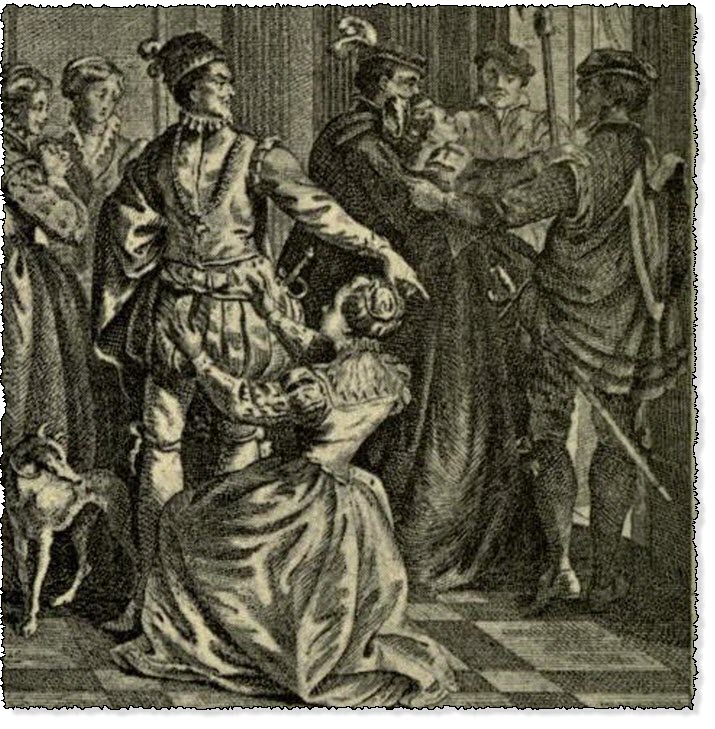

the Duke of Urbino Sending The Maiden to Prison for Carrying Messages

The Heptameron - Day 6 - Tale 51 - the Duke of Urbino Sending The Maiden to Prison for Carrying Messages

Summary of the First Tale Told on the Sixth Day of the Heptameron

DAY 6 - TALE 51 of the Heptameron

The Duke of Urbino, called the Prefect, (1) the same that married the sister of the first Duke of Mantua, had a son of between eighteen and twenty years of age, who was in love with a girl of an excellent and honourable house, sister to the Abbot of Farse. (2) And since, according to the custom of the country, he was not free to converse with her as he wished, he obtained the aid of a gentleman in his service, who was in love with a very beautiful and virtuous young damsel in the service of his mother. By means of this damsel he informed his sweetheart of the deep affection that he bore her; and the poor girl, thinking no harm, took pleasure in doing him service, believing his purpose to be so good and virtuous that she might honourably be the carrier of his intentions. But the Duke, who had more regard for the profit of his house than for any virtuous affection, was in such great fear lest these dealings should lead his son (3) into marriage, that he caused a strict watch to be kept; whereupon he was informed that the poor damsel had been concerned in carrying some letters from his son to the lady he loved. On hearing this he was in great wrath, and resolved to take the matter in hand.

He could not, however, conceal his anger so well that the maiden was not advised of it, and knowing his wickedness, which was in her eyes as great as his conscience was small, she felt a wondrous dread. Going therefore to the Duchess, she craved leave to retire somewhere out of the Duke's sight until his passion should be past; but her mistress replied that, before giving her leave to do so, she would try to find out her husband's will in the matter.

Very soon, however, the Duchess heard the Duke's evil words concerning the affair, and, knowing his temper, she not only gave the maiden leave, but advised her to retire into a convent until the storm was over. This she did as secretly as she could, yet not so stealthily but that the Duke was advised of it. Thereupon, with pretended cheerfulness of countenance, he asked his wife where the maiden was, and she, believing him to be well aware of the truth, confessed it to him. He feigned to be vexed thereat, saying that the girl had no need to behave in that fashion, and that for his part he desired her no harm. And he requested his wife to cause her to come back again, since it was by no means well to have such matters noised abroad.

The Duchess replied that, if the poor girl was so unfortunate as to have lost his favour, it were better for a time that she should not come into his presence; however, he would not hearken to her reasonings, but commanded her to bid the maiden return.

The Duchess failed not to make the Duke's will known to the maiden; but the latter, who could not but feel afraid, entreated her mistress that she might not be compelled to run this risk, saying that she knew the Duke was not so ready to forgive her as he feigned to be. Nevertheless, the Duchess assured her that she should take no hurt, and pledged her own life and honour for her safety.

Heptameron Story 51

The girl, who well knew that her mistress loved her, and would not lightly deceive her, trusted in her promise, believing that the Duke would never break a pledge when his wife's honour was its warranty. And accordingly she returned to the Duchess.

As soon as the Duke knew this, he failed not to repair to his wife's apartment. There, as soon as he saw the maiden, he said to his wife, "So such-a-one has returned," and turning to his gentlemen, he commanded them to arrest her and lead her to prison.

At this the poor Duchess, who by the pledging of her word had drawn the maiden from her refuge, was in such despair that, falling upon her knees before her husband, she prayed that for love of herself and of his house he would not do so foul a deed, seeing that it was in obedience to himself that she had drawn the maiden from her place of safety.

But no prayer that she could utter availed to soften his hard heart, or to overcome his stern resolve to be avenged. Without making any reply, he withdrew as speedily as possible, and, foregoing all manner of trial, and forgetting God and the honour of his house, he cruelly caused the hapless maiden to be hanged.

I cannot undertake to recount to you the grief of the Duchess; it was such as beseemed a lady of honour and a tender heart on beholding one, whom she would fain have saved, perish through trust in her own plighted faith. Still less is it possible to describe the deep affliction of the unhappy gentleman, the maiden's lover, who failed not to do all that in him lay to save his sweetheart's life, offering to give his own for hers; but no feeling of pity moved the heart of this Duke, whose only happiness was that of avenging himself on those whom he hated. (4)

Thus, in spite of every law of honour, was the innocent maiden put to death by this cruel Duke, to the exceeding sorrow of all that knew her.

"See, ladies, what are the effects of wickedness when this is combined with power."

"I had indeed heard," said Longarine, "that the Italians were prone to three especial vices; but I should not have thought that vengeance and cruelty would have gone so far as to deal a cruel death for so slight a cause."

"Longarine," said Saffredent, laughing, "you have told us one of the three vices, but we must also know the other two."

"If you did not know them," she replied, "I would inform you, but I am sure that you know them all."

"From your words," said Saffredent, "it seems that you deem me very vicious."

"Not so," said Longarine, "but you so well know the ugliness of vice that, better than any other, you are able to avoid it."

"Do not be amazed," said Simontault, "at this act of cruelty. Those who have passed through Italy have seen such incredible instances, that this one is in comparison but a trifling peccadillo."

"Ay, truly," said Geburon. "When Rivolta was taken by the French, (5) there was an Italian captain who was esteemed a knightly comrade, but on seeing the dead body of a man who was only his enemy in that being a Guelph he was opposed to the Ghibellines, he tore out his heart, broiled it on the coals and devoured it. And when some asked him how he liked it, he replied that he had never eaten so savoury or dainty a morsel. Not content with this fine deed, he killed the dead man's wife, and tearing out the fruit of her womb, dashed it against a wall. Then he filled the bodies both of husband and wife with oats and made his horses eat from them. Think you that such a man as that would not surely have put to death a girl whom he suspected of offending him?"

"It must be acknowledged," said Ennasuite, "that this Duke of Urbino was more afraid that his son might make a poor marriage than desirous of giving him a wife to his liking."

"I think you can have no doubt," replied Simon-tault, "that it is the Italian nature to love unnaturally that which has been created only for nature's service."

"Worse than that," said Hircan, "they make a god of things that are contrary to nature."

"And there," said Longarine, "you have another one of the sins that I meant; for we know that to love money, excepting so far as it be necessary, is idolatry."

Parlamente then said that St. Paul had not forgotten the vices of the Italians, and of all those who believe that they exceed and surpass others in honour, prudence and human reason, and who trust so strongly to this last as to withhold from God the glory that is His due. Wherefore the Almighty, jealous of His honour, renders' those who believe themselves possessed of more understanding than other men, more insensate even than wild the beasts, causing them to show by their unnatural deeds that their sense is reprobate.

Longarine here interrupted Parlamente to say that this was indeed the third sin to which the Italians were prone.

"By my faith," said Nomerfide, "this discourse is very pleasing to me, for, since those that possess the best trained and acutest understandings are punished by being made more witless even than wild beasts, it must follow that such as are humble, and low, and of little reach, like myself, are filled with the wisdom of angels."

"I protest to you," said Oisille, "that I am not far from your opinion, for none is more ignorant than he who thinks he knows."

"I have never seen a mocker," said Geburon, "that was not mocked, a deceiver that was not deceived, or a boaster that was not humbled."

"You remind me," said Simontault, "of a deceit which, had it been of a seemly sort, I would willingly have related."

"Well," said Oisille, "since we are here to utter truth, I give you my vote that you may tell it to us whatsoever its nature may be."

"Since you give place to me," said Simontault, "I will tell it you."

Footnotes:

- This is Francesco Maria I., della Rovere, nephew to Pope Julius II., by whom he was created Prefect of Rome. Brought up at the French Court, he became one of the great captains of the period, especially distinguishing himself in the command of the Venetian forces during the earlier part of his career. He married Leonora Ypolita Gonzaga, daughter of Francesco II., fourth Marquis of Mantua, respecting whom see ante, vol. iii., notes to Tale XIX. It was Leonora rather than her husband who imparted lustre to the Court of Urbino at this period by encouraging arts and letters. Among those who flourished there were Raffaelle and Baldassare Castiglione. Francesco Maria, born in March 1491, died in 1538 from the effects—so it is asserted by several contemporary writers—of a poisonous lotion which a Mantuan barber had dropped into his ear. His wife, who bore him two sons (see post, note 3), died at the age of 72, in 1570.—L. and Ed.

- The French words are Abbé de Farse. Farse would appear to be a locality, as abbots were then usually designated by the names of their monasteries; still it may be intended for the Abbot's surname, and some commentators, adopting this view, have suggested that the proper reading would be Farnese.—Ed.

- The Duke's two sons were Federigo, born in March 1511, and Guidobaldo, born in April 1514. The former according to all authorities died when "young," and probably long before reaching man's estate. Dennistoun, in his searching Memoirs of the Dukes of Urbino (London, 1851), clearly shows that for many years prior to Francesco Maria's death his second son Guidobaldo was the only child remaining to him. Already in 1534, when but twenty years old, Guidobaldo was regarded as his father's sole heir and successor. In that year Francesco Maria forced the young man to marry Giulia Varana, a child of eleven, in order that he might lay claim to her father's state of Camerino and annex it to the duchy. There is no record of Guidobaldo having ever engaged in any such intrigue as related by Queen Margaret in the above tale, still it must be to him that she refers, everything pointing to the conclusion that his brother Federigo died in childhood. Guidobaldo became Duke of Urbino on his father's death.—Ed.

- That Francesco-Maria was a man of a hasty, violent temperament is certain. Much that Guicciardini relates of him was doubtless penned in a spirit of resentment, for during the time the historian lived at Urbino the Duke repeatedly struck him, and on one occasion felled him to the ground, with the sneering remark, "Your business is to confer with pedants." On the other hand, however, there is independent documentary evidence in existence—notably among the Urbino MSS. in the Vatican library—which shows that Francesco-Maria in no wise recoiled from shedding blood. He was yet in his teens when it was reported to him that his sister—the widow of Venanzio of Camerino, killed by Caesar Borgia—had secretly married a certain Giovanni Andrea of Verona and borne him a son. Watching his opportunity, Francesco-Maria set upon the unfortunate Andrea one day in the ducal chamber and then and there killed him, though not without resistance, for Andrea only succumbed after receiving four-and-twenty stabs with his murderer's poignard (Urbino MSS. Vat. No. 904). A few years later, in 1511, Francesco-Maria assassinated the Papal Legate Alidosio, Cardinal Archbishop of Pavia, whom he encountered in the environs of Bologna riding his mule and followed by a hundred light horse. Nevertheless Urbino, with only a small retinue, galloped up to him, plunged a dagger into his stomach and fled before the soldiery could intervene. From these examples it will be seen that, although history has preserved no record of the affair related by Queen Margaret, her narrative may well be a true one.—Ed.

- Rivolta or Rivoli was captured by the French under Louis XII. in 1509. An instance of savagery identical in character with that mentioned by "Geburon" had already occurred at the time of Charles VIII.'s expedition to Naples, when the culprit, a young Italian of good birth, was seized and publicly executed.—Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.