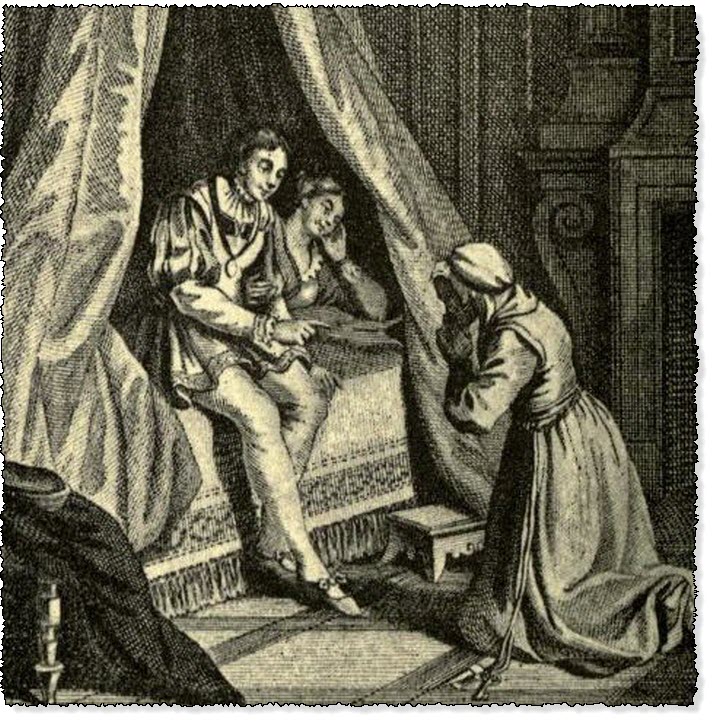

The Old Serving-woman Explaining Her Mistake To The Duke and Duchess of Vendôme

The Heptameron - Day 7 - Tale 66 - The Old Serving-woman Explaining Her Mistake To The Duke and Duchess of Vendôme

bobocontentSummary of the Sixth Tale Told on the Seventh of the Heptameron

Tale 66 of the Heptameron

In the year when the Duke of Vendôme married the Princess of Navarre, (1) the King and Queen, their parents, after feasting at Vendôme, went with them into Guienne, and, visiting a gentleman's house where there were many honourable and beautiful ladies, the newly married pair danced so long in this excellent company that they became weary, and, withdrawing to their chamber, lay down in their clothes upon the bed and fell asleep, doors and windows being shut and none remaining with them.

Just, however, when their sleep was at its soundest, they were awakened by their door being opened from without, and the Duke drew the curtain and looked to see who it might be, suspecting indeed that it was one of his friends who was minded to surprise him. But he perceived a tall, old bed-chamber woman come in and walk straight up to their bed, where, for the darkness of the room, she could not recognise them. Seeing them, however, quite close together, she began to cry out—

"Thou vile and naughty wanton! I have long suspected thee to be what thou art, yet for lack of proof spoke not of it to my mistress. But now thy vileness is so clearly shown that I shall in no sort conceal it; and thou, foul renegade, who hast wrought such shame in this house by the undoing of this poor wench, if it were not for the fear of God, I would e'en cudgel thee where thou liest. Get up, in the devil's name, get up, for methinks even now thou hast no shame."

The Duke of Vendôme and the Princess hid their faces against each other in order to have the talk last longer, and they laughed so heartily that they were not able to utter a word. Finding that for all her threats they were not willing to rise, the serving-woman came closer in order to pull them by the arms. Then she at once perceived both from their faces and from their dress that they were not those whom she sought, and, recognising them, she flung herself upon her knees, begging them to pardon her error in thus robbing them of their rest.

But the Duke of Vendôme was not content to know so little, and rising forthwith, he begged the old woman to say for whom she had taken them. This at first she was not willing to do; but at last, after he had sworn to her never to reveal it, she told him that there was a girl in the house with whom a prothonotary (2) was in love, and that she had long kept a watch on them, since it pleased her little to see her mistress trusting in a man who was working this shame towards her. She then left the Prince and Princess shut in as she had found them, and they laughed for a long while over their adventure. And, although they afterwards told the story they would never name any of the persons concerned.

"You see, ladies, how the worthy dame, whilst thinking to do a fine deed of justice, made known to strange princes a matter of which the servants of the house had never heard."

Heptameron Story 66

"I think I know," said Parlamente, "in whose house it was, and who the prothonotary is; for he has governed many a lady's house, and when he cannot win the mistress's favour he never fails to have that of one of the maids. In other matters, however, he is an honourable and worthy man."

"Why do you say 'in other matters'?" said Hircan. "Tis for that very behaviour that I deem him so worthy a man."

"I can see," said Parlamente, "that you know the sickness and the sufferer, and that, if he needed excuse, you would not fail him as advocate. Yet I would not trust myself to a man who could not contrive his affairs without having them known to the serving-women."

"And do you imagine," said Nomerfide, "that men care whether such a matter be known if only they can compass their end? You may be sure that, even if none spoke of it but themselves, it would still of necessity be known."

"They have no need," said Hircan angrily, "to say all that they know."

"Perhaps," she replied, blushing, "they would not say it to their own advantage."

"Judging from your words," said Simontault, "it would seem that men delight in hearing evil spoken about women, and I am sure that you reckon me among men of that kind. I therefore greatly wish to speak well of one of your sex, in order that I may not be held a slanderer by all the rest."

"I give you my place," said Ennasuite, "praying you withal to control your natural disposition, so that you may acquit yourself worthily in our honour."

Forthwith Simontault began—

"Tis no new thing, ladies, to hear of some virtuous act on your part which, methinks, should not be hidden but rather written in letters of gold, that it may serve women as an example, and give men cause for admiration at seeing in the weaker sex that from which weakness is prone to shrink. I am prompted, therefore, to relate something that I heard from Captain Robertval and divers of his company."

Footnotes:

- It was in October 1548, some eighteen months after Henry II. had succeeded Francis I., that Anthony de Bourbon, Duke of Vendôme, who after the King's children held the first rank in France, was married at Moulins to Margaret's daughter Jane of Navarre. The Duke was then thirty and Jane twenty years old. "I never saw so joyous a bride," wrote Henry II. to Montmorency, "she never does anything but laugh." She was indeed well pleased with the match, the better so, perhaps, as her husband had settled 100,000 livres on her, a gift which was the more acceptable by reason of her extravagant tastes and love of display. Ste. Marthe, in his Oraison Funèbre on Queen Margaret, speaks of her daughter's marriage as "a most fortunate conjunction," and refers to her son-in-law as "the most valiant and magnanimous Prince Anthony, Duke of Vendôme, whose admirable virtues have so inclined all France to love and revere him, that princes and nobles, the populace, the great and the humble alike, no sooner hear his name mentioned than they forthwith wish him and beg God to bestow on him all possible health and prosperity."—Ed

- The office of apostolic prothonotary was instituted by Pope Clement I., there being at first twelve such officers, whose duty was to write the lives of the saints and other apostolic records. Gradually their number so increased, that in the fifteenth century the title of prothonotary had come to be merely an honorary dignity, conferred as a matter of course on doctors of theology of noble family, or otherwise of note. In the role of Francis I.'s household for 1522, we find but one prothonotary mentioned, but in that for 1529 there are twelve. More than one of them might have been called un letrado que no tenia muchas letras, as Brantôme wrote of Thomas de Lescun, Prothonotary of Foix and afterwards Marshal of France. "In those days," adds the author of Les Grands Capitaines Français, "it was usual for prothonotaries and even for those of good family not to have much learning, but to enjoy themselves, hunt, make love and seduce the wives of the poor gentlemen who were gone to the wars."—OEuvres complètes de Brantôme, 8vo edit., vol. ii. p. 144.—L. and Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.