The Heptameron - Day 5 - Tale 46

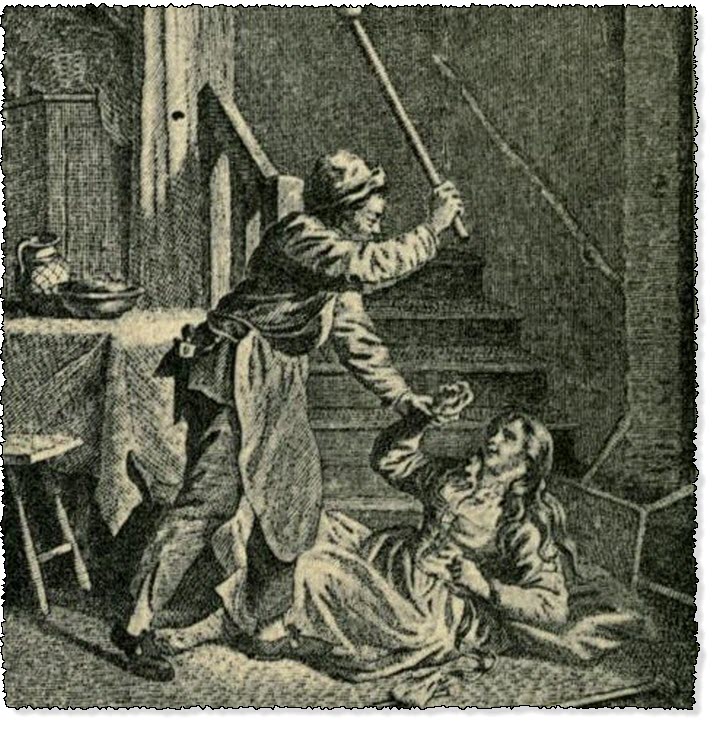

The Heptameron - Day 5 - Tale 46 - the Young Man Beating his Wife

Summary of the Sixth Tale Told on the Fifth of the Heptameron

Tale 46 of the Heptameron

In the town of Angoulême, where Count Charles, father of King Francis, often abode, there dwelt a Grey Friar named De Vale, the same being held a learned man and a great preacher. One Advent this Friar preached in the town in presence of the Count, whereby he won such renown that those who knew him eagerly invited him to dine at their houses. Among others that did this was the Judge of the Exempts (2) of the county, who had wedded a beautiful and virtuous woman. The Friar was dying for love of her, yet lacked the hardihood to tell her so; nevertheless she perceived the truth, and held him in derision.

After he had given several tokens of his wanton purpose, he one day espied her going up into the garret alone. Thinking to surprise her, he followed, but hearing his footsteps she turned and asked whither he was going. "I am going after you," he replied, "to tell you a secret."

"Nay, good father," said the Judge's wife. "I will have no secret converse with such as you. If you come up any higher, you will be sorry for it."

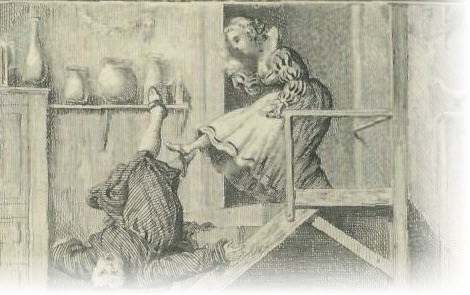

Seeing that she was alone, he gave no heed to her words, but hastened up after her. She, however, was a woman of spirit, and when she saw the Friar at the top of the staircase, she gave him a kick in the stomach, and with the words, "Down! down! sir," (3) cast him from the top to the bottom. The poor father was so greatly ashamed at this, that, forgetting the hurt he had received in falling, he fled out of the town as fast as he was able. He felt sure that the lady would not conceal the matter from her husband; and indeed she did not, nor yet from the Count and Countess, so that the Friar never again durst come into their presence.

To complete his wickedness, he repaired to the house of a lady who preferred the Grey Friars to all other folk, and, after preaching a sermon or two before her, he cast his eyes upon her daughter, who was very beautiful. And as the maiden did not rise in the morning to hear his sermon, he often scolded her in presence of her mother, whereupon the latter would say to him—"Would to God, father, that she had some taste of the discipline which you monks receive from one another."

The good father vowed that if she continued to be so slothful, he would indeed give her some of it, and her mother earnestly begged him to do so.

Heptameron Story 46

A day or two afterwards, he entered the lady's apartment, and, not seeing her daughter there, asked her where she was.

"She fears you so little," replied the lady, "that she is still in bed."

"There can be no doubt," said the Grey Friar, "that it is a very evil habit in young girls to be slothful. Few people think much of the sin of sloth, but for my part, I deem it one of the most dangerous there is, for the body as for the soul. You should therefore chastise her for it, and if you will give me the matter in charge, I will take good care that she does not lie abed at an hour when she ought to be praying to God."

The poor lady, believing him to be a virtuous man, begged him to be kind enough to correct her daughter, which he at once agreed to do, and, going up a narrow wooden staircase, he found the girl all alone in bed. She was sleeping very soundly, and while she slept he lay with her by force. The poor girl, waking up, knew not whether he were man or devil, but began to cry out as loudly as she could, and to call for help to her mother. But the latter, standing at the foot of the staircase, cried out to the Friar—"Have no pity on her, sir. Give it to her again, and chastise the naughty jade."

When the Friar had worked his wicked will, he came down to the lady and said to her with a face all afire—"I think, madam, that your daughter will remember my discipline."

The mother thanked him warmly and then went upstairs, where she found her daughter making such lamentation as is to be expected from a virtuous woman who has suffered from so foul a crime. On learning the truth, the mother had search made everywhere for the Friar, but he was already far away, nor was he ever afterwards seen in the kingdom of France.

"You see, ladies, with how much security such commissions may be given to those that are unfit for them. The correction of men pertains to men and that of women to women; for women in the correction of men would be as pitiful as men in the correction of women would be cruel."

"Jesus! madam," said Parlamente, "what a base and wicked Friar!"

"Say rather," said Hircan, "what a foolish and witless mother to be led by hypocrisy into allowing so much familiarity to those who ought never to be seen except in church."

"In truth," said Parlamente, "I acknowledge that she was the most foolish mother imaginable; had she been as wise as the Judge's wife, she would rather have made him come down the staircase than go up. But what can you expect? The devil that is half-angel is the most dangerous of all, for he is so well able to transform himself into an angel of light, that people shrink from suspecting him to be what he really is; and it seems to me that persons who are not suspicious are worthy of praise."

"At the same time," said Oisille, "people ought to suspect the evil that is to be avoided, especially those who hold a trust; for it is better to suspect an evil that does not exist than by foolish trustfulness to fall into one that does. I have never known a woman deceived through being slow to believe men's words, but many are there that have been deceived through being over prompt in giving credence to falsehood. Therefore I say that possible evil cannot be held in too strong suspicion by those that have charge of men, women, cities or states; for, however good the watch that is kept, wickedness and treachery are prevalent enough, and the shepherd who is not vigilant will always be deceived by the wiles of the wolf."

"Still," said Dagoucin, "a suspicious person cannot have a perfect friend, and many friends have been divided by suspicion."

"If you know any such instance," said Oisille, "I give you my vote that you may relate it."

"I know one," said Dagoucin, "which is so strictly true that you will needs hear it with pleasure. I will tell you, ladies, when it is that a close friendship is most easily severed; 'tis when the security of friendship begins to give place to suspicion. For just as trust in a friend is the greatest honour that can be shown him, so is doubt of him a still greater dishonour. It proves that he is deemed other than we would have him to be, and so causes many close friendships to be broken off, and friends to be turned into foes. This you will see from the story that I am minded to relate."

TALE XLVI.(B).

Concerning a Grey Friar who made it a great crime on the part of husbands to beat their wives. (4)In the town of Angoulême, where Count Charles, father of King Francis, often abode, there dwelt a Grey Friar named De Vallès, (52) the same being a learned man and a very great preacher. At Advent time this Friar preached in the town in presence of the Count, whereby his reputation was still further increased.

It happened also that during Advent a hare-brained young fellow, who had married a passably handsome young woman, continued none the less to run at the least as dissolute a course as did those that were still bachelors. The young wife, being advised of this, could not keep silence upon it, so that she very often received payment after a different and a prompter fashion than she could have wished. For all that, she ceased not to persist in lamentation, and sometimes in railing as well; which so provoked the young man that he beat her even to bruises and blood. Thereupon she cried out yet more loudly than before; and in a like fashion all the women of the neighbourhood, knowing the reason of this, could not keep silence, but cried out publicly in the streets, saying—

"Shame, shame on such husbands! To the devil with them!"

By good fortune the Grey Friar De Vallès was passing that way and heard the noise and the reason of it. He resolved to touch upon it the following day in his sermon, and did so. Turning his discourse to the subject of marriage and the affection which ought to subsist in it, he greatly extolled that condition, at the same time censuring those that offended against it, and comparing wedded to parental love. Among other things, he said that a husband who beat his wife was in more danger, and would have a heavier punishment, than if he had beaten his father or his mother.

"For," said he, "if you beat your father or your mother you will be sent for penance to Rome; but if you beat your wife, she and all the women of the neighbourhood will send you to the devil, that is, to hell. Now look you what a difference there is between these two penances. From Rome a man commonly returns again, but from hell, oh! from that place, there is no return: nulla est redemptio" (6)

After preaching this sermon, he was informed that the women were making a triumph of it, (7) and that their husbands could no longer control them. He therefore resolved to set the husbands right just as he had previously assisted their wives.

With this intent, in one of his sermons he compared women and devil together, saying that these were the greatest enemies that man had, that they tempted him without ceasing, and that he could not rid himself of them, especially of women.

"For," said he, "as far as devils are concerned, if you show them the cross they flee away, whereas women, on the contrary, are tamed by it, and are made to run hither and thither and cause their husbands countless torments. But, good people, know you what you must do? When you find your wives afflicting you thus continually, as is their wont, take off the handle of the cross and with it drive them away. You will not have made this experiment briskly three or four times before you will find yourselves the better for it, and see that, even as the devil is driven off by the virtue of the cross, so can you drive away and silence your wives by virtue of the handle, provided only that it be not attached to the cross aforesaid."

"You have here some of the sermons by this reverend De Vallès, of whose life I will with good reason relate nothing more. However, I will tell you that, whatever face he put upon the matter—and I knew him—he was much more inclined to the side of the women than to that of the men."

"Yet, madam," said Parlamente, "he did not show this in his last sermon, in which he instructed the men to ill-treat them."

"Nay, you do not comprehend his artifice," said Hircan. "You are not experienced in war and in the use of the stratagems that it requires; among these, one of the most important is to kindle strife in the camp of the enemy, whereby he becomes far easier to conquer. This master monk well knew that hatred and wrath between husband and wife most often cause a loose rein to be given to the wife's honour. And when that honour frees itself from the guardianship of virtue, it finds itself in the power of the wolf before it knows even that it is astray."

"However that may be," said Parlamente, "I could not love a man who had sown such division between my husband and myself as would lead even to blows; for beating banishes love. Yet, by what I have heard, they [the friars] can be so mincing when they seek some advantage over a woman, and so attractive in their discourse, that I feel sure there would be more danger in hearkening to them in secret than in publicly receiving blows from a husband in other respects a good one."

"Truly," said Dagoucin, "they have so revealed their plottings in all directions, that it is not without reason that they are to be feared; (8) although in my opinion persons who are not suspicious are worthy of praise."

"At the same time," said Oisille, "people ought to suspect the evil that is to be avoided, for it is better to suspect an evil that does not exist than by foolish trustfulness to fall into one that does. For my part, I have never known a woman deceived by being slow to believe men's words, but many are through being too prompt in giving credence to falsehood. Therefore I say that possible evil cannot be too strongly suspected by those that have charge of men, women, cities or states; for, however good may be the watch that is kept, wickedness and treachery are prevalent enough, and for this reason the shepherd who is not vigilant will always be deceived by the wiles of the wolf."

"Still," said Dagoucin, "a suspicious person cannot have a perfect friend, and many friends have been parted by bare suspicion."

"If you should know any such instance," thereupon said Oisille, "I will give you my vote that you may relate it."

"I know one," said Dagoucin, "which is so strictly true that you will hear it with pleasure. I will tell you, ladies, when it is that close friendship is most readily broken off; it is when the security of friendship begins to give place to suspicion. For just as to trust a friend is the greatest honour one can do him, so is doubt of him the greatest dishonour, inasmuch as it proves that he is deemed other than one would have him to be, and in this wise many close friendships are broken off and friends turned into foes. This you will see from the story that I am now about to relate."

Footnotes:

- Boaistuau and Gruget omit this tale, and the latter replaces it by that numbered XLVI. (B). Count Charles of Angoulême having died on January i, 1496, the incidents related above must have occurred at an earlier date.—L.

- The Exempt was a police officer, and the functions of the Juge des Exempts were akin to those of a police magistrate.—Ed.

- The French words here are "Dévaliez, dévaliez, monsieur," whilst MS. No. 1520 gives, "Monsieur de Vale, dévalés." In either case there is evidently a play upon the friar's name, which was possibly pronounced Vallès or Vallès. Adrien de Valois, it maybe pointed out, rendered his name in Latin as Valesius; the county of Valois and that of Valais are one and the same; we continue calling the old French kings Valois, as their name was written, instead of Valais as it was pronounced, as witness, for instance, the nickname given to Henry III. by the lampooners of the League, "Henri dévalé." See also post, Tale XLVI. (B), note 2.—M. and Ed.

- This is the tale inserted in Gruget's edition in lieu of the previous one.—Ed.

- We had thought that Friar Vallès might possibly be Robert de Valle, who at the close of the fifteenth century wrote a work entitled Explanatio in Plinium, but find that this divine was a Bishop of Rouen, and never belonged to the Grey Friars. In Gessner's Biographia Universalis, continued by Frisius, mention is made of three learned ecclesiastics of the name of Valle living in or about Queen Margaret's time: Baptiste de Valle, who wrote on war and duelling; William de Valle, who penned a volume entitled De Anima Sorbono; and Amant de Valle, a Franciscan minorité born at Toulouse, who was the author of numerous philosophical works, the most important being Elucidationes Scoti.—B. J.

- This was the Pope's expression apropos of Messer Biagio, whom Michael Angelo had introduced into his "Last Judgment."—M.

- The French expression is faisaient leur Achilles, the nearest equivalent to which in English would probably be "Hectoring" It is curious that the French should have taken the name of Achilles and we that of Hector to express the same idea of arrogance and bluster.—Ed.

- From this point the dialogue is almost word for word the same as that following Tale XLVI. (A).—Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.