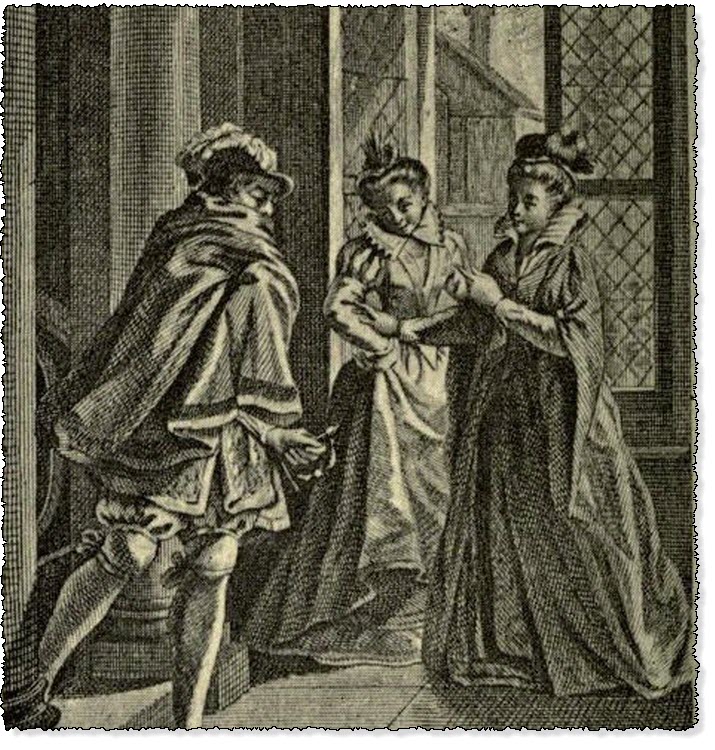

The Gentleman Mocked by The Ladies when Returning from The False Tryst

The Heptameron - Day 6 - Tale 58 - The Gentleman Mocked by The Ladies when Returning from The False Tryst

Summary of the Eighth Tale Told on the Sixth of the Heptameron

Tale 58 of the Heptameron

At the Court of King Francis the First there was a lady (1) of excellent wit, who, by her grace, virtue and pleasantness of speech, had won the hearts of several lovers. With these she right well knew how to pass the time, but without hurt to her honour, conversing with them in such pleasant fashion that they knew not what to think, for those who were the most confident were reduced to despair, whilst those that despaired the most became hopeful. Nevertheless, while fooling most of them, she could not help greatly loving one whom she called her cousin, a name which furnished a pretext for closer fellowship.

However, as there is nothing in this world of firm continuance, their friendship often turned to anger and then was renewed in stronger sort than ever, so that the whole Court could not but be aware of it.

One day the lady, both to let it be seen that she was wholly void of passion, and to vex him, for love of whom she had endured much annoyance, showed him a fairer countenance than ever she had done before. Thereupon the gentleman, who lacked boldness neither in love nor in war, began hotly to press the suit that he many a time previously had addressed to her.

She, pretending to be wholly vanquished by pity, promised to grant his request, and told him that she would with this intent go into her room, which was on a garret floor, where she knew there was nobody. And as soon as he should see that she was gone he was to follow her without fail, for he would find her ready to give proof of the good-will that she bore him.

The gentleman, believing what she said, was exceedingly well pleased, and began to amuse himself with the other ladies until he should see her gone, and might quickly follow her. But she, who lacked naught of woman's craftiness, betook herself to my Lady Margaret, daughter of the King, and to the Duchess of Montpensier, (2) to whom she said—

"I will if you are willing, show you the fairest diversion you have ever seen."

They, being by no means enamoured of melancholy, begged that she would tell them what it was.

"You know such a one," she replied, "as worthy a gentleman as lives, and as bold. You are aware how many ill turns he has done me, and that, just when I loved him most, he fell in love with others, and so caused me more grief than I have ever suffered to be seen. Well, God has now afforded me the means of taking revenge upon him.

"I am forthwith going to my own room, which is overhead, and immediately afterwards, if it pleases you to keep watch, you will see him follow me. When he has passed the galleries, and is about to go up the stairs, I pray you come both to the window and help me to cry 'Thief!' You will then see his rage, which, I am sure, will not become him badly, and, even if he does not revile me aloud, I am sure he will none the less do so in his heart."

This plan was not agreed to without laughter, for there was no gentleman that tormented the ladies more than he did, whilst he was so greatly liked and esteemed by all, that for nothing in the world would any one have run the risk of his raillery.

It seemed, moreover, to the two Princesses that they would themselves share in the glory which the other lady looked to win over this gentleman.

Accordingly, as soon as they saw the deviser of the plot go out, they set themselves to observe the gentleman's demeanour. But little time went by before he shifted his quarters, and, as soon as he had passed the door, the ladies went out into the gallery, in order that they might not lose sight of him.

Suspecting nothing, he wrapped his cloak about his neck, so as to hide his face, and went down the stairway to the court, but, seeing some one whom he did not desire to have for witness, he came back by another way, and then went down into the court a second time. The ladies saw everything without being perceived by him, and when he reached the stairway, by which he thought he might safely reach his sweetheart's chamber, they went to the window, whence they immediately perceived the other lady, who began crying out 'Thief!' at the top of her voice; whereupon the two ladies below answered her so loudly that their voices were heard all over the castle.

I leave you to imagine with what vexation the gentleman fled to his lodgings. He was not so well muffled as not to be known by those who were in the mystery, and they often twitted him with it, as did even the lady who had done him this ill turn, saying that she had been well revenged upon him.

Heptameron Story 58

It happened, however, that he was so ready with his replies and evasions as to make them believe that he had quite suspected the plan, and had only consented to visit the lady in order to furnish them with some diversion, for, said he, he would not have taken so much trouble for her sake, seeing that his love for her had long since flown. The ladies would not admit the truth of this, so that the point is still in doubt; nevertheless, it is probable that he believed the lady. And since he was so wary and so bold that few men of his age and time could match and none could surpass him (as has been proved by his very brave and knightly death), (3) you must, it seems to me, confess that men of honour love in such wise as to be often duped, by placing too much trust in the truthfulness of the ladies.

"In good faith," said Ennasuite, "I commend this lady for the trick she played; for when a man is loved by a lady and forsakes her for another, her vengeance cannot be too severe."

"Yes," said Parlamente, "if she is loved by him; but there are some who love men without being certain that they are loved in return, and when they find that their sweethearts love elsewhere, they call them fickle. It therefore happens that discreet women are never deceived by such talk, for they give no heed or belief even to those people who speak truly, lest they should prove to be liars, seeing that the true and the false speak but one tongue."

"If all women were of your opinion," said Simon-tault, "the gentlemen might pack up their prayers at once; but, for all that you and those like you may say, we shall never believe that women are as unbelieving as they are fair. And in this wise we shall live as content as you would fain render us uneasy by your maxims."

"Truly," said Longarine, "knowing as I well do who the lady is that played that fine trick upon the gentleman, it is impossible for me not to believe in any craftiness on her part. Since she did not spare her husband, 'twere fitting she should not spare her lover."

"Her husband, say you?" said Simontault. "You know, then, more than I do, and so, since you wish it, I give you my place that you may tell us your opinion of the matter."

"And since you wish it," said Longarine, "I will do so."

Footnotes:

- M. de Lincy surmises that Margaret is referring to herself both here and in the following tale, which concerns the same lady. His only reason for the supposition, however, is that the lady's views on certain love matters are akin to those which the Queen herself professed.—Ed.

The former is Margaret of France, Duchess of Savoy and Berry. Born in June 1523, she died in September 1574.— Queen Margaret was her godmother. When only three years old, she was promised in marriage to Louis of Savoy, eldest son of Duke Charles III., and he dying, she espoused his younger brother, Emmanuel Philibert, in July 1549. Graceful and pretty as a child (see ante, vol. i. p. xlviii.), she became, thanks to the instruction of the famous Michael de l' Hôpital, one of the most accomplished women of her time, and Brantôme devotes an article to her in his Dames Illustres (Lalanne, v. viii. pp. 328-37). See also Hilarion de Coste's Éloges et Vies des Reines, Princesses, &c., Paris, 1647, vol. ii. p. 278.

The Duchess of Montpensier, also referred to above, is Jacqueline de Longwick (now Longwy), Countess of Bar-sur- Seine, daughter of J. Ch. de Longwick, Lord of Givry, and of Jane, bâtarde of Angoulême. In 1538 Jacqueline was married to Louis II. de Bourbon, Duke of Montpensier. She gained great influence at the French Court, both under Francis I. and afterwards, and De Thou says of her that she was possessed of great wit and wisdom, far superior to the century in which she lived. She died in August 1561, and was the mother of Francis I., Duke of Montpensier, sometimes called the Dauphin of Auvergne, who fought at Jarnac, Moncontour, Arques, and Ivry, against Henry of Navarre.—L., B. J. and Ed.

- This naturally brings Bonnivet to mind, though of course the gay, rash admiral was not the only Frenchman of the time who spent his life in making love and waging war.—Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.