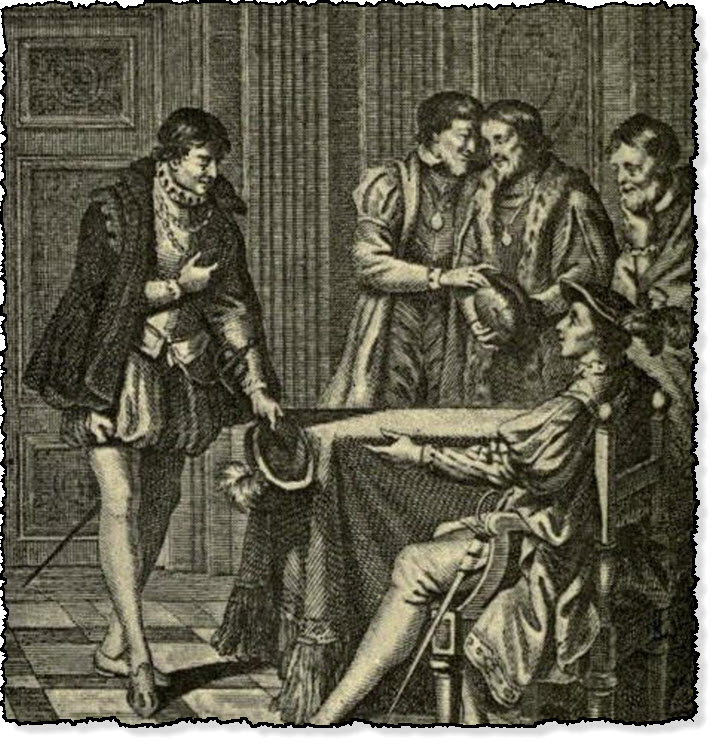

The King Asking The Young Lord to Join his Banquet

The Heptameron - Day 7 - Tale 63 - The King Asking The Young Lord to Join his Banquet

Summary of the Third Tale Told on the Seventh of the Heptameron

The Heptameron - Day 7 - Tale 63

In the city of Paris there lived four girls, of whom two were sisters, and such was their beauty, youth and freshness, that they were run after by all the gallants. A gentleman, however, who at that time held the office of Provost of Paris (2) from the King, seeing that his master was young, of an age to desire such company, so cleverly contrived matters with all four of the damsels that each, thinking herself intended for the King, agreed to what the aforesaid Provost desired. This was that they should all of them be present at a feast to which he invited his master.

He told the latter his plan, which was approved both by the Prince and by two other great personages of the Court, all three agreeing together to share in the spoil.

While they were looking for a fourth comrade, there arrived a handsome and honourable lord who was ten years younger than the others. He was invited to the banquet, but although he accepted with a cheerful countenance, in his heart he had no desire for it. For on the one part he had a wife who was the mother of handsome children, and with whom he lived in great happiness, and in such peacefulness that on no account would he have had her suspect evil of him. And on the other hand he was the lover of one of the handsomest ladies of her time in France, whom he loved and esteemed so greatly that all other women seemed to him ugly beside her.

In his early youth, before he was married, he had found it impossible to gaze upon and associate with other women, however beautiful they might be; for he took more delight in gazing upon his sweetheart, and in perfectly loving her, than in having all that another might have given him.

This lord, then, went to his wife and told her secretly of the enterprise that his master had in hand, saying that he would rather die than do what he had promised. For (he told her) just as there was no living man whom he would not venture to attack in anger, although he would rather die than commit a causeless and wilful murder unless his honour compelled him to it; even so, unless driven by extreme love, such as may serve to blind virtuous men, he would rather die than break his marriage vow to gratify another.

On hearing these words of his, and finding that so much honour dwelt in one so young, his wife loved and esteemed him more than she had ever done before, and inquired how he thought he might best excuse himself, since Princes often frown on those who do not praise what they like.

"I have always heard," he replied, "that a wise man has a journey or a sickness in his sleeve for use in time of need. I have therefore resolved that I will feign a grievous sickness four or five days beforehand, and in this matter your countenance may render me true service."

"Tis a worthy and holy hypocrisy," said his wife, "and I will not fail to serve you with the saddest face I can command; for he who can avoid offending God and angering the Prince is fortunate indeed."

As it was resolved, so was it done, and the King was very sorry to hear from the wife of her husband's sickness. This, however, lasted no long time; for, on account of certain business which arose, the King disregarded his pleasure to attend to his duty, and betook himself away from Paris.

However, one day, remembering their unfinished undertaking, he said to the young lord:—

"We were very foolish to leave so suddenly without seeing the four girls who are declared to be the fairest in my kingdom."

"I am very glad," replied the young lord, "that you failed in the matter, for I was in great fear that, by reason of my sickness, I should be the only one to miss so pleasant an adventure."

By reason of this answer the King never suspected the dissimulation of the young lord, who was thenceforward loved by his wife more dearly than he had ever been before.

Heptameron Story 63

Hereupon Parlamente began to laugh, and could not hold from saying—

"He would have loved his wife better if he had done this for love of her alone. But in any case he is worthy of great praise."

"It seems to me," said Hircan, "that it is no great merit in a man to keep his chastity for love of his wife, inasmuch as there are many reasons which in a manner compel him to do so. In the first place, God commands it; his marriage vow binds him to it, and, further, surfeited nature is not liable to temptation or desire as necessity is. But when the unfettered love that a man bears towards a mistress of whom he has no delight, and no other happiness save that of seeing her and speaking with her, and from whom he often receives harsh replies—when this love is so loyal and steadfast that nothing can ever make it change, I say that such chastity is not simply praiseworthy but miraculous."

"'Tis no miracle in my opinion," said Oisille, "for when the heart is plighted, nothing is impossible to the body."

"True," said Hircan; "to bodies which have become those of angels."

"I do not speak only of those," said Oisille, "who by the grace of God are wholly transformed into Himself, but of the grosser spirits that we see here below among men. And, if you give heed, you will find that those who have set their hearts and affections upon seeking after the perfection of the sciences, have forgotten not only the lust of the flesh, but even the most needful matters, such as food and drink; for so long as the soul is stirred within the body, so long does the flesh continue as though insensible. Thence comes it that those who love handsome, honourable and virtuous women have such happiness of spirit in seeing them and speaking with them, that the flesh is lulled in all its desires. Those who cannot feel this happiness are the carnally-minded, who, wrapped in their exceeding fatness, cannot tell whether they have a soul or not. But, when the body is in subjection to the spirit, it is as though heedless of the failings of the flesh, and the beliefs of such persons may render them insensible of the same. I knew a gentleman who, to show that he loved his mistress more dearly than did any other man, proved it to all his comrades by holding his bare fingers in the flame of a candle. And then, with his eyes fixed upon his mistress, he remained firm until he had burned himself to the bone, and yet said that he had felt no hurt."

"Methinks," said Geburon, "that the devil whose martyr he was ought to have made a St. Lawrence of him; for there are few whose love-flame is hot enough to keep them from fearing that of the smallest taper. But if a lady had suffered me to endure so much hurt for her sake, I should either have sought a rich reward or else have taken my love away from her."

"So," said Parlamente, "you would have your hour after the lady had had hers? That was what was done by a gentleman of the neighbourhood of Valencia in Spain, whose story was told to me by a captain, a right worthy man."

"I pray you, madam," said Dagoucin, "take my place and tell it us, for I am sure that it must be a good one."

"This story, ladies," said Parlamente, "will teach you both to think twice when you are inclined to give a refusal and to lay aside the thought that the present will always continue; and so, knowing that it is subject to mutation, you will have a care for the time to come."

Footnotes:

- This story, omitted by Boaistuau, was included in Gruget's edition of the Heptameron.—L.

- This is John de la Barre, already alluded to in Tale I. The Journal d'un Bourgeois de Paris tells us that he was born in Paris of poor parents, and became a favourite of Francis I., who appointed him Bailiff of the capital, without requiring him to pay any of the dues attaching to the office. From the roll of the royal household for 1522, we also find that he was then a gentleman of the bed chamber with 1200 livres salary, master of the wardrobe (a post worth 200 livres) and governor of the pages, for the board and clothing of whom he received 5000 livres annually. In 1526 he became Provost as well as Bailiff of Paris, the two offices then being amalgamated. He was further created Count of Etampes, and acquired the lordship of Veretz, best remembered by its associations with the murder of Paul Louis Courier. La Barre fought at Pavia, was taken prisoner with the King, and remained his constant companion during his captivity. Several letters of his, dating from this period and of great historical interest, are still extant; some of them have been published by Champollion-Figeac (Captivité de François Ier) and Génin (Lettres de Marguerite, &c). Under date 1533 (o. s.) the "Bourgeois de Paris" writes in his Journal: "At the beginning of March there died in Paris, at the house of Monsieur Poncher, Monsieur le Prévost de Paris, named de La Barre.... The King was then in Paris, at his chateau of the Louvre, and there was great pomp at the obsequies; and he was borne to his lordship of Veretz, near Tours, that he might be buried there." Numerous particulars concerning La Barre will also be found in M. de Laborde's Comptes des Bâtiments du Roi au XVIeme Siècle.— L. and Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.