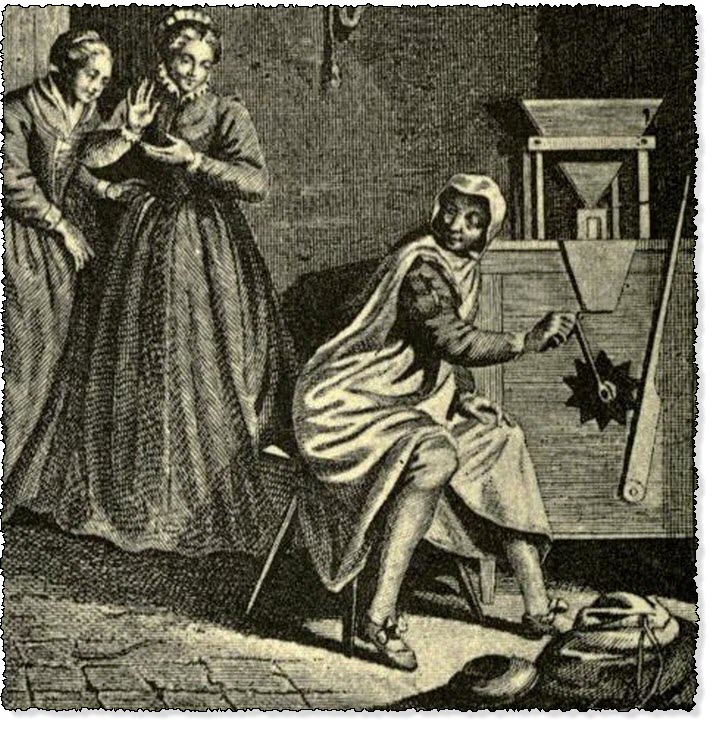

The Wife Discovering Her Husband in The Hood Of Their Serving-maid

The Heptameron - Day 7 - Tale 69 - The Wife Discovering Her Husband in The Hood Of Their Serving-maid

Summary of the Ninth Tale Told on the Seventh of the Heptameron

Heptameron Tale 69

At the castle of Odoz (1) in Bigorre, there dwelt one Charles, equerry to the King and an Italian by birth, who had married a very virtuous and honourable woman. After bearing him many children, she was now grown old, whilst he also was not young. And he lived with her in all peacefulness and affection, for although he would at times speak with his serving-women, his excellent wife took no notice of this, but quietly dismissed them whenever she found that they were becoming too familiar in her house.

One day she hired a discreet and worthy girl, telling her of her husband's temper and her own, and how she was wont to turn away such girls whom she found to be wantons. This maid, wishing to continue in her mistress's service and esteem, resolved to remain a virtuous woman; and although her master often spoke to her, she on her part gave no heed to his words save that she repeated them to her mistress, and they thus both derived much diversion from his folly.

One day the maid was in a back room bolting meal, and wearing her "sarot," a kind of hood which, after the fashion of that country, not only formed a coif but covered the whole of the back and shoulders. Her master, finding her in this trim, came and urged her very pressingly, and, although she would not have done such a thing even to save her life, she pretended to consent, and asked leave to go first and see whether her mistress was engaged in some such manner that they might not be surprised together. To this he agreed; whereupon she begged him to put her hood upon his head and to continue bolting whilst she was away, in order that her mistress might still hear the noise of the bolter. And this he gladly did, in the hope of obtaining what he sought.

The maid, who was by no means inclined to melancholy, ran off to her mistress and said to her—

"Come and see your good husband, whom I have taught to bolt in order to be rid of him."

The wife made all speed to behold this new serving-woman, and when she saw her husband with the hood upon his head and the bolter in his hands, she began to laugh so exceedingly, clapping her hands the while, that she was scarce able to say to him—

"How much dost want a month, wench, for thy labour?"

The husband, on hearing this voice, realised that he had been deceived, and, throwing down both what he was holding and wearing, he ran at the girl, calling her a thousand bad names. Had his wife not set herself in front of the maid, he would have given her wage enough for her quarter; but at last all was settled to the content of the parties concerned, and thenceforward they lived together without quarrelling. (2)

"What say you, ladies, of this wife? Was she not sensible to make sport of her husband's sport?"

"'Twas no sport," said Saffredent, "for the husband who failed in his purpose."

"I believe," said Ennasuite, "that he had more delight in laughing with his wife, than at killing himself at his age with his serving-woman."

"Still, I should be sorely vexed," said Simontault, "to be discovered so bravely coifed."

"I have heard," said Parlamente, "that it was not your wife's fault that she did not once discover you in very much the same attire in spite of all your craft, and that since then she has known no repose."

Heptameron Story 69

"Rest content with what befalls your own house," said Simontault, "without inquiring into what befalls mine. Nevertheless, my wife has no reason to complain of me, and even did I act as you say, she would never have occasion to notice it through any lack of what she might need."

"Virtuous women," said Longarine, "require nothing but the love of their husbands, which alone can satisfy them. Those who seek a brutish satisfaction will never find it where honour enjoins."

"Do you call it brutish," asked Geburon, "if a wife desires that her husband should give her her due?"

"I say," said Longarine, "that a chaste woman, whose heart is filled with true love, is more content to be perfectly loved than to have all the delights that the body can desire."

"I am of your opinion," said Dagoucin, "but my lords here will neither hear it nor confess it. I think if mutual love cannot satisfy a woman, her husband alone will not do so; for unless she live in the love that is honourable for a woman, she must be tempted by the infernal lustfulness of brutes."

"In truth," said Oisille, "you remind me of a lady who was both handsome and well wedded, but who, through not living in that honourable love, became more carnal than swine and more cruel than lions."

"I ask you, madam," said Simontault, "to end the day by telling us her story."

"That I cannot do," said Oisille, "and for two reasons. The first is that it is exceedingly long; and the second, that it does not belong to our own day. It is written indeed by an author worthy of belief; but we are sworn to relate nothing that has been written."

"That is true," said Parlamente; "but I believe I know the story you mean, and it is written in such old language that methinks no one present except ourselves has ever heard of it. It will therefore be looked upon as new."

Upon this the whole company begged her to tell it without fear for its length, seeing that a full hour was yet left before vespers. So, at their request, the Lady Oisille thus began:—

Footnotes:

- The scene of this tale is laid at the castle where Margaret died. Ste. Marthe in his Oraison funèbre, pronounced at Alençon fifteen days after the Queen's death, formally states that she expired at Odos near Tarbes. He is not likely to have been mistaken, so that Brantome's assertion that the Queen died at Audos in Beam may be accepted as incorrect (ante, vol. i. p. lxxxviii.). It is further probable that the above tale was actually written at Odos (ante, vol. i. p. lxxxvi.), but the authenticity of the incidents is very doubtful, as there is an extremely similar story in the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles (No, xvii. Le Conseiller au bluteau), in which the hero of the adventure is a "great clerk and knight who presided over the Court of Accounts in Paris." For subsequent imitations see Malespini's Ducento Novelle (No. xcvii.) and Les Joyeuses Adventures et Nouvelles Recreations (No. xix.)—L. and Ed.

- The Italian Charles, equerry to the King, to whom the leading part is assigned in Queen Margaret's tale, may have been Charles de San Severino, who figures among the equerries with a salary of 200 livres, in the roll of the royal household for 1522. The San Severino family, one of the most prominent of Naples, had attached itself to the French cause at the time of the expedition of Charles VIII., whom several of its members followed to France. In 1522 we find a "Monsieur de Saint-Severin" holding the office of first maître d'hôtel to Francis I., and over a course of several years his son figures among the enfants d'honneur.—B. J. and Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.