the Countess Facing Her Lovers

The Heptameron - Day 5 - Tale 49 - the Countess Facing Her Lovers

Summary of the Ninth Tale Told on the Fifth of the Heptameron

Tale 49 of the Heptameron

At the Court of King Charles—which Charles I shall not mention, for the sake of the lady of whom I wish to speak, and whom I shall not call by her own name—there was a Countess of excellent lineage, (2) but a foreigner. And as novelties ever please, this lady, both for the strangeness of her attire and for its exceeding richness, was observed by all. Though she was not to be ranked among the most beautiful, she possessed gracefulness, together with a noble assurance that could not be surpassed; and, moreover, her manner of speech and her seriousness were to match, so that there was none but feared to accost her excepting the King, who loved her exceedingly. That he might have still more intimate converse with her, he gave some mission to the Count, her husband, which kept him away for a long time, and meanwhile the King made right good cheer with his wife.

Several of the King's gentlemen, knowing that their master was well treated by her, took courage to speak to her, and among the rest was one called Astillon, (3) a bold man and graceful of bearing.

At first she treated him so seriously, threatening to tell of him to the King his master, that he well-nigh became afraid of her. However, as he had not been wont to fear the threats even of the most redoubtable captains, he would not suffer himself to be moved by hers, but pressed her so closely that she at last consented to speak with him in private, and taught him the manner in which he should come to her apartment. This he failed not to do, and, in order that the King might be without suspicion of the truth, he craved permission to go on a journey, and set out from the Court. On the very first day, however, he left all his following and returned at night to receive fulfilment of the promises that the Countess had made him. These she kept so much to his satisfaction, that he was content to remain shut up in a closet for five or six days, without once going out, and living only on restoratives.

During the week that he lay in hiding, one of his companions called Durassier (4) made love to the Countess. At the beginning she spoke to this new lover, as she had spoken to the first, with harsh and haughty speech that grew milder day by day, insomuch that when the time was come for dismissing the first prisoner, she put the second into his place. While he was there, another companion of his, named Valnebon, (5) did the same as the former two, and after these there came yet two or three more to lodge in the sweet prison.

This manner of life continued for a long time, and was so skilfully contrived that none of the lovers knew aught of the others; and although they were aware of the love that each of them bore the lady, there was not one but believed himself to be the only successful suitor, and laughed at his comrades who, as he thought, had failed to win such great happiness.

One day when the gentlemen aforesaid were at a banquet where they made right good cheer, they began to speak of their several fortunes and of the prisons in which they had lain during the wars. Valnebon, however, who found it a hard task to conceal the great good fortune he had met with, began saying to his comrades—

"I know not what prisons have been yours, but for my own part, for love of one wherein I once lay, I shall all my life long give praise and honour to the rest. I think that no pleasure on earth comes near that of being kept a prisoner."

Astillon, who had been the first captive, had a suspicion of the prison that he meant, and replied—

"What gaoler, Valnebon, man or woman, treated you so well that you became so fond of your prison?"

"Whoever the gaoler may have been," said Valnebon, "my prisonment was so pleasant that I would willingly have had it last longer. Never was I better treated or more content."

Durassier, who was a man of few words, clearly perceived that they were discussing the prison in which he had shared like the rest; so he said to Valnebon—

"On what meats were you fed in the prison that you praise so highly?"

"What meats?" said Valnebon. "The King himself has none better or more nourishing."

"But I should also like to know," said Durassier, "whether your keeper made you earn your bread properly?"

Valnebon, suspecting that he had been understood, could not hold from swearing.

"God's grace!" said he. "Had I indeed comrades where I believed myself alone?"

Perceiving this dispute, wherein he had part like the rest, Astillon laughed and said—

"We all serve one master, and have been comrades and friends from boyhood; if, then, we are comrades in the same good fortune, we can but laugh at it. But, to see whether what I imagine be true, pray let me question you, and do you confess the truth to me; for if that which I fancy has befallen us, it is as amusing an adventure as could be found in any book."

They all swore to tell the truth if the matter were such as they could not deny.

Then said he to them—

"I will tell you my own fortune, and you will tell me, ay or nay, if yours has been the same."

To this they all agreed, whereupon he said—

"I asked leave of the King to go on a journey."

"So," they replied, "did we."

"When I was two leagues from the Court, I left all my following and went and yielded myself up prisoner."

"We," they replied, "did the same."

"I remained," said Astillon, "for seven or eight days, and lay in a closet where I was fed on nothing but restoratives and the choicest viands that I ever ate. At the end of a week, those who held me captive suffered me to depart much weaker in body than I had been on my arrival."

They all swore that the like had happened to them.

"My imprisonment," said Astillon, "began on such a day and finished on such another."

"Mine," thereupon said Durassier, "began on the very day that yours ended, and lasted until such a day."

Valnebon, who was losing patience, began to swear.

"'Sblood!" said he, "from what I can see, I, who thought myself the first and only one, was the third, for I went in on such a day and came out on such another."

Three others, who were at the table, swore that they had followed in like order.

"Well, since that is so," said Astillon, "I will mention the condition of our gaoler. She is married, and her husband is a long way off."

"'Tis even she," they all replied.

Heptameron Story 49

"Well, to put us out of our pain," said Astillon, "I, who was first enrolled, shall also be the first to name her. It was my lady the Countess, she who was so extremely haughty that in conquering her affection I felt as though I had conquered Cæsar."

[Said Valnebon—(6)]

"To the devil with the jade, who gave us so much toil, and made us believe ourselves so fortunate in winning her! Never was there such wantonness, for while she kept one in hiding she was practising upon another, so that she might never be without diversion. I would rather die than suffer her to go unpunished."

Each thereupon asked him what he thought ought to be done to her, saying that they were all ready to do it.

"I think," said he, "that we ought to tell the King our master, who prizes her as though she were a goddess.

"By no means," said Astillon; "we are ourselves able to take vengeance upon her, without calling in the aid of our master. Let us all be present to-morrow when she goes to mass, each of us wearing an iron chain about his neck. Then, when she enters the church, we will greet her as shall be fitting."

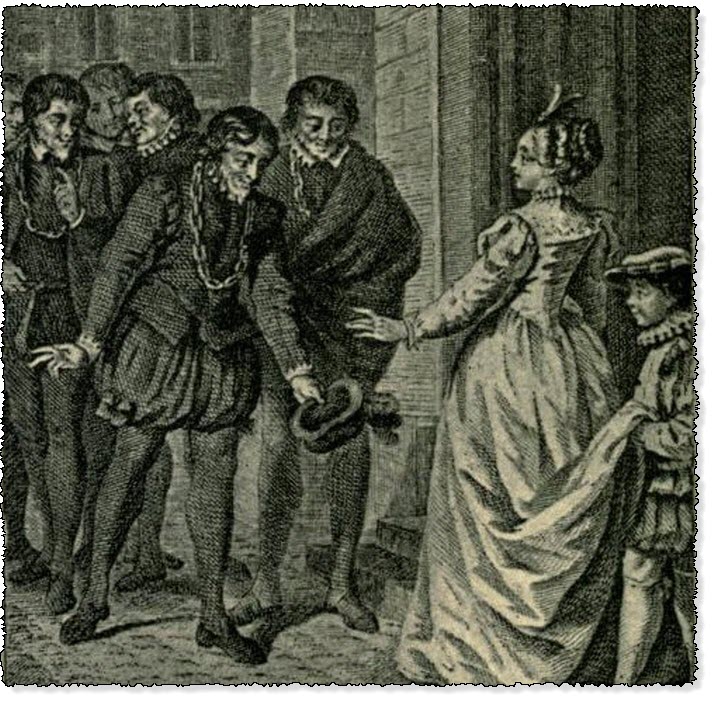

This counsel was highly approved by the whole company, and each provided himself with an iron chain. The next morning they all went, dressed in black and with their iron chains twisted like collars round their necks, to meet the Countess as she was going to church. And as soon as she saw them thus attired, she began to laugh and asked them—

"Whither go such doleful folk?"

"Madam," said Astillon, "we are come to attend you as poor captive slaves constrained to do your service."

The Countess, feigning not to understand, replied—

"You are not my captives, and I cannot understand that you have more occasion than others to do me service."

Thereupon Valnebon stepped forward and said to her—

"After eating your bread for so long a time, we should be ungrateful indeed if we did not serve you."

She made excellent show of not understanding the matter, thinking by this seriousness to confound them; but they pursued their discourse in such sort that she saw that all was discovered. So she immediately devised a means of baffling them, for, having lost honour and conscience, she would in no wise take to herself the shame that they thought to bring upon her. On the contrary, like one who set her pleasure before all earthly honour, she neither changed her countenance nor treated them worse than before, whereat they were so confounded, that they carried away in their own bosoms the shame they had thought to bring upon her.

"If, ladies, you do not consider this story enough to prove that women are as bad as men, I will seek out others of the same kind to relate to you. Nevertheless I think that this one will suffice to show you that a woman who has lost shame is far bolder to do evil than a man."

There was not a woman in the company that heard this story, who did not make as many signs of the cross as if all the devils in hell were before her eyes. However, Oisille said—

"Ladies, let us humble ourselves at hearing of so terrible a circumstance, and the more so as she who is forsaken by God becomes like him with whom she unites; for even as those who cleave to God have His spirit within them, so is it with those that cleave to His opposite, whence it comes that nothing can be more brutish than one devoid of the Spirit of God."

"Whatever the poor lady may have done," said Ennasuite, "I nevertheless cannot praise the men who boasted of their imprisonment."

"It is my opinion," said Longarine, "that a man finds it as troublesome to conceal his good fortune as to pursue it. There is never a hunter but delights to wind his horn over his quarry, nor lover but would fain have credit for his conquest."

"That," said Simontault, "is an opinion which I would hold to be heretical in presence of all the Inquisitors of the Faith, for there are more men than women that can keep a secret, and I know right well that some might be found who would rather forego their happiness than have any human being know of it. For this reason has the Church, like a wise mother, ordained men to be confessors and not women, seeing that the latter can conceal nothing."

"That is not the reason," said Oisille; "it is because women are such enemies of vice that they would not grant absolution with the same readiness as is shown by men, and would be too stern in their penances."

"If they were as stern in their penances," said Dagoucin, "as they are in their responses, they would reduce far more sinners to despair than they would draw to salvation; and so the Church has in every sort well ordained. But, for all that, I will not excuse the gentlemen who thus boasted of their prison, for never was a man honoured by speaking evil of a woman."

"Since they all fared alike," said Hircan, "it seems to me that they did well to console one another."

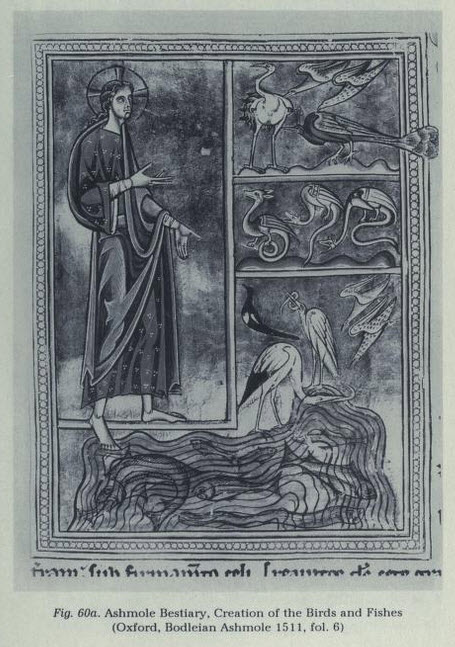

"Nay," said Geburon, "they should never have acknowledged it for the sake of their own honour. The books of the Round Table (7) teach us that it is not to the honour of a worthy knight to overcome one that is good for naught."

"I am amazed," said Longarine, "that the unhappy woman did not die of shame in presence of her captives."

"Those who have lost shame," said Oisille, "can hardly ever recover it, excepting, however, she that has forgotten it through deep love. Of such have I seen many return."

"I think," said Hircan, "that you must have seen the return of as many as went, for deep love in a woman is difficult to find."

"I am not of your opinion," said Longarine; "I think that there are some women who have loved to death."

"So exceedingly do I desire to hear a tale of that kind," said Hircan, "that I give you my vote in order to learn of a love in women that I had never deemed them to possess."

"Well, if you hearken," said Longarine, "you will believe, and will see that there is no stronger passion than love. But while it prompts one to almost impossible enterprises for the sake of winning some portion of happiness in this life, so does it more than any other passion reduce that man or woman to despair, who loses the hope of gaining what is longed for. This indeed you will see from the following story."

Footnotes:

- The incidents here related must have occurred during the reign of Charles VIII., probably in or about 1490.—L.

- This Countess cannot be identified. She was probably the wife of one of the many Italian noblemen, like the Caraccioli and San Severini, who entered the French service about the time of the conquest of Naples. Brantôme alludes to the story in his Dames Galantes (Fourth Discourse) but gives no names.—Ed.

- This is James de Chastillon, not, however, J. Gaucher de Chastillon, "King of Yvetot," as M. de Lincy supposes, but J. de Coligny-Chastillon, as has been pointed out by M. Frank. Brantôme devotes the Nineteenth Discourse of his Capitaines françois to this personage, and says: "He had been one of the great favourites and mignons of King Charles VIII., even at the time of the journey to the kingdom of Naples; and 'twas then said, 'Chastillon, Bourdillon and Bonneval [see post, note 5] govern the royal blood.'" Wounded in April 1512 at the battle of Ravenna, "the most bloody battle of the century," he was removed to Ferrara, where he died (May 25). He was the second husband of Blanche de Tournon, Lady of Honour to Queen Margaret, respecting whom see ante, vol. i. pp. 84-5, 122-4, and vol. iv. p. 144, note 2.—L., F. and Ed.

- This in all probability is the doughty James Galliot de Genouillac, who—much in the same way as in our own times the names of the "Iron Duke" and the "Man of Iron" have been bestowed on Wellington and Bismarck—was called by his contemporaries the "Seigneur d'Acier" or "Steel Lord," whence "Durassier"—hard steel. Born in Le Quercy in or about 1466, Genouillac accompanied Charles VIII. on his Italian expeditions, and, according to Brantôme, surpassed all others in valour and influence. He greatly distinguished himself at the battle of Fornova (1495), and in 1515 we find him one of the chief commanders of the French artillery. For the great skill he displayed at Marignano he was appointed Grand Master of the Artillery and Seneschal of Armagnac, and he subsequently became Grand Equerry of France. At Pavia, where he again commanded the artillery, he would have swept away the Spaniards had not the French impetuously charged upon them, preventing him from firing his pieces. Most of the latter he contrived to save, severe as was the defeat, and he effectually protected the retreat of the Duke of Alençon and the Count of Clermont into France. Genouillac died in 1546, a year after he had been appointed Governor of Languedoc.—B. J. and Ed.

- Valnebon is an anagram of the name Bonneval, and Queen Margaret evidently refers here to a member of the Bonneval family. In the time of Charles VIII. this illustrious Limousin house had two principal members, Anthony, one of the leading counsellors of that king (as of his predecessor Louis XI. and his successor Louis XII.), and Germain, also a royal counsellor and chamberlain. The heroes of the above story being military men and old friends and comrades, it is probable that the reference is to Germain de Bonneval, he, like Chastillon and Genouillac, having accompanied Charles VIII. on his expedition into Italy. Germain de Bonneval, moreover, was one of the seven noblemen who fought at the battle of Fornova, clad and armed exactly like the French king. He perished at the memorable defeat of Pavia in 1525. From him descended, in a direct line, the famous eighteenth century adventurer, Claud Alexander, Count de Bonneval.—B. J. and Ed.

- It is probable that the angry Valnebon is speaking here, and that his name has been accidentally omitted from the MSS. At all events the three subsequent paragraphs show that these remarks are not made by Astillon, who declines the other speaker's advice, and proposes a scheme of his own.— Ed.

- Queen Margaret was well acquainted with these (see ante, vol. iii. p. 48). In a list drawn up after her father's death, of the two hundred volumes of books in his library, a most remarkable one for the times, we find specified several copies of "Lancelot," "Tristan," &c, some in MS. with miniatures and illuminated letters, and others printed on parchment. Besides numerous religious writings, volumes of Aristotle, Ovid, Mandeville, Dante, the Chronicles of St. Denis, and the "Book of the Great Khan, bound in cloth of gold," the library contained various works of a character akin to that of the Heptameron. For instance, a copy of the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles in print; a French translation of Poggio's Facetio, also in print, and two copies of Boccaccio in MS., one of them bound in purple velvet, and richly illuminated, each page having a border of blue and silver. This last if still in existence would be very valuable.—Eu.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.