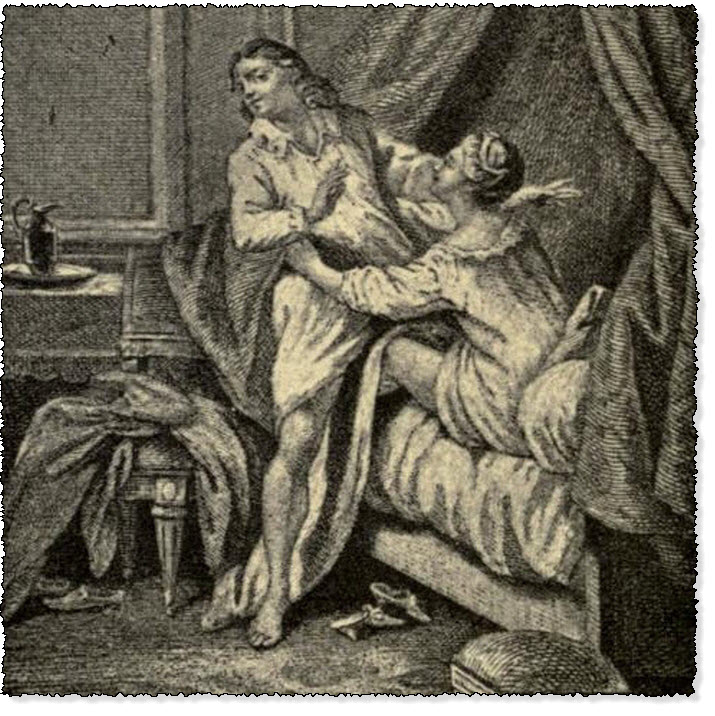

the Student Escaping The Temptation

Day 2 of the Heptameron - Tale 18

Summary of the Eighth Tale Told on the Second Day of the Heptameron

Tale 18 of the Heptameron

In one of the goodly towns of the kingdom of France there dwelt a nobleman of good birth, who attended the schools that he might learn how virtue and honour are to be acquired among virtuous men. But although he was so accomplished that at the age of seventeen or eighteen years he was, as it were, both precept and example to others, Love failed not to add his lesson to the rest; and, that he might be the better hearkened to and received, concealed himself in the face and the eyes of the fairest lady in the whole country round, who had come to the city in order to advance a suit-at-law. But before Love sought to vanquish the gentleman by means of this lady's beauty, he had first won her heart by letting her see the perfections of this young lord; for in good looks, grace, sense and excellence of speech he was surpassed by none.

You, who know what speedy way is made by the fire of love when once it fastens on the heart and fancy, will readily imagine that between two subjects so perfect as these it knew little pause until it had them at its will, and had so filled them with its clear light, that thought, wish and speech were all aflame with it. Youth, begetting fear in the young lord, led him to urge his suit with all the gentleness imaginable; but she, being conquered by love, had no need of force to win her. Nevertheless, shame, which tarries with ladies as long as it can, for some time restrained her from declaring her mind. But at last the heart's fortress, which is honour's abode, was shattered in such sort that the poor lady consented to that which she had never been minded to refuse.

In order, however, to make trial of her lover's patience, constancy and love, she only granted him what he sought on a very hard condition, assuring him that if he fulfilled it she would love him perfectly for ever; whereas, if he failed in it, he would certainly never win her as long as he lived. And the condition was this:—she would be willing to talk with him, both being in bed together, clad in their linen only, but he was to ask nothing more from her than words and kisses.

He, thinking there was no joy to be compared to that which she promised him, agreed to the proposal, and that evening the promise was kept; in such wise that, despite all the caresses she bestowed on him and the temptations that beset him, he would not break his oath. And albeit his torment seemed to him no less than that of Purgatory, yet was his love so great and his hope so strong, sure as he felt of the ceaseless continuance of the love he had thus painfully won, that he preserved his patience and rose from beside her without having done anything contrary to her expressed wish. (2)

The lady was, I think, more astonished than pleased by such virtue; and giving no heed to the honour, patience and faithfulness her lover had shown in the keeping of his oath, she forthwith suspected that his love was not so great as she had thought, or else that he had found her less pleasing than he had expected.

She therefore resolved, before keeping her promise, to make a further trial of the love he bore her; and to this end she begged him to talk to a girl in her service, who was younger than herself and very beautiful, bidding him make love speeches to her, so that those who saw him come so often to the house might think that it was for the sake of this damsel and not of herself.

The young lord, feeling sure that his own love was returned in equal measure, was wholly obedient to her commands, and for love of her compelled himself to make love to the girl; and she, finding him so handsome and well-spoken, believed his lies more than other truth, and loved him as much as though she herself were greatly loved by him.

The mistress finding that matters were thus well advanced, albeit the young lord did not cease to claim her promise, granted him permission to come and see her at one hour after midnight, saying that after having so fully tested the love and obedience he had shown towards her, it was but just that he should be rewarded for his long patience. Of the lover's joy on hearing this you need have no doubt, and he failed not to arrive at the appointed time.

But the lady, still wishing to try the strength of his love, had said to her beautiful damsel—

"I am well aware of the love a certain nobleman bears to you, and I think you are no less in love with him; and I feel so much pity for you both, that I have resolved to afford you time and place that you may converse together at your ease."

The damsel was so enchanted that she could not conceal her longings, but answered that she would not fail to be present.

In obedience, therefore, to her mistress's counsel and command, she undressed herself and lay down on a handsome bed, in a room the door of which the lady left half-open, whilst within she set a light so that the maiden's beauty might be clearly seen. Then she herself pretended to go away, but hid herself near to the bed so carefully that she could not be seen.

Her poor lover, thinking to find her according to her promise, failed not to enter the room as softly as he could, at the appointed hour; and after he had shut the door and put off his garments and fur shoes, he got into the bed, where he looked to find what he desired. But no sooner did he put out his arms to embrace her whom he believed to be his mistress, than the poor girl, believing him entirely her own, had her arms round his neck, speaking to him the while in such loving words and with so beautiful a countenance, that there is not a hermit so holy but he would have forgotten his beads for love of her.

But when the gentleman recognised her with both eye and ear, and found he was not with her for whose sake he had so greatly suffered, the love that had made him get so quickly into the bed, made him rise from it still more quickly. And in anger equally with mistress and damsel, he said—

"Neither your folly nor the malice of her who put you there can make me other than I am. But do you try to be an honest woman, for you shall never lose that good name through me."

Heptameron Story 18

So saying he rushed out of the room in the greatest wrath imaginable, and it was long before he returned to see his mistress. However love, which is never without hope, assured him that the greater and more manifest his constancy was proved to be by all these trials, the longer and more delightful would be his bliss.

The lady, who had seen and heard all that passed, was so delighted and amazed at beholding the depth and constancy of his love, that she was impatient to see him again in order to ask his forgiveness for the sorrow that she had caused him to endure. And as soon as she could meet with him, she failed not to address him in such excellent and pleasant words, that he not only forgot all his troubles but even deemed them very fortunate, seeing that their issue was to the glory of his constancy and the perfect assurance of his love, the fruit of which he enjoyed from that time forth as fully as he could desire, without either hindrance or vexation. (3)

"I pray you, ladies, find me if you can a woman who has ever shown herself as constant, patient and true as was this man. They who have experienced the like temptations deem those in the pictures of Saint Antony very small in comparison; for one who can remain chaste and patient in spite of beauty, love, opportunity and leisure, will have virtue enough to vanquish every devil."

"Tis a pity," said Oisille, "that he did not address his love to a woman possessing as much virtue as he possessed himself. Their amour would then have been the most perfect and honourable that was ever heard of."

"But prithee tell me," said Geburon, "which of the two trials do you deem the harder?"

"I think the last," said Parlamente, "for resentment is the strongest of all temptations."

Longarine said she thought that the first was the most arduous to sustain, since to keep his promise it was needful he should subdue both love and himself.

"It is all very well for you to talk," said Simontault, "it is for us who know the truth of the matter to say what we think of it. For my own part, I think he was stupid the first time and witless the second; for I make no doubt that, while he was keeping his promise, to his mistress, she was put to as much trouble as himself, if not more. She had him take the oath only in order to make herself out a more virtuous woman than she really was; she must have well known that strong love will not be bound by commandment or oath, or aught else on earth, and she simply sought to give a show of virtue to her vice, as though she could be won only through heroic virtues. And the second time he was witless to leave a woman who loved him, and who was worth more than his pledged mistress, especially when his displeasure at the trick played upon him had been a sound excuse."

Here Dagoucin put in that he was of the contrary opinion, and held that the gentleman had on the first occasion shown himself constant, patient and true, and on the second occasion loyal and perfect in his love.

"And how can we tell," asked Saffredent, "that he was not one of those that a certain chapter calls de frigidis et malificiatis?" (4)

"To complete his eulogy, Hircan ought to have told us how he comported himself when he obtained what he wanted, and then we should have been able to judge whether it was virtue or impotence that made him observe so much discretion."

"You may be sure," said Hircan, "that had he told me this I should have concealed it as little as I did the rest. Nevertheless, from seeing his person and knowing his temper, I shall ever hold that his conduct was due to the power of love rather than to any impotence or coldness."

"Well, if he was such as you say," said Simontault, "he ought to have broken his oath; for, had the lady been angered by such a trifle, it would have been easy to appease her."

"Nay," said Ennasuite, "perhaps she would not then have consented."

"And pray," said Saffredent, "would it not have been easy enough to compel her, since she had herself given him the opportunity?"

"By Our Lady!" said Nomerfide, "how you run on! Is that the way to win the favour of a lady who is accounted virtuous and discreet?"

"In my opinion," said Saffredent, "the highest honour that can be paid to a woman from whom such things are desired is to take her by force, for there is not the pettiest damsel among them but seeks to be long entreated. Some indeed there are who must receive many gifts before they are won, whilst there are others so stupid that hardly any device or craft can enable one to win them, and with these one must needs be ever thinking of some means or other. But when you have to do with a woman who is too clever to be deceived, and too virtuous to be gained by words or gifts, is there not good reason to employ any means whatever that may be at your disposal to vanquish her? When you hear it said that a man has taken a woman by force, you may be sure that the woman has left him hopeless of any other means succeeding, and you should not think any the worse of a man who has risked his life in order to give scope to his love."

Geburon burst out laughing.

"In my day," said he, "I have seen besieged places stormed because it was impossible to bring the garrison to a parley either by money or by threats; 'tis said that a place which begins to treat is half taken."

"You may think," said Ennasuite, "that every love on earth is based upon such follies as these, but there are those who have loved, and who have long persevered in their love, with very different aims."

"If you know a story of that kind," said Hircan, "I will give place to you for the telling of it."

"I do know one," said Ennasuite, "and I will very willingly relate it."

Footnotes:

- This story seems to be based on fact, being corroborated in its main lines by Brantôme, but there is nothing in the narrative to admit of the personages referred to being identified.—Ed.

- Brantôme's Dames Galantes contains an anecdote which is very similar in character to this tale: "I have heard speak," he writes, "of a very beautiful and honourable lady, who gave her lover an assignation to sleep with her, on the condition that he should not touch her... and he actually obeyed her, remaining in a state of ecstasy, temptation and continence the whole night long; whereat she was so well pleased with him that some time afterwards she consented to become his mistress, giving as her reason that she had wished to prove his love by his obedience to her injunctions; and on this account she afterwards loved him the more, for she felt sure that he was capable of even a greater feat than this, though it were a very great one."— Lalanne's OEuvres de Brantôme, vol. ix. pp. 6, 7.—L.

- In reference to this story, Montaigne says in his Essay on Cruelty: "Such as have sensuality to encounter, willingly make use of this argument, that when it is at the height it subjects us to that degree that a man's reason can have no access... wherein they conceive that the pleasure doth so transport us that our reason cannot perform its office whilst we are so benumbed and extacied in delight.... But I know that a man may triumph over the utmost effort of this pleasure: I have experienced it in myself, and have not found Venus so imperious a goddess as many—and some more reformed than I—declare. I do not consider it as a miracle, as the Queen of Navarre does in one of the Tales of her Heptameron (which is a marvellous pretty book of the kind), nor for a thing of extreme difficulty to pass over whole nights, where a man has all the convenience and liberty he can desire, with a long-coveted mistress, and yet be just to his faith first given to satisfy himself with kisses and innocent embraces only, without pressing any further."—Cotton's "Montaigne's Essays", London, 1743, vol ii. pp. 109-10.

- This is an allusion to the penalties pronounced by several ecclesiastical Councils, and specified in the Capitularies, against those who endeavoured to suspend the procreative faculties of their enemies by resorting to magic. On this matter Baluze's collection of Capitularies (vol. i.) may be consulted. The "chapter" referred to by Margaret is evidently chapter xv. (book vi.) of the Decretals of Pope Boniface VIII., which bears the title of De frigidis et maleficiatis, and which is alluded to by Rabelais in Pantagruel. The belief in the practices in question dates back to ancient times, and was shared by Plato and Pliny, the latter of whom says that to guard against any spell of the kind some wolf fat should be rubbed upon the threshold and door jambs of one's bed-chamber. In the sixteenth century sorcery of this description was so generally believed in, in some parts of France, that Cardinal du Perron inserted special prayers against it in the ritual. Some particulars on the subject will be found in the Admirables Secrets du Petit Albert, and also in a Traité d'Enchantement, published at La Rochelle in 1591, which gives details concerning certain practices alleged to take place on the solemnisation of marriage among those of the Reformed Church.—D. and L.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.