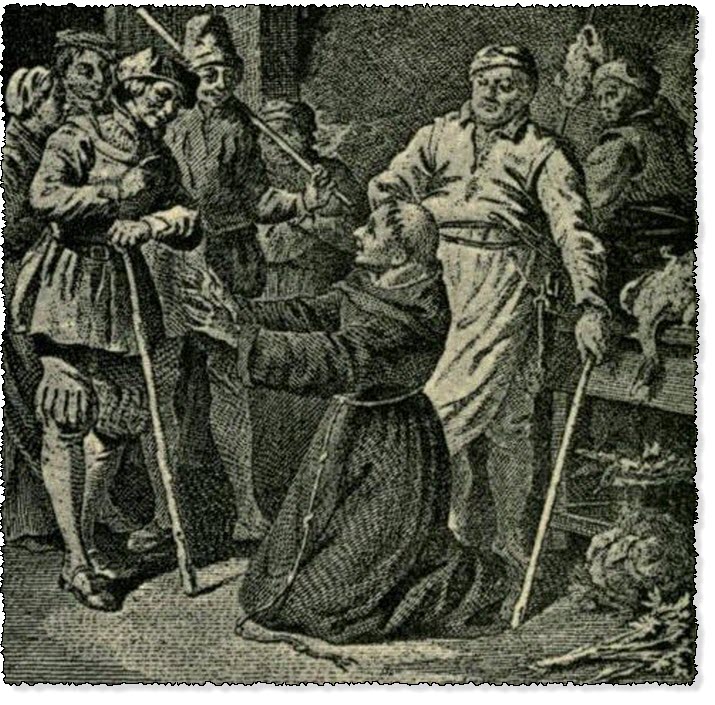

the Beating of The Wicked Grey Friar

The Heptameron - Day 5 - Tale 41 - the Beating of The Wicked Grey Friar

Summary of the First Tale Told on the Fifth of the Heptameron

Tale 41 of the Heptameron

In the year when my Lady Margaret of Austria came to Cambray on behalf of her nephew the Emperor, to treat of peace between him and the Most Christian King, who on his part was represented by his mother, my Lady Louise of Savoy, (1) the said Lady Margaret had in her train the Countess of Aiguemont, (2) who won, among this company, the renown of being the most beautiful of all the Flemish ladies.

When this great assembly separated, the Countess of Aiguemont returned to her own house, and, Advent being come, sent to a monastery of Grey Friars to ask for a clever preacher and virtuous man, as well to preach as to confess herself and her whole household. The Warden, remembering the great benefits that the Order received from the house of Aiguemont and that of Fiennes, to which the Countess belonged, sought out the man whom he thought most worthy to fill the said office.

Accordingly, as the Grey Friars more than any other order desire to obtain the esteem and friendship of great houses, they sent the most important preacher of their monastery, and throughout Advent he did his duty very well, and the Countess was well pleased with him.

On Christmas night, when the Countess desired to receive her Creator, she sent for her confessor, and after making confession in a carefully closed chapel, she gave place to her lady of honour, who in her turn, after being shriven, sent her daughter to pass through the hands of this worthy confessor. When the maiden had told all that was in her mind, the good father knew something of her secrets, and this gave him the desire and the boldness to lay an unwonted penance upon her.

"My daughter," said he, "your sins are so great that to atone for them I command you the penance of wearing my cord upon your naked flesh."

The maiden, who was unwilling to disobey him, made answer—

"Give it to me, father, and I will not fail to wear it."

"My daughter," said the good father, "it will be of no avail from your own hand. Mine, from which you shall receive absolution, must first bind it upon you; then shall you be absolved of all your sins."

The maiden replied, weeping, that she would not suffer it.

"What?" said the confessor. "Are you a heretic, that you refuse the penances which God and our holy mother Church have ordained?"

Heptameron Story 41

"I employ confession," said the maiden, "as the Church commands, and I am very willing to receive absolution and do penance. But I will not be touched by your hands, and I refuse this mode of penance."

"Then," said the confessor, "I cannot give you absolution."

The maiden rose from before him greatly troubled in conscience, for, being very young, she feared lest she had done wrong in thus refusing to obey the worthy father.

When mass was over and the Countess of Aiguemont had received the "Corpus Domini," her lady of honour, desiring to follow her, asked her daughter whether she was ready. The maiden, weeping, replied that she was not shriven.

"Then what were you doing so long with the preacher?" asked her mother.

"Nothing," said the maiden, "for, as I refused the penance that he laid upon me, he on his part refused me absolution."

Making prudent inquiry, the mother learnt the extraordinary penance that the good father had chosen for her daughter; and then, having caused her to be confessed by another, they received the sacrament together. When the Countess was come back from the church, the lady of honour made complaint to her of the preacher, whereupon the Countess was the more surprised and grieved, since she had thought so well of him. Nevertheless, despite her anger, she could not but feel very much inclined to laugh at the unwonted nature of the penance.

Still her laughter did not prevent her from having the friar taken and beaten in her kitchen, where he was brought by the strokes of the rod to confess the truth; and then she sent him bound hand and foot to his Warden, begging the latter for the future to commission more virtuous men to preach the Word of God.

"Consider, ladies, if the monks be not afraid to display their wantonness in so illustrious a house, what may they not do in the poor places where they commonly make their collections, and where opportunities are so readily offered to them, that it is a miracle if they are quit of them without scandal. And this, ladies, leads me to beg of you to change your ill opinion into compassion, remembering that he (3) who blinds the Grey Friars is not sparing of the ladies when he finds an opportunity."

"Truly," said Oisille, "this was a very wicked Grey Friar. A monk, a priest and a preacher to work such wickedness, and that on Christmas day, in the church and under the cloak of the confessional—all these are circumstances which heighten the sin."

"It would seem from your words," said Hircan, "that the Grey Friars ought to be angels, or more discreet than other men, but you have heard instances enough to show you that they are far worse. As for the monk in the story, I think he might well be excused, seeing that he found himself shut up all alone at night with a handsome girl."

"True," said Oisille, "but it was Christmas night."

"That makes him still less to blame," said Simontault, "for, being in Joseph's place beside a fair virgin, he wished to try to beget an infant and so play the Mystery of the Nativity to the life."

"In sooth," said Parlamente, "if he had thought of Joseph and the Virgin Mary, he would have had no such evil purpose. At all events, he was a wickedly-minded man to make so evil an attempt upon such slight provocation."

"I think," said Oisille, "that the Countess punished him well enough to afford an excellent example to his fellows."

"But 'tis questionable," said Nomerfide, "whether she did well in thus putting her neighbour to shame, or whether 'twould not have been better to have quietly shown him his faults, rather than have made them so publicly known."

"That would, I think, have been better," said Geburon, "for we are commanded to rebuke our neighbour in secret, before we speak of the matter to any one else or to the Church. When a man has been brought to public disgrace, he will hardly ever be able to mend his ways, but fear of shame withdraws as many persons from sin as conscience does."

"I think," said Parlamente, "that we ought to observe the teaching of the Gospel towards all except those that preach the Word of God and act contrary to it. We should not be afraid to shame such as are accustomed to put others to shame; indeed I think it a very meritorious thing to make them known for what they really are, so that we take not a mock stone (4) for a fine ruby. But to whom will Saffredent give his vote?"

"Since you ask me," he replied, "I will give it to yourself, to whom no man of understanding should refuse it."

"Then, since you give it to me, I will tell you a story to the truth of which I can myself testify. I have always heard that when virtue abides in a weak and feeble vessel, and is assailed by its strong and puissant opposite, it especially deserves praise, and shows itself to be what it really is. If strength withstand strength, it is no very wonderful thing; but if weakness win the victory, it is lauded by every one. Knowing, as I do, the persons of whom I desire to speak, I think that I should do a wrong to virtue, (which I have often seen hidden under so mean a covering that none gave it any heed), if I did not tell of her who performed the praiseworthy actions that I now feel constrained to relate."

Footnotes:

- It was in June 1529 that Margaret of Austria came to Cambrai to treat for peace, on behalf of Charles V. Louise of Savoy, who represented Francis I., was accompanied on this occasion by her daughter, Queen Margaret, who appears to have taken part in the conferences. The result of these was that the Emperor renounced his claims on Burgundy, but upheld all the other stipulations of the treaty of Madrid. Having been brought about entirely by feminine negotiators, the peace of Cambrai acquired the name of "La Paix des Dames," or "the Ladies' Peace." Some curious particulars of the ceremonies observed at Cambrai on this occasion will be found in Leglay's Notice sur les fêles et cérémonies à Cambray depuis le XIe siècle, Cambrai, 1827.—L. and B. J.

- This is Frances of Luxemburg, Baroness of Fiennes and Princess of Gavre, wife of John IV., Count of Egmont, chamberlain to the Emperor Charles V. They were the parents of the famous Lamoral Count of Egmont, Prince of Gavre and Baron of Fiennes, born in 1522 and put to death by the Duke of Alba on June 5, 1568.—B.J.

- The demon.—B. J.

- The French word here is doublet. The doublet was a piece of crystal, cut after the fashion of a diamond, and backed with red wax so as to give it somewhat the colour of a ruby.—B. J.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.