit to speak— Say to her thus: "Twas fear lest thou shouldst chide That drove me, e'en so long, my love to hide, And yet, forsooth, it might have openly Been told to God in Heaven, as unto thee, Based as it is upon thy virtue—thought That to my torments frequent balm hath brought, For who, indeed, could ever deem it sin To seek the owner of all worth to win? Deserving rather of our blame were he Who having seen thee undisturbed could be.' None such was I, for, straightway stricken sore, My heart bowed low to Love, the conqueror. And ah! no false and fleeting love is mine, Such as for painted beauty feigns to pine; Nor doth my passion, although deep and strong, Seek its own wicked pleasure in thy wrong. Nay; on this journey I would rather die Than know that thou hadst fallen, and that I Had wrought thy shame and foully brought to harm The virtue which thy heart wraps round thy form. 'Tis thy perfection that I love in thee, Nought that might lessen it could ever be Desire of mine—indeed, the nobler thou, The greater were the love I to thee vow. I do not seek an ardent flame to quench In lustful dalliance with some merry wench, Pure is my heart, 'neath reason's calm control Set on a lady of such lofty soul, That neither God above nor angel bright, But seeing her, would echo my delight. And if of thee I may not be beloved, What matter, shouldst thou deem that I have proved The truest lover that did ever live? And this I know thou wilt, one day, believe, For time, in rolling by, shall show to thee No change in my heart's faith and loyalty. And though for this thou mayst make no return, Yet pleased am I with love for thee to burn, And seek no recompense, pursue no end, Save, that to thee, I meekly recommend My soul and body, which I here consign In sacrifice to Love's consuming shrine. If then in safety I sail back the main To thee, still artless, I'll return again; And if I die, then there will die with me A lover such as none again shall see. So Ocean now doth carry far away The truest lover seen for many a day; His body 'tis that journeys o'er the wave, But not his heart, for that is now thy slave, And from thy side can never wrested be, Nor of its own accord return to me. Ah! could I with me o'er the treach'rous brine Take aught of that pure, guileless heart of thine, No doubt should I then feel of victory, Whereof the glory would belong to thee. But now, whatever fortune may befall, I've cast the die; and having told thee all, Abide thereby, and vow my constancy— Emblem of which, herein, a diamond see, By whose great firmness and whose pure glow The strength and pureness of my love thou'lt know. Let it, I pray, thy fair white finger press, And thou wilt deal me more than happiness. And, diamond, speak and say: 'To thee I come From thy fond lover, who afar doth roam, And strives by dint of glorious deeds to rise To the high level of the good and wise, Hoping some day that haven to attain, Where thy sweet favours shall reward his pain."

The lady read the letter through, and was the more astonished at the Captain's passion as she had never before suspected it. She looked at the cutting of the diamond, which was a large and beautiful one, set in a ring of black enamel, and she was in great doubt as to what she ought to do with it. After pondering upon the matter throughout the night, she was glad to find that since there was no messenger, she had no occasion to send any answer to the Captain, who, she reflected, was being sufficiently tried by those matters of the King, his master, which he had in hand, without being angered by the unfavourable reply which she was resolved to make to him, though she delayed it until his return. However, she found herself greatly perplexed with regard to the diamond, for she had never been wont to adorn herself at the expense of any but her husband. For this reason, being a woman of excellent understanding, she determined to draw from the ring some profit to the Captain's conscience. She therefore despatched one of her servants to the Captain's wife with the following letter, which was written as though it came from a nun of Tarascon:—

"MADAM,—Your husband passed this way but a short time before he embarked, and after he had confessed himself and received his Creator like a good Christian, he spoke to me of something which he had upon his conscience, namely, his sorrow at not having loved you as he should have done. And on departing, he prayed and besought me to send you this letter, with the diamond which goes with it, and which he begs of you to keep for his sake, assuring you that if God bring him back again in health and strength, you shall be better treated than ever woman was before. And this stone of steadfastness shall be the pledge thereof.

"I beg you to remember him in your prayers; in mine he will have a place as long as I live."

This letter, being finished and signed with the name of a nun, was sent by the lady to the Captain's wife. And as may be readily believed, when the excellent old woman saw the letter and the ring, she wept for joy and sorrow at being loved and esteemed by her good husband when she could no longer see him. She kissed the ring a thousand times and more, watering it with her tears, and blessing God for having restored her husband's affection to her at the end of her days, when she had long looked upon it as lost. Nor did she fail to thank the nun who had given her so much happiness, but sent her the fairest reply that she could devise. This the messenger brought back with all speed to his mistress, who could not read it, nor listen to what her servant told her, without much laughter. And so pleased was she at having got rid of the diamond in so profitable a fashion as to bring about a reconciliation between the husband and wife, that she was as happy as though she had gained a kingdom.

A short time afterwards tidings came of the defeat and death of the poor Captain, and of how he had been abandoned by those who ought to have succoured him, and how his enterprise had been revealed by the Rhodians who should have kept it secret, so that he and all who landed with him, to the number of eighty, had been slain, among them being a gentleman named John, and a Turk to whom the lady of my story had stood godmother, both of them having been given by her to the Captain that he might take them with him on his journey. The first named of these had died beside the Captain, whilst the Turk, wounded by arrows in fifteen places, had saved himself by swimming to the French ships.

It was through him alone that the truth of the whole affair became known. A certain gentleman whom the poor Captain had taken to be his friend and comrade, and whose interests he had advanced with the King and the highest nobles of France, had, it appeared, stood out to sea with his ships as soon as the Captain landed; and the Captain, finding that his expedition had been betrayed, and that four thousand Turks were at hand, had thereupon endeavoured to retreat, as was his duty. But the gentleman in whom he put such great trust perceived that his friend's death would leave the sole command and profit of that great armament to himself, and accordingly pointed out to the officers that it would not be right to risk the King's vessels or the lives of the many brave men on board them in order to save less than a hundred persons, an opinion which was shared by all those of the officers that possessed but little courage.

So the Captain, finding that the more he called to the ships the farther they drew away from his assistance, faced round at last upon the Turks; and, albeit he was up to his knees in sand, he did such deeds of arms and valour that it seemed as though he alone would defeat all his enemies, an issue which his traitorous comrade feared far more than he desired it.

But at last, in spite of all that he could do, the Captain received so many wounds from the arrows of those who durst not approach within bowshot, that he began to lose all his blood, whereupon the Turks, perceiving the weakness of these true Christians, charged upon them furiously with their scimitars; but the Christians, so long as God gave them strength and life, defended themselves to the bitter end.

Then the Captain called to the gentleman named John, whom his lady love had given him, and to the Turk as well, and thrusting the point of his sword into the ground, fell upon his knees beside it, and embraced and kissed the cross, (5) saying—

"Lord, receive into Thy hands the soul of one who has not spared his life to exalt Thy name."

The gentleman called John, seeing that his master's life was ebbing away as he uttered these words, thought to aid him, and took him into his arms, together with the sword which he was holding. But a Turk who was behind them cut through both his thighs, whereupon he cried out, "Come, Captain, let us away to Paradise to see Him for whose sake we die," and in this wise he shared the poor Captain's death even as he had shared his life.

The Turk, seeing that he could be of no service to either of them, and being himself wounded by arrows in fifteen places, made off towards the ships, and requested to be taken on board. But although of all the eighty he was the only one who had escaped, the Captain's traitorous comrade refused his prayer. Nevertheless, being an exceeding good swimmer, he threw himself into the sea, and exerted himself so well that he was at last received on board a small vessel, where in a short time he was cured of his wounds. And it was by means of this poor foreigner that the truth became fully known, to the honour of the Captain and the shame of his comrade, whom the King and all the honourable people who heard the tidings deemed guilty of such wickedness toward God and man that there was no death howsoever cruel which he did not deserve. But when he returned he told so many lies, and gave so many gifts, that not only did he escape punishment, but even received the office of the man whose unworthy servant he had been.

When the pitiful tidings reached the Court, the Lady-Regent, who held the Captain in high esteem, mourned for him exceedingly, as did the King and all the honourable people who had known him. And when the lady whom he had loved the best heard of his strange, sad, and Christian death, she changed the chiding she had resolved to give him into tears and lamentations, in which her husband kept her company, all hopes of their journey to Jerusalem being now frustrated.

I must not forget to say that on the very day when the two gentlemen were killed, a damsel in the lady's service, who loved the gentleman called John better than herself, came and told her mistress that she had seen her lover ir a dream; he had appeared to her clad in white, and had bidden her farewell, telling her that he was going to Paradise with his Captain. And when the damsel heard that her dream had come true, she made such lamentation that her mistress had enough to do to comfort her. (6)

A short time afterwards the Court journeyed into Normandy, to which province the Captain had belonged. His wife was not remiss in coming to pay homage to the Lady-Regent, and in order that she might be presented to her, she had recourse to the same lady whom her husband had so dearly loved.

And while they were waiting in a church for the appointed hour, she began bewailing and praising her husband, saying among other things to the lady—

"Alas, madam! my misfortune is the greatest that ever befell a woman, for just when he was loving me more than he had ever done, God took him from me."

Heptameron Story 13

So saying, and with many tears, she showed the ring which she wore on her finger as a token of her husband's perfect love, whereat the other lady, finding that her deception had resulted in such a happy issue, was, despite her sorrow for the Captain's death, so moved to laughter, that she would not present the widow to the Regent, but committed her to the charge of another lady, and withdrew into a side chapel, where she satisfied her inclination to laugh.

"I think, ladies, that those who receive such gifts ought to seek to use them to as good a purpose as did this worthy lady. They would find that benefactions bring joy to those who bestow them. And we must not charge this lady with deceit, but esteem her good sense which turned to good that which in itself was worthless."

"Do you mean to say," said Nomerfide, "that a fine diamond, costing two hundred crowns, is worthless? I can assure you that if it had fallen into my hands, neither his wife nor his relations would have seen aught of it. Nothing is more wholly one's own than a gift. The gentleman was dead, no one knew anything about the matter, and she might well have spared the poor old woman so much sorrow."

"By my word," said Hircan, "you are right. There are women who, to make themselves appear of better heart than others, do things that are clearly contrary to their notions, for we all know that women are the most avaricious of beings, yet their vanity often surpasses their avarice, and constrains their hearts to actions that they would rather not perform. My belief is that the lady who gave the diamond away in this fashion was unworthy to wear it."

"Softly, softly," said Oisille; "I believe I know who she is, and I therefore beg that you will not condemn her unheard."

"Madam," said Hircan, "I do not condemn her at all; but if the gentleman was as virtuous as you say, it were an honour to have such a lover, and to wear his ring; but perhaps some one less worthy of being loved than he held her so fast by the finger that the ring could not be put on."

"Truly," said Ennasuite, "she might well have kept it, seeing that no one knew anything about it."

"What!" said Geburon; "are all things lawful to those who love, provided no one knows anything about them?"

"By my word," said Saffredent, "the only misdeed that I have ever seen punished is foolishness. There is never a murderer, robber, or adulterer condemned by the courts or blamed by his fellows, if only he be as cunning as he is wicked. Oft-time, however, a bad man's wickedness so blinds him that he becomes a fool; and thus, as I have just said, it is the foolish only that are punished, not the vicious."

"You may say what you please," said Oisille, "only God can judge the lady's heart; but for my part, I think that her action was a very honourable and virtuous one. (7) However, to put an end to the debate, I pray you, Parlamente, to give some one your vote."

"I give it willingly," she said, "to Simontault, for after two such mournful tales we must have one that will not make us weep."

"I thank you," said Simontault. "In giving me your vote you have all but told me that I am a jester. It is a name that is extremely distasteful to me, and in revenge I will show you that there are women who with certain persons, or for a certain time, make a great pretence of being chaste, but the end shows them in their real colours, as you will see by this true story."

Footnotes:

- M. Le Roux de Lincy believes that this story has some historical basis, and, Louise of Savoy being termed the Regent, he assigns the earlier incidents to the year 1524. But Louise was Regent, for the first time, in 1515, and we incline to the belief that Queen Margaret alludes to this earlier period. Note the reference to a Court journey to Normandy (post, p. 136), which was probably the journey that Francis I. and his mother are known to have made to Rouen and Alenšon in the autumn of 1517. See vol. i. p. xxviii.— Ed. 2 119

- M. Paul Lacroix, who believes that the heroine of this tale is Margaret herself (she is described as telling it under the name of Parlamente), is also of opinion that the gentleman referred to is the Baron de Malleville, a knight of Malta, who was killed at Beyrout during an expedition against the Turks, and whose death was recounted in verse by Clement Marot (OEuvres, 1731, vol. ii. p. 452-455). Margaret's gentleman, however, is represented as being married, whereas M. de Malleville, as a knight of Malta, was necessarily a bachelor. Marot, moreover, calls Malleville a Parisian, whereas the gentleman in the tale belonged to Normandy (see post, p. 136).—B. J. and L.

- This may simply be an allusion to wayside crosses which serve to guide travellers on their road. M. de Montaiglon points out, however, that in the alphabets used for teaching children in the olden time, the letter A was always preceded by a cross, and that the child, in reciting, invariably began: "The cross of God, A, B, C, D," &c. In a like way, a cross figured at the beginning of the guide-books of the time, as a symbol inviting the traveller to pray, and reminding him upon whom he should rely amid the perils of his journey. The best known French guide-book of the sixteenth century is Charles Estienne's Guide des Chemins de France.—M. and Ed.

- "Our Lady of Pity" is the designation usually applied to the Virgin when she is shown seated with the corpse of Christ on her knees. Michael Angelo's famous group at St. Peter's is commonly known by this name. In the present instance, however, Queen Margaret undoubtedly refers to a crucifix showing the Virgin at the foot of the Cross, contemplating her son's sufferings. Such crucifixes were formerly not uncommon.—M.

- As is well known, before swords were made with shell and stool hilts, the two guards combined with the handle and blade formed a cross. Bayard, when dying, raised his sword to gaze upon this cross, and numerous instances, similar to that mentioned above by Queen Margaret, may be found in the old Chansons de Geste.—M.

- The Queen of Navarre was a firm believer in the truth and premonitory character of dreams, and according to her biographers she, herself, had several singular ones, two of which are referred to in the Memoir prefixed to the present work (vol. i. pp. lxxxiii. and Ixxxvii.). In some of her letters, moreover, she relates that Francis I., when under the walls of Pavia, on three successive nights beheld his little daughter Charlotte (then dying at Lyons) appear to him in a dream, and on each occasion repeat the words, "Farewell, my King, I am going to Paradise."—Ed.

- In our opinion this sentence disposes of Miss Mary Robinson's supposition (The Fortunate Lovers, London, 1887, p. 159) that Oisille (i.e., Louise of Savoy) is the real heroine of this tale. Queen Margaret would hardly have represented her commending her own action. If any one of the narrators of the Heptameron be the heroine of the story, the presumptions are in favour of Longarine (La Dame de Lonray), Margaret's bosom friend, whose silence during the after-converse is significant.—Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.