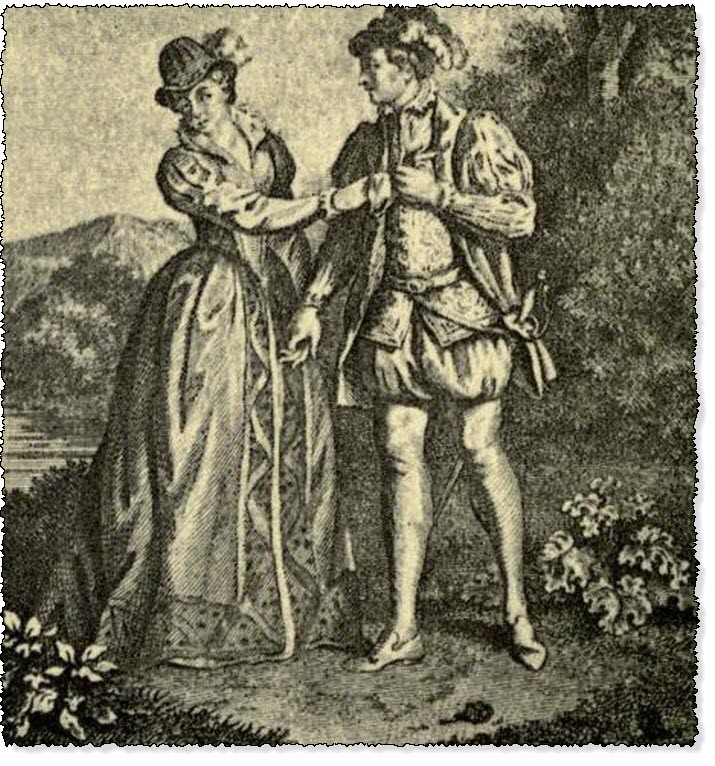

the English Lord Seizing The Lady's Glove

The Heptameron - Day 6 - Tale 57 - the English Lord Seizing The Lady's Glove

Summary of the Seventh Tale Told on the Sixth of the Heptameron

Tale 57 of the Heptameron

King Louis the Eleventh (1) sent the Lord de Montmorency to England as his ambassador, and so welcome was the latter in that country that the King and all the Princes greatly esteemed and loved him, and even made divers of their private affairs known to him in order to have his counsel upon them.

One day, at a banquet that the King gave to him, he was seated beside a lord (2) of high lineage, who had on his doublet a little glove, such as women wear, fastened with hooks of gold and so adorned upon the finger-seams with diamonds, rubies, emeralds and pearls, that it was indeed a glove of great price.

The Lord de Montmorency looked at it so often that the English lord perceived he was minded to inquire why it was so choicely ordered; so, deeming its story to be greatly to his own honour, he thus began—

"I can see that you think it strange I should have so magnificently arrayed a simple glove, and on my part I am still more ready to tell you the reason, for I deem you an honest gentleman and one who knows what manner of passion love is, so that if I did well in the matter you will praise me for it, and if not, make excuse for me, knowing that every honourable heart must obey the behests of love. You must know, then, that I have all my life long loved a lady whom I love still, and shall love even when I am dead, but, as my heart was bolder to fix itself worthily than were my lips to speak, I remained for seven years without venturing to make her any sign, through fear that, if she perceived the truth, I should lose the opportunities I had of often being in her company; and this I dreaded more than death. However, one day, while I was observing her in a meadow, a great throbbing of the heart came upon me, so that I lost all colour and control of feature. Perceiving this, she asked me what the matter was, and I told her that I felt an intolerable pain of the heart. She, believing it to be caused by a different sickness than love, showed herself pitiful towards me, which prompted me to beg her to lay her hand upon my heart and see how it was beating. This, more from charity than from any other affection, she did, and while I held her gloved hand against my heart, it began to beat and strain in such wise, that she felt that I was speaking the truth. Then I pressed her hand to my breast, saying—

"'Alas, madam, receive the heart which would fain break forth from my breast to leap into the hand of her from whom I look for indulgence, life and pity, and which now constrains me to make known to you the love that I have so long concealed, for neither my heart nor I can now control this potent God.'

"When she heard those words, she deemed them very strange. She wished to withdraw her hand, but I held it fast, and the glove remained in her cruel hand's place; and having neither before nor since had any more intimate favour from her, I have fastened this glove upon my heart as the best plaster I could give it. And I have adorned it with the richest rings I have, though the glove itself is wealth that I would not exchange for the kingdom of England, for I deem no happiness on earth so great as to feel it on my breast."

The Lord de Montmorency, who would have rather had a lady's hand than her glove, praised his very honourable behaviour, telling him that he was the truest lover he had ever known, and was worthy of better treatment, since he set so much value upon so slight a thing; though perchance, if he had obtained aught better than the glove, the greatness of his love might have made him die of joy. With this the English lord agreed, not suspecting that the Lord de Montmorency was mocking him. (3)

"If all men were so honourable as this one, the ladies might well trust them, since the cost would be merely a glove."

"I knew the Lord de Montmorency well," said Geburon, "and I am sure that he would not have cared to fare after the English fashion. Had he been contented with so little, he would not have been so successful in love as he was, for the old song says—

'Of a cowardly lover No good is e'er heard.'"

"You may be sure," said Saffredent, "that the poor lady withdrew her hand with all speed, when she felt the beating of his heart, because she thought that he was about to die, and people say that there is nothing women loathe more than to touch dead bodies." (4)

"If you had spent as much time in hospitals as in taverns," said Ennasuite, "you would not speak in that way, for you would have seen women shrouding dead bodies, which men, bold as they are, often fear to touch."

Heptameron Story 57

"It is true," said Saffredent, "that there is none upon whom penance has been laid but does the opposite of that wherein he formerly had delight, like a lady I once saw in a notable house, who, to atone for her delight in kissing one she loved, was found at four o'clock in the morning kissing the corpse of a gentleman who had been killed the day before, and whom she had never liked more than any other. Then every one knew that this was a penance for past delights. But as all the good deeds done by women are judged ill by men, I am of opinion that, dead or alive, there should be no kissing except after the fashion that God commands."

"For my part," said Hircan, "I care so little about kissing women, except my own wife, that I will assent to any law you please, yet I pity the young folk whom you deprive of this trifling happiness, thus annulling the command of St. Paul, who bids us kiss in osculo sancto." (5)

"If St. Paul had been such a man as you are," said Nomerfide, "we should indeed have required proof of the Spirit of God that spoke in him."

"In the end," said Geburon, "you will doubt Holy Scripture rather than give up one of your petty affectations."

"God forbid," said Oisille, "that we should doubt Holy Scripture, but we put small faith in your lies. There is no woman but knows what her belief should be, namely, never to doubt the Word of God or believe the word of man."

"Yet," said Simontauit, "I believe that there are more men deceived by women than [women] by men. The slenderness of women's love towards us keeps them from believing our truths, whilst our exceeding love towards them makes us trust so completely in their falsehoods, that we are deceived before we suspect such a thing to be possible."

"Methinks," said Parlamente, "you have been hearing some fool complain of being duped by a wanton woman, for your words carry but little weight, and need the support of an example. If, therefore, you know of one, I give you my place that you may tell it to us. I do not say that we are bound to believe you on your mere word, but it will assuredly not make our ears tingle to hear you speak ill of us, since we know what is the truth."

"Well, since it is for me to speak," said Dagoucin, "'tis I who will tell you the tale."

Footnotes:

- Some of the MS. say Louis XII., but we cannot find that either the eleventh or twelfth Louis sent any Montmorency as ambassador to England. Ripault-Desormeaux states, however, in his history of this famous French family, that William de Montmorency, who, after fighting in Italy under Charles VIII. and Louis XII., became, governor of the Orléanais and chevalier d'honneur to Louise of Savoy was one of the signatories of the treaty concluded with Henry VIII. of England, after the-battle of Pavia in 1525. We know that Louise, as Regent of France, at that time sent John Brinon and John Joachim de Passano as ambassadors to England, and possibly William de Montmorency accompanied them, since Desormeaux expressly states that he guaranteed the loyal observance of the treaty then negotiated. William was the father of Anne, the famous Constable of France, and died May 24, 1531. "Geburon," in the dialogue following the above tale, mentions that he had well known the Montmorency referred to, and speaks of him as of a person dead and gone. It is therefore scarcely likely that Queen Margaret alludes to Francis de Montmorency, Lord of La Rochepot, who was only sent on a mission to England in 1546, and survived her by many years.—L. and Ed.

- The French word is Millor (Milord) and this is probably one of the earliest instances of its employment to designate a member of the English aristocracy. In such of the Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles in which English nobles figure, the latter are invariably called seigneurs or chevaliers, and addressed as Monseigneur, Later on, when Brantôme wrote, the term un milord anglais had become quite common, and he frequently makes use of it in his various works. English critics have often sneered at modern French writers for employing the expression, but it will be seen from this that they have simply followed a very old tradition.—Ed.

- Alluding to this story, Brantôme writes as follows in his Dames Galantes: "You have that English Milord in the Hundred Tales of the Queen of Navarre, who wore his mistress's glove at his side, beautifully adorned. I myself have known many gentlemen who, before wearing their silken hose, would beg their ladies and mistresses to try them on and wear them for some eight or ten days, rather more than less, and who would then themselves wear them in extreme veneration and contentment, both of mind and body."— Lalanne's OEuvres de Brantôme, vol. ix. p. 309.—L.

- Most of this sentence, deficient in our MS., is taken from MS. No. 1520.—L.

- Romans xvi. 16; 1 Corinthians xvi. 20; 2 Corinthians xiii. 12; I Thessalonians v. 26. Also 1 Peter v. 14.—M.

Online Edition of the Heptameron

This is the Heptameron of Marguerite de Navarre

Other Sites: CruikshankArt.com · Dante's Inferno · Book-Lover.com · Canterbury Tales ·

This site is created by the Heptameron Information Society.