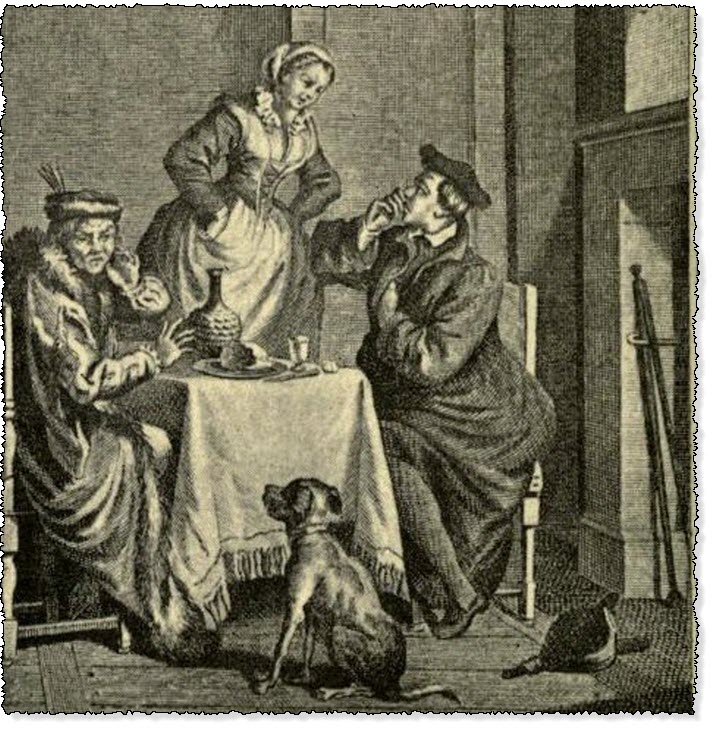

the Gentleman and his Friend Annoyed by The Smell of Sugar

The Heptameron - Day 6 - Tale 52 - the Gentleman and his Friend Annoyed by The Smell of Sugar

Summary of the Second Tale Told on the Sixth Day of the Heptameron

Tale 52 Day of the Heptameron

Near the town of Alençon there lived a gentleman called the Lord of La Tireliere, who one morning came from his house to the town afoot, both because the distance was not great and because it was freezing hard. (1) When he had done his business, he sought out a crony of his, an advocate named Anthony Bacheré, and, after speaking with him of his affairs, he told him that he should much like to meet with a good breakfast, but at somebody else's expense. While thus discussing, they sat themselves down in front of an apothecary's shop, where there was a varlet who listened to them, and who forthwith resolved to give them their breakfast.

He went out from his shop into a street whither all repaired on needful occasions, (2) and there found a large lump of ordure standing on end, and so well frozen that it looked like a small loaf of fine sugar. Forthwith he wrapped it in handsome white paper, in the manner he was wont to use for the attraction of customers, and hid it in his sleeve.

Afterwards he came and passed in front of the gentleman and the advocate, and, letting the sugar-loaf (3) fall near them, as if by mischance, went into a house whither he had pretended to be carrying it.

The Lord of La Tirelière (4) hastened back with all speed to pick up what he thought to be a sugar-loaf, and just as he had done so the apothecary's man also came back looking and asking for his sugar everywhere.

The gentleman, thinking that he had cleverly tricked him, then went in haste to a tavern with his crony, to whom he said—

"Our breakfast has been paid for at the cost of that varlet."

When he was come to the tavern he called for good bread, good wine and good meat, for he thought that he had wherewith to pay. But whilst he was eating, as he began to grow warm, his sugar-loaf in its turn began to thaw and melt, and filled the whole room with the smell peculiar to it, whereupon he, who carried it in his bosom, grew wroth with the waiting-woman, and said to her—

"You are the filthiest folks that ever I knew in this town, for either you or your children have strewn all this room with filth."

"By St. Peter!" replied the woman, "there is no filth here unless you have brought it in yourselves."

Thereupon they rose, by reason of the great stench that they smelt, and went up to the fire, where the gentleman drew out of his bosom a handkerchief all dyed with the melted sugar, and on opening his robe, lined with fox-skin, found it to be quite spoiled.

And all that he was able to say to his crony was this—

"The rogue whom we thought to deceive has deceived us instead."

Then they paid their reckoning and went away as vexed as they had been merry on their arrival, when they fancied they had tricked the apothecary's varlet. (5)

"Often, ladies, do we see the like befall those who delight in using such cunning. If the gentleman had not sought to eat at another's expense, he would not have drunk so vile a beverage at his own. It is true, ladies, that my story is not a very clean one, but you gave me license to speak the truth, and I have done so in order to show you that no one is sorry when a deceiver is deceived."

Heptameron Story 52

"It is commonly said," replied Hircan, "that words have no stink, yet those for whom they are intended do not easily escape smelling them."

"It is true," said Oisille, "that such words do not stink, but there are others which are spoken of as nasty, and which are of such evil odour that they disgust the soul even more than the body is disgusted when it smells such a sugar-loaf as you described in the tale."

"I pray you," said Hircan, "tell me what words you know of so foul as to sicken both the heart and soul of a virtuous woman."

"It would indeed be seemly," replied Oisille, "that I should tell you words which I counsel no woman to utter."

"By that," said Saffredent, "I quite understand what those terms are. They are such as women desirous of being held discreet do not commonly employ. But I would ask all the ladies present why, when they dare not utter them, they are so ready to laugh at them when they are used in their presence."

Then said Parlamente—

"We do not laugh because we hear such pretty expressions, though it is indeed true that every one is disposed to laugh on seeing anybody stumble or on hearing any one utter an unfitting word, as often happens. The tongue will trip and cause one word to be used for another, even by the discreetest and most excellent speakers. But when you men talk viciously, not from ignorance, but by reason of your own wickedness, I know of no virtuous woman who does not feel a loathing for such speakers, and who would not merely refuse to hearken to them, but even to remain in their company."

"That is very true," responded Geburon. "I have frequently seen women make the sign of the cross on hearing certain words spoken, and cease not in doing so after these words had been uttered a second time."

"But how many times," said Simontault, "have they put on their masks (6) in order to laugh as freely as they pretended to be angry?"

"Yet it were better to do this," said Parlamente, "than to let it be seen that the talk pleased them."

"Then," said Dagoucin, "you praise a lady's hypocrisy no less than her virtue?"

"Virtue would be far better," said Longarine, "but, when it is lacking, recourse must be had to hypocrisy, just as we use our slippers (7) to disguise our littleness. And it is no small matter to be able to conceal our imperfections."

"By my word," said Hircan, "it were better sometimes to show some slight imperfection than to cover it so closely with the cloak of virtue."

"It is true," said Ennasuitc, "that a borrowed garment brings the borrower as much dishonour when he is constrained to return it as it brought him honour whilst it was being worn, and there is a lady now living who, by being too eager to conceal a small error, fell into a greater."

"I think," said Hircan, "that I know whom you mean; in any case, however, do not pronounce her name."

"Ho! ho!" said Geburon [to Ennasuite], "I give you my vote on condition that when you have related the story you will tell us the names. We will swear never to mention them."

"I promise it," said Knnasuite, "for there is nothing that may not be told in all honour."

Footnotes:

- The phraseology of this story varies considerably in the different MSS. of the Heptameron. In No. 1520, for instance, the tale begins as follows: "In the town of Alençon, in the time of the last Duke Charles, there was an advocate, a merry companion, fond of breakfasting o' mornings. One day, whilst he sat at his door, he saw pass a gentleman called the Lord of La Tilleriere, who, by reason of the extreme cold, had come on foot from his house to the town in order to attend to certain business there, and in doing so had not forgotten to put on his great robe, lined with fox-skin. And when he saw the advocate, who was much such a man as himself, he told him that he had completed his business, and had nothing further to do, except it were to find a good breakfast. The advocate made answer that they could find breakfasts enough and to spare, provided they had some one to defray the cost, and, taking the other under the arm, he said to him, 'Come, gossip, we may perhaps find some fool who will pay the reckoning for us both.' Now behind them was an apothecary's man, an artful and inventive fellow, whom this advocate was always plaguing," &c.—L.

- In olden time, as shown in the Mémoires de l'Académie de Troyes, there were in most French towns streets specially set aside for the purpose referred to. At Alençon, in Queen Margaret's time, there was a street called the Rue des Fumiers, as appears from a report dated March 8, 1564 (Archives of the Orne, Series A). Probably it is to this street that she alludes. (Communicated by M. L. Duval, archivist of the department of the Orne).—M.

- M. Duval, archivist of the Orne, states that La Tirelière, which is situated near St. Germain-du-Corbois, within three miles of Alençon, is an old gentilhommière or manor-house, surrounded by a moat. It was originally a simple vavassonrie held in fief from the Counts and Dukes of Alençon by the Pantolf and Crouches families, and in the seventeenth century was merged into the marquisate of L'Isle.—M.

- Sugar was at this period sold by apothecaries, and was a rare and costly luxury. There were loaves of various sizes, but none so large as those of the present time.—M.

- In MS. 1520, this tale ends in the following manner:— "They were no sooner in the street than they perceived the apothecary's man going about and making inquiry of every one whether they had not seen a loaf of sugar wrapped in paper. They [the advocate and his companion] sought to avoid him, but he called aloud to the advocate, 'If you have my loaf of sugar, sir, I beg that you will give it back to me, for 'tis a double sin to rob a poor servant.' His shouts brought to the spot many people curious to witness the dispute, and the true circumstances of the case were so well proven, that the apothecary's man was as glad to have been robbed as the others were vexed at having committed such a nasty theft. However, they comforted themselves with the hope that they might some day give him tit for tat."—Ed.

- Tourets-de-nez. See ante, vol. iii. p. 27, note 5.—Ed.

- High-heeled slippers or mules were then worn.—B. J.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.