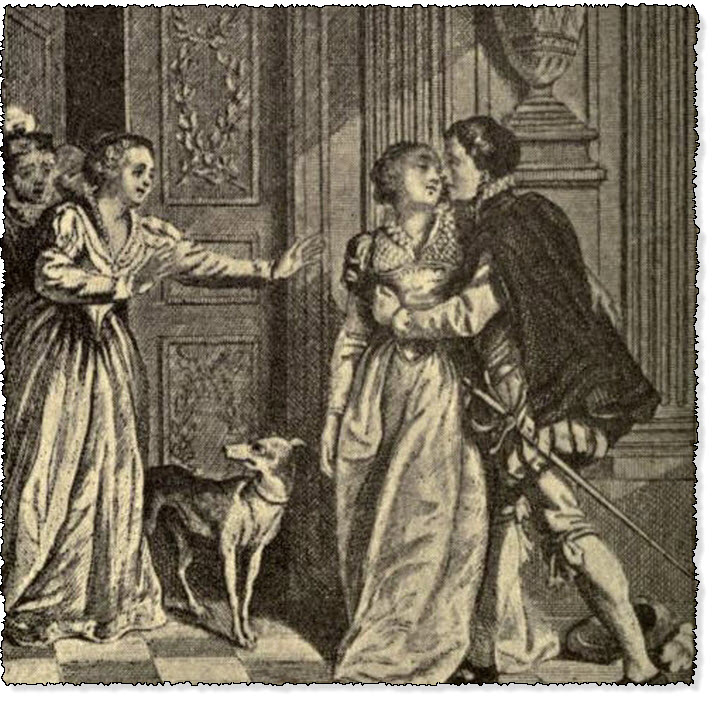

the Parting Between Pauline and The Gentlemen

Day 2 of the Heptameron - Tale 19

Summary of the Ninth Tale Told on the Second Day of the Heptameron

Tale 19 of the Heptameron

Story 19

In the time of the Marquis of Mantua, (2) who had married the sister of the Duke of Ferrara, there lived in the household of the Duchess a damsel named Pauline, who was greatly loved by a gentleman in the Marquis's service, and this to the astonishment of every one; for being poor, albeit handsome and greatly beloved by his master, he ought, in their estimation, to have wooed some wealthy dame, but he believed that all the world's treasure centred in Pauline, and looked to his marriage with her to gain and possess it.

The Marchioness, who desired that Pauline should through her favour make a more wealthy marriage, discouraged her as much as she could from wedding the gentleman, and often hindered the two lovers from talking together, pointing out to them that, should the marriage take place, they would be the poorest and sorriest couple in all Italy. But such argument as this was by no means convincing to the gentleman, and though Pauline, on her side, dissembled her love as well as she could, she none the less thought about him as often as before.

With the hope that time would bring them better fortune, this love of theirs continued for a long while, during which it chanced that a war broke out (3) and that the gentleman was taken prisoner along with a Frenchman, whose heart was bestowed in France even as was his own in Italy.

Finding themselves comrades in misfortune, they began to tell their secrets to one another, the Frenchman confessing that his heart was a fast prisoner, though he gave not the name of its prison-house. However, as they were both in the service of the Marquis of Mantua, this French gentleman knew right well that his companion loved Pauline, and in all friendship for him advised him to lay his fancy aside. This the Italian gentleman swore was not in his power, and he declared that if the Marquis of Mantua did not requite him for his captivity and his faithful service by giving him his sweetheart to wife, he would presently turn friar and serve no master but God. This, however, his companion could not believe, perceiving in him no token of devotion, unless it were that which he bore to Pauline.

At the end of nine months the French gentleman obtained his freedom, and by his diligence compassed that of his comrade also, who thereupon used all his efforts with the Marquis and Marchioness to bring about his marriage with Pauline. But all was of no avail; they pointed out to him the poverty wherein they would both be forced to live, as well as the unwillingness of the relatives on either side; and they forbade him ever again to speak with the maiden, to the end that absence and lack of opportunity might quell his passion.

Finding himself compelled to obey, the gentleman begged of the Marchioness that he might have leave to bid Pauline farewell, promising that he would afterwards speak to her no more, and upon his request being granted, as soon as they were together he spoke to her as follows:—

"Heaven and earth are both against us, Pauline, and hinder us not only from marriage but even from having sight and speech of one another. And by laying on us this cruel command, our master and mistress may well boast of having with one word broken two hearts, whose bodies, perforce, must henceforth languish; and by this they show that they have never known love or pity, and although I know that they desire to marry each of us honourably and to worldly advantage,—ignorant as they are that contentment is the only true wealth,—yet have they so afflicted and angered me that never more can I do them loyal service. I feel sure that had I never spoken of marriage they would not have shown themselves so scrupulous as to forbid me from speaking to you; but I would have you know that, having loved you with a pure and honourable love, and wooed you for what I would fain defend against all others, I would rather die than change my purpose now to your dishonour. And since, if I continued to see you, I could not accomplish so harsh a penance as to restrain myself from speech, whilst, if being here I saw you not, my heart, unable to remain void, would fill with such despair as must end in woe, I have resolved, and that long since, to become a monk. I know, indeed, full well that men of all conditions may be saved, but would gladly have more leisure for contemplating the Divine goodness, which will, I trust, forgive me the errors of my youth, and so change my heart that it may love spiritual things as truly as hitherto it has loved temporal things. And if God grant me grace to win His grace, my sole care shall be to pray to Him without ceasing for you; and I entreat you, by the true and loyal love that has been betwixt us both, that you will remember me in your prayers, and beseech Our Lord to grant me as full a measure of steadfastness when I see you no more, as he has given me of joy in beholding you. Finally, I have all my life hoped to have of you in wedlock that which honour and conscience allow, and with this hope have been content; but now that I have lost it and can never have you to wife, I pray you at least, in bidding me farewell, treat me as a brother, and suffer me to kiss you."

When the hapless Pauline, who had always treated him somewhat rigorously, beheld the extremity of his grief and his uprightness, which, amidst all his despair, would suffer him to prefer but this moderate request, her sole answer was to throw her arms around his neck, weeping so bitterly that speech and strength alike failed her, and she swooned away in his embrace. Thereupon, overcome by pity, love and sorrow, he must needs swoon also, and one of Pauline's companions, seeing them fall one on one side and one on the other, called aloud for aid, whereupon remedies were fetched and applied, and brought them to themselves.

Then Pauline, who had desired to conceal her love, was ashamed at having shown such transports; yet were her pity for the unhappy gentleman a just excuse. He, unable to utter the "Farewell for ever!" hastened away with heavy heart and set teeth, and, on entering his apartment, fell like a lifeless corpse upon his bed. There he passed the night in such piteous lamentations that his servants thought he must have lost all his relations and friends, and whatsoever he possessed on earth.

In the morning he commended himself to Our Lord, and having divided among his servants what little worldly goods he had, save a small sum of money which he took, he charged his people not to follow him, and departed all alone to the monastery of the Observance, (4) resolved to take the cloth there and never more to quit it his whole life long.

Heptameron Story 19

The Warden, who had known him in former days, at first thought he was being laughed at or was dreaming, for there was none in all the land that less resembled a Grey Friar than did this gentleman, seeing that he was endowed with all the good and honourable qualities that one would desire a gentleman to possess. Albeit, after hearing his words and beholding the tears that flowed (from what cause he knew not) down his face, the Warden compassionately took him in, and very soon afterwards, finding him persevere in his desire, granted him the cloth: whereof tidings were brought to the Marquis and Marchioness, who thought it all so strange that they could scarcely believe it.

Pauline, wishing to show herself untrammelled by any passion, strove as best she might to conceal her sorrow, in such wise that all said she had right soon forgotten the deep affection of her faithful lover. And so five or six months passed by without any sign on her part, but in the meanwhile some monk had shown her a song which her lover had made a short time after he had taken the cowl. The air was an Italian one and pretty well known; as for the words, I have put them into our own tongue as nearly as I can, and they are these:—

What word shall be Hers unto me, When I appear in convent guise Before her eyes? Ah! sweet maiden, Lone, heart-laden, Dumb because of days that were; When the streaming Tears are gleaming 'Mid the streaming of thy hair, Ah! with hopes of earth denied thee, Holiest thoughts will heavenward guide thee To the hallowing cloister's door. What word shall be, &c. What shall they say, Who wronged us, they Who have slain our heart's desire, Seeing true love Doth flawless prove, Thus tried as gold in fire? When they see my heart is single, Their remorseful tears shall mingle, Each and other weeping sore. What word shall be, &c. And should they come To will us home, How vain were all endeavour! "Nay, side by side, "We here shall bide "Till soul from soul shall sever. "Though of love your hate bereaves us "Yet the veil and cowl it leaves us, "We shall wear till life be o'er." What word shall be, &c. And should they move Our flesh to love Once more the mockers, singing Of fruits and flowers In golden hours For mated hearts upspringing; We shall say: "Our lives are given, Flower and fruit, to God in Heaven, Who shall hold them evermore." What word shall be, &c. O victor Love! Whose might doth move My wearied footsteps hither, Here grant me days Of prayer and praise, Grant faith that ne'er shall wither; Love of each to either given, Hallowed by the grace of Heaven, God shall bless for evermore. What word shall be, &c. Avaunt Earth's weal! Its bands are steel To souls that yearn for Heaven; Avaunt Earth's pride! Deep Hell shall hide Hearts that for fame have striven. Far be lust of earthly pleasure, Purity, our priceless treasure, Christ shall grant us of His store. What word shall be, &c. Swift be thy feet, My own, my sweet, Thine own true lover follow; Fear not the veil, The cloister's pall Keeps far Earth's spectres hollow. Sinks the fire with fitful flashes, Soars the Phoenix from his ashes, Love yields Life for evermore. What word shall be, &c. Love, that no power Of dreariest hour, Could change, no scorn, no rage, Now heavenly free From Earth shall be, In this, our hermitage. Winged of love that upward, onward, Ageless, boundless, bears us sunward, To the heavens our souls shall soar. What word shall be, &c.

On reading these verses through in a chapel where she was alone, Pauline began to weep so bitterly that all the paper was wetted with her tears. Had it not been for her fear of showing a deeper affection than was seemly, she would certainly have withdrawn forthwith to some hermitage, and never have looked upon a living being again; but her native discretion moved her to dissemble for a little while longer. And although she was now resolved to leave the world entirely, she feigned the very opposite, and so altered her countenance, that in company she was altogether unlike her real self. For five or six months did she carry this secret purpose in her heart, making a greater show of mirth than had ever been her wont.

But one day she went with her mistress to the Observance to hear high mass, and when the priest, the deacon and the sub-deacon came out of the vestry to go to the high altar, she saw her hapless lover, who had not yet fulfilled his year of novitiate, acting as acolyte, carrying the two vessels covered with a silken cloth, and walking first with his eyes upon the ground. When Pauline saw him in such raiment as did rather increase than diminish his comeliness, she was so exceedingly moved and disquieted, that to hide the real reason of the colour that came into her face, she began to cough. Thereupon her unhappy lover, who knew this sound better than that of the cloister bells, durst not turn his head; still on passing in front of her he could not prevent his eyes from going the road they had so often gone before; and whilst he thus piteously gazed on Pauline, he was seized in such wise by the fire which he had considered well-nigh quelled, that whilst striving to conceal it more than was in his power, he fell at full length before her. However, for fear lest the cause of his fall should be known, he was led to say that it was by reason of the pavement of the church being broken in that place.

When Pauline perceived that the change in his dress had not wrought any change in his heart, and that so long a time had gone by since he had become a monk, that every one believed her to have forgotten him, she resolved to fulfil the desire she had conceived to bring their love to a like ending in respect of raiment, condition and mode of life, even as these had been akin at the time when they abode together in the same house, under the same master and mistress. More than four months previously she had carried out all needful measures for taking the veil, and now, one morning she asked leave of the Marchioness to go and hear mass at the convent of Saint Clara, (5) which her mistress granted her, not knowing the reason of her request. But in passing by the monastery of the Grey Friars, she begged the Warden to summon her lover, saying that he was her kinsman, and when they met in a chapel by themselves, she said to him:—

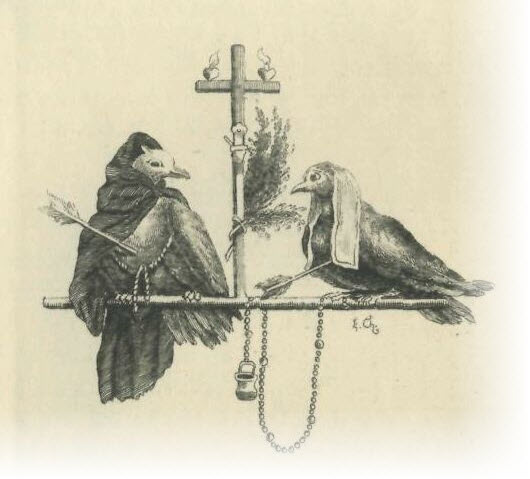

"Had my honour suffered me to seek the cloister as soon as you, I should not have waited until now; but having at last by my patience baffled the slander of those who are more ready to think evil than good, I am resolved to take the same condition, raiment and life as you have taken. Nor do I inquire of what manner they are; if you fare well, I shall partake of your welfare, and if you fare ill, I would not be exempt. By whatsoever path you are journeying to Paradise I too would follow; for I feel sure that He who alone is true and perfect, and worthy to be called Love, has drawn us to His service by means of a virtuous and reasonable affection, which He will by His Holy Spirit turn wholly to Himself. Let us both, I pray you, put from us the perishable body of the old Adam, and receive and put on the body of our true Spouse, who is the Lord Jesus Christ."

The monk-lover was so rejoiced to hear of this holy purpose, that he wept for gladness and did all that he could to strengthen her in her resolve, telling her that since the pleasure of hearing her words was the only one that he might now seek, he deemed himself happy to dwell in a place where he should always be able to hear them. He further declared that her condition would be such that they would both be the better for it; for they would live with one love, with one heart and with one mind, guided by the goodness of God, whom he prayed to keep them in His hand, wherein none can perish. So saying, and weeping for love and gladness, he kissed her hands; but she lowered her face upon them, and then, in all Christian love, they gave one another the kiss of hallowed affection.

And so, in this joyful mood Pauline left him, and came to the convent of Saint Clara, where she was received and took the veil, whereof she sent tidings to her mistress, the Marchioness, who was so amazed that she could not believe it, but came on the morrow to the convent to see Pauline and endeavour to turn her from her purpose. But Pauline replied that she, her mistress, had had the power to deprive her of a husband in the flesh, the man whom of all men she had loved the best, and with that she must rest content, and not seek to sever her from One who was immortal and invisible, for this Was neither in her power nor in that of any creature upon earth.

The Marchioness, finding her thus steadfast in her resolve, kissed her and left her, with great sorrow.

And thenceforward Pauline and her lover lived such holy and devout lives, observing all the rules of their order, that we cannot doubt that He whose law is love told them when their lives were ended, as He had told Mary Magdalene: "Your sins are forgiven, for ye have loved much;" and doubtless He removed them in peace to that place where the recompense surpasses all the merits of man.

"You cannot deny, ladies, that in this case the man's love was the greater of the two; nevertheless, it was so well requited that I would gladly have all lovers equally rewarded."

"Then," said Hircan, "there would be more manifest fools among men and women than ever there were."

"Do you call it folly," said Oisille, "to love virtuously in youth and then to turn this love wholly to God?"

"If melancholy and despair be praiseworthy," answered Hircan, laughing, "I will acknowledge that Pauline and her lover are well worthy of praise."

"True it is," said Geburon, "that God has many ways of drawing us to Himself, and though they seem evil in the beginning, yet in the end they are good."

"Moreover," said Parlamente, "I believe that no man can ever love God perfectly that has not perfectly loved one of His creatures in this world."

"What do you mean by loving perfectly?" asked Saffredent. "Do you consider that those frigid beings who worship their mistresses in silence and from afar are perfect lovers?"

"I call perfect lovers," replied Parlamente, "those who seek perfection of some kind in the objects of their love, whether beauty, or goodness, or grace, ever tending to virtue, and who have such noble and upright hearts that they would rather die than do base things, contrary and repugnant to honour and conscience. For the soul, which was created for nothing but to return to its sovereign good, is, whilst enclosed in the body, ever desirous of attaining to it. But since the senses, through which the soul receives knowledge, are become dim and carnal through the sin of our first parent, they can show us only those visible things that approach towards perfection; and these the soul pursues, thinking to find in outward beauty, in a visible grace and in the moral virtues, the supreme, absolute beauty, grace and virtue. But when it has sought and tried these external things and has failed to find among them that which it really loves, the soul passes on to others; wherein it is like a child, which, when very young, will be fond of dolls and other trifles, the prettiest its eyes can see, and will heap pebbles together in the idea that these form wealth; but as the child grows older he becomes fond of living dolls, and gathers together the riches that are needful for earthly life. And when he learns by greater experience that in all these earthly things there is neither perfection nor happiness, he is fain to seek Him who is the Creator and Author of happiness and perfection. Albeit, if God should not give him the eye of Faith, he will be in danger of passing from ignorance to infidel philosophy, since it is Faith alone that can teach and instil that which is right; for this, carnal and fleshly man can never comprehend." (6)

"Do you not see," said Longarine, "that uncultivated ground which bears plants and trees in abundance, however useless they may be, is valued by men, because it is hoped that it will produce good fruit if this be sown in it? In like manner, if the heart of man has no feeling of love for visible things, it will never arrive at the love of God by the sowing of His Word, for the soul of such a heart is barren, cold and worthless."

"That," said Saffredent, "is the reason why most of the doctors are not spiritual. They never love anything but good wine and dirty, ill-favoured serving-women, without making trial of the love of honourable ladies."

"If I could speak Latin well," said Simontault, "I would quote you St. John's words: 'He that loveth not his brother whom he hath seen, how can he love God whom he hath not seen?' (7) From visible things we are led on to love those that are invisible."

"If," said Ennasuite, "there be a man as perfect as you say, quis est ille et laudabimus eum?" (8)

"There are men," said Dagoucin, "whose love is so strong and true that they would rather die than harbour a wish contrary to the honour and conscience of their mistress, and who at the same time are unwilling that she or others should know what is in their hearts."

"Such men," said Saffredent, "must be of the nature of the chameleon, which lives on air. (9) There is not a man in the world but would fain declare his love and know that it is returned; and further, I believe that love's fever is never so great, but it quickly passes off when one knows the contrary. For myself, I have seen manifest miracles of this kind."

"I pray you then," said Ennasuite, "take my place and tell us about some one that was recalled from death to life by having discovered in his mistress the very opposite of his desire."

"I am," said Saffredent, "so much afraid of displeasing the ladies, whose faithful servant I have always been and shall always be, that without an express command from themselves I should never have dared to speak of their imperfections. However, in obedience to them, I will hide nothing of the truth."

Footnotes:

- The incidents related in this tale appear to have taken place at Mantua and Ferrara. M. de Montaiglon, however, believes that they happened at Lyons, and that Margaret laid the scene of her story in Italy, so that the personages she refers to might not be identified. The subject of the tale is similar to that of the poem called L'Amant rendu Cordelier ŕ l'Observance et Amour, which may perhaps have supplied the Queen of Navarre with the plot of her narrative.—M. and Ed.

- This was John Francis II. of Gonzaga, who was born in 1466, and succeeded his father, Frederic I., in 1484. He took an active part in the wars of the time, commanding the Venetian troops when Charles VIII. invaded Italy, and afterwards supporting Ludovico Sforza in the defence of Milan. When Sforza abandoned the struggle against France, the Marquis of Mantua joined the French king, for whom he acted as viceroy of Naples. Ultimately, however, he espoused the cause of the Emperor Maximilian, when the latter was at war with Venice in 1509, and being surprised and defeated while camping on the island of La Scala, he fled in his shirt and hid himself in a field, where, by the treachery of a peasant who had promised him secrecy, he was found and taken prisoner. By the advice of Pope Julius II., the Venetians set him at liberty after he had undergone a year's imprisonment. In 1490 John Francis married Isabella d'Esté, daughter of Hercules I. Duke of Ferrara, by whom he had several children. He died at Mantua in March 1519, his widow surviving him until 1539. Among the many dignities acquired by the Marquis in the course of his singularly chequered life was that of gonfalonier of the Holy Church, conferred upon him by Julius II.—L. and En.

- This would be the expedition which Louis XII. made into Italy in 1503 in view of conquering the Kingdom of Naples, and which was frustrated by the defeats that the French army sustained at Seminara, Cerignoles, and the passage of the Garigliano.—D.

- The monastery of the Observance here referred to would appear to be that at Ferrara, founded by Duke Hercules I., father of the Marchioness of Mantua. The name of "Observance" was given to those conventual establishments where the rules of monastic life were scrupulously observed, however rigorous they might be. The monastery of the Observance at Ferrara belonged to the Franciscan order, reformed by the Pope in 1363.—D. and L.

- There does not appear to have been a church of St. Clara at Mantua, but there was one attached to a convent of that name at Ferrara.—M. and D.

- The whole of this mystical dissertation appears to have been inspired by some remarks in Castiglione's Libro del Cortegiano (The Book of the Courtier) —which Margaret was no doubt well acquainted with, as it was translated into French in 1537 by Jacques Colin, her brother's secretary. This work, which indeed seems to have suggested several passages in the Heptameron, was at that time as widely read in France as in Italy and Spain.—B. J. and D.

- I St. John, iv. 20.

- We have been unable to find this anywhere in the Scriptures.—Ed.

- A popular fallacy. The chameleon undoubtedly feeds upon small insects.—D.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.