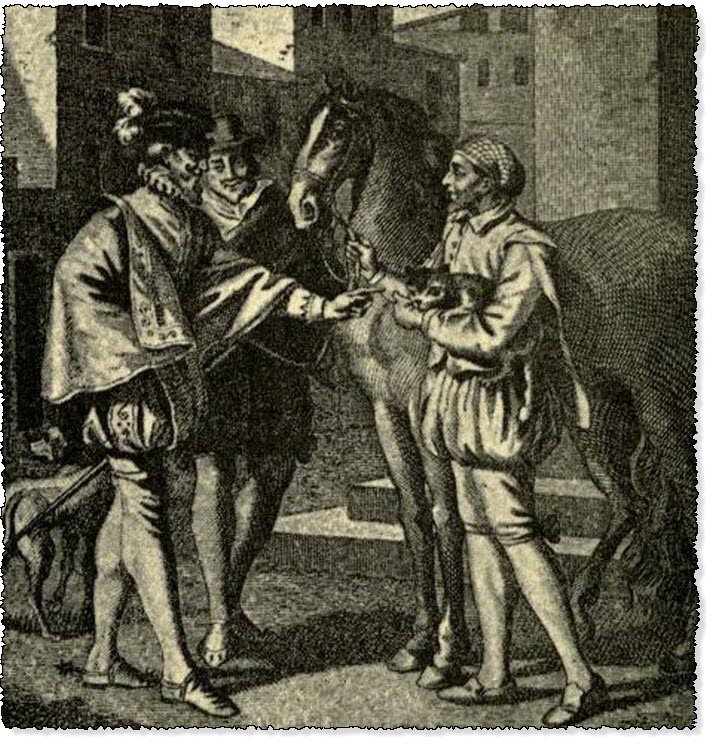

the Servant Selling The Horse With The Cat

The Heptameron - Day 6 - Tale 55 - the Servant Selling The Horse With The Cat

Summary of the Fifth Tale Told on the Sixth of the Heptameron

Tale 55 of the Heptameron

In the town of Safagossa there lived a rich merchant, who, finding his death draw nigh, and himself no longer able to retain possession of his goods—-which he had perchance gathered together by evil means—thought that if he made a little present to God, he might thus after his death make part atonement for his sins, just as though God sold His pardon for money. Accordingly, when he had settled matters in respect of his house, he declared it to be his desire that a fine Spanish horse which he possessed should be sold for as much as it would bring, and the money obtained for it be distributed among the poor. And he begged his wife that she would in no wise fail to sell the horse as soon as he was dead, and distribute the money in the manner he had commanded.

When the burial was over and the first tears were shed, the wife, who was no more of a fool than Spanish women are used to be, went to the servant who with herself had heard his master declare his desire, and said to him—

"Methinks I have lost enough in the person of a husband I loved so dearly, without afterwards losing his possessions. Yet would I not disobey his word, but rather better his intention; for the poor man, led astray by the greed of the priests, thought to make a great sacrifice to God in bestowing after his death a sum of money, not a crown of which, as you well know, he would have given in his lifetime to relieve even the sorest need. I have therefore bethought me that we will do what he commanded at his death, and in still better fashion than he himself would have done if had he lived a fortnight longer. But no living person must know aught of the matter."

When she had received the servant's promise to keep it secret, she said to him—

"You will go and sell the horse, and when you are asked, 'How much?' you will reply, 'A ducat.' I have, however, a very fine cat which I also wish to dispose of, and you will sell it with the horse for ninety-nine ducats, so that cat and horse together will bring in the hundred ducats for which my husband wished to sell the horse alone."

The servant readily fulfilled his mistress's command. While he was walking the horse about the market-place, and holding the cat in his arms, a gentleman, who had seen the horse before, and was desirous of possessing it, asked the servant what price he sought.

"A ducat," replied the man.

"I pray you," said the gentleman, "do not mock me."

"I assure you, sir," said the servant, "that it will cost you only a ducat. It is true that the cat must be bought at the same time, and for the cat I must have nine and ninety ducats."

Heptameron Story 55

Forthwith, the gentleman, thinking the bargain a reasonable one, paid him one ducat for the horse, and the remainder as was desired of him, and took his goods away.

The servant, on his part, went off with the money, with which his mistress was right well pleased, and she failed not to give the ducat that the horse had brought to the poor Mendicants, (3) as her husband had commanded, and the remainder she kept for the needs of herself and her children. (3)

"What think you? Was she not far more prudent than her husband, and did she not think less of her conscience than of the advantage of her household?"

"I think," said Parlamente, "that she did love her husband; but, seeing that most men wander in their wits when at the point of death, and knowing his intentions, she tried to interpret them to her children's advantage. And therein I hold her to have been very prudent."

"What!" said Geburon. "Do you not hold it a great wrong not to carry out the last wishes of departed friends?"

"Assuredly I do," said Parlamente; "that is to say if the testator be in his right mind, and not raving."

"Do you call it raving to give one's goods to the Church and the poor Mendicants?"

"I do not call it raving," said Parlamente, "if a man distribute what God has given into his hands among the poor; but to make alms of another person's goods is, in my opinion, no great wisdom. You will commonly see the greatest usurers build the handsomest and most magnificent chapels imaginable, thinking they may appease God with ten thousand ducats' worth of building for a hundred thousand ducats' worth of robbery, just as though God did not know how to count."

"In sooth," said Oisille, "I have many a time wondered how they can think to appease God for things which He Himself rebuked when He was on earth, such as great buildings, gildings, pictures and paint. If they really understood the passage in which God says to us that the only offering He requires from us is a contrite and humble heart, (4) and the other in which St. Paul says we are the temples of God wherein He desires to dwell, (5) they would be at pains to adorn their consciences while yet alive, and would not wait for the hour when man can do nothing more, whether good or evil, nor (what is worse) charge those who remain on earth to give their alms to folk upon whom, during their lifetime, they did not deign to look. But He who knows the heart cannot be deceived, and will judge them not according to their works, but according to their faith and charity towards Himself."

"Why is it, then," said Geburon, "that these Grey Friars and Mendicants talk to us at our death of nothing but bestowing great benefits upon their monasteries, assuring us that they will put us into Paradise whether we will or not?"

"How now, Geburon?" said Hircan. "Have you forgotten the wickedness you related to us of the Grey Friars, that you ask how such folk find it possible to lie? I declare to you that I do not think that there can be greater lies than theirs. Those, indeed, who speak on behalf of the whole community are not to be blamed, but there are some among them who forget their vows of poverty in order to satisfy their own greed."

"Methinks, Hircan," said Nomerfide, "you must know some such tale, and if it be worthy of this company, I pray you tell it us."

"I will," said Hircan, "although it irks me to speak of such folk. Methinks they are of the number of those of whom Virgil says to Dante, 'Pass on and heed them not.' (6) Still, to show you that they have not laid aside their passions with their worldly garments, I will tell you of something that once came to pass."

Footnotes:

- Whether the incidents here related be true or not, it is

probable that this was a story told to Queen Margaret at the

time of her journey to Spain in 1525. It will have been

observed (ante, pp. 36 and 42) that both the previous tale

and this one are introduced into the Heptameron in a semi-

apologetic fashion, as though the Queen had not originally

intended that her work should include such short, slight

anecdotes. However, already at this stage—the fifty-fifth

only of the hundred tales which she proposed writing—she

probably found fewer materials at her disposal than she had

anticipated, and harked back to incidents of her earlier

years, which she had at first thought too trifling to

record. Still, slight as this story may be, it is not

without point. The example set by the wife of the Saragossa

merchant has been followed in modern times in more ways than

one.—Ed.

- The allusion is not to the ordinary beggars who then, as now, swarmed in Spain, but to the Mendicant friars.—Ed.

- In Boaistuau's and Gruget's editions of the Heptameron the dialogue following this tale is replaced by matter of their own invention. They did not dare to reproduce Queen Margaret's bold opinions respecting the clergy, the monastic orders, &c., at a time when scores of people, including even Counsellors of Parliament, were being burnt at the stake for heresy.—L. and Ed.

- "The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit: a broken and a contrite heart, O God, thou will not despise."—Psalm li. 17.—Ed.

- "For ye are the temple of the living God; as God hath said, I will dwell in them and walk in them," &c.—2 Corinthians vi. 16.—Ed.

- Non ragioniam di lor, ma guarda e passa (Dante's Purgatorio, iii. 51). The allusion is to the souls of those who led useless and idle lives on earth, supporting neither the Divinity by the observance of virtue, nor the spirit of evil by the practice of vice. They are thus cast out both from heaven and hell.—Ed.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.